#NoMoreSilence no laughing matter

JAMES DUPRAJ

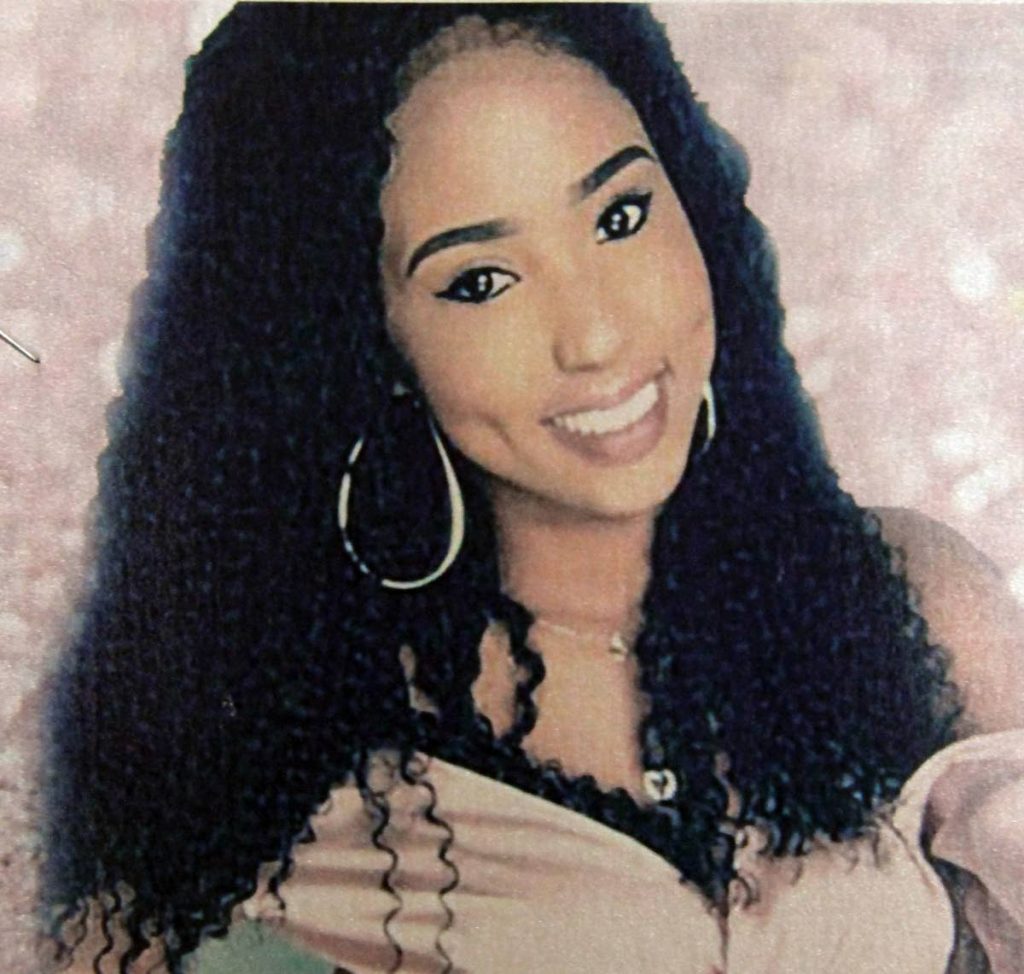

Rhea-Simone Auguste, better known by her social media persona “Simmy the Trini” (@SimmyTheTrini across social media), knows of the power of comedy to unlock dark experiences. With a background in journalism and marketing and communications, Auguste recently decided to try her hand at stand-up comedy, not knowing the responses she would garner.

“A lot of people had gotten to know my funny side on social media – in the TT Women’s Forum and on Facebook. I had a few funny posts go viral locally,” she says of the support and motivation that drove her to announce her first stand-up show in June of this year.

That first show sold out, as did her two subsequent performances.

As the comedienne says, “Stand-up is a beautiful platform for addressing social issues with a touch of humour.

People are more receptive to listening and understanding when the information presented is funny,” she reasons. But it must also be noted that even the funniest comediennes stand for very serious social issues and causes.

Last Sunday the nation was rocked with news of yet another slain woman. The victim was Samantha Isaacs, a young mother who was murdered at the hands of an estranged ex-boyfriend.

While Auguste is alive to tell her tale, Samantha’s story hit close to home.

As she shares, in her early 20s she too struggled to abandon an abusive relationship.

“That relationship ended with my front right tooth broken under the gum line, my lip split, and my right eye swollen,” she recalls grimly.

“Had a neighbour not intervened when I screamed out for help, I might not be here today.”

Samantha’s murder has triggered many such memories and experiences for women in TT – women who have been shamed into silence, or are too fearful for the lives of their children, families, and themselves to ask for help and redress.

Jhanah Haynes-Mark, clinical psychologist at Central Psychological Services (centralpsychologicalservices.wordpress.com, a clinic with a focus on creating safe psychological spaces for those in the LGBTQI community), has been counselling in Trinidad for almost a decade and has worked with many women – and some men – who have experienced intimate partner violence. She says, “There are many barriers for someone who is trying to get out of an abusive relationship. The first barrier is usually embarrassment. Secondly, the cycle of abuse keeps victims thinking that this last time will be the last time.”

However, Haynes-Mark believes the greatest barrier to women who wish to leave their abusive relationships is the lack of available resources. Controlling relationships take away a person’s sense of independence, which includes financial independence. “Extricating oneself from that type of situation safely is a complicated, multi-faceted affair,” says Haynes-Mark of the many moving parts that may keep battered people bound to abusive partners.

“Every time I see a domestic violence death, I always think ‘that could have been me’ but would just silently thank God for getting me out. But silence is a powerful thing,” Auguste admonishes the silence many women are forced into.

“In a domestic violence situation, you lose your voice,” she continues of this silence. “You walk on eggshells, afraid to say anything to offend your abuser. You might choose not to tell others because of the fear of what they would think of you. And even when you escape it, you may have to keep quiet to preserve the illusion that everything is fine, because again, there is a stigma attached to domestic violence survivors.” She adds that oftentimes, people victims of abuse, and even murder victims, as has been the case for Samantha Isaacs.

Social media posts alighted that perhaps it was Samantha’s own doing that led to her murder – reasons ranged from withholding her child from an abusive ex-boyfriend, or to the fact that she was a “red woman”.

It is this nefarious silence that Auguste hopes to combat. Inspired by Samantha’s story, she created the #NoMoreSilence hashtag and Facebook page. “Speaking out with #NoMoreSilence was my way of sharing and encouraging other women to share openly or anonymously through my inbox in an effort to show that there are a lot of us carrying this secret,” she says. “The hope was to spark the necessary dialogue to encourage both men and women in abusive relationships to get out as well as look at resources available.”

However, Haynes-Mark believes it is this lack of accessibility to resources for many of our nation’s abused that continue cycles of abuse. She says, “The victims of domestic violence and gender-based violence in TT need a system which facilitates professional support and guidance in navigating the delicate process of removing themselves from their abusive situation and moving on to a more stable, secure life. At a time when you are so vulnerable that you feel completely lost I think the biggest barrier to people getting the best possible help is not having someone guide them when they most need it.”

In fact, through her #NoMoreSilence campaign, Auguste has made contact with many survivors who shared their stories with her, and whom she has provided guidance to resources such as the Organisation for Abused and Battered Individuals (OABI).

#NoMoreSilence started with breaking the silence on her own experiences of abuse, but Auguste says it was still intimidating to share publicly even after a decade, highlighting how ingrained cultures of erasure and silence are in our society.

After sharing her original post in the TT Women’s Forum, within an hour she had gotten four private messages of women’s experiences of abuse. As the day progressed, the messages kept coming in. At one point, she had to take a day off social media as her inbox kept being filled with personal accounts of trauma.

“A lot of women were happy to share under the condition of anonymity but the stories were so painful and scary and angering that I had to take a step back. I’m not a therapist and I’m not equipped to intervene or help but I can motivate and follow up and keep reminding them that it is hard to leave but there is a better life waiting for them.”

Haynes-Mark agrees that public advocates such as Auguste must practice self-care in their quest to help survivors. “This work is exhausting, frustrating, often thankless, and can be very traumatising,” she echoes Auguste’s overwhelmed feeling. “It is imperative that those who are leading the movement educate themselves and those around them about available resources and options for people in need. As they are making themselves visible it is very likely they will be first to hear an abuse victim’s story. The more accurate their information, the better they can guide those who come for help.”

She also encourages activists and advocates to seek mental health assistance if necessary, as well as knowing when to step back and take a breath to recharge.

While social media has provided safe havens for many women and men to share stories of abuse (such as last year’s regional #lifeinleggings campaign and the recent international #MeToo campaign for women who have fallen victim to sexual abuse), Haynes-Mark also notes that sharing in therapy sessions or support groups may be preferred by survivors who have not yet fully worked through their trauma.

“Most times when the story is shared publicly, the backlash from members of the wider society can be very harmful. In the case of past abuse, it is usually better for someone to start by telling his or her story in a non-judgmental forum. If the abuse is ongoing, there needs to be some form of safety plan in place, because in leaving an abusive situation the victim’s safety should be paramount, and seeking help can be even more dangerous if there is no way to escape an abusive partner,” she says, adding that the onus is also on friends, family and loved ones of the abused to act as a buffer between them and an abusive ex.

Auguste also has words of advice for survivors or those still in abusive relationships. She says, “You are only alone if you don’t reach out to others. From my experience, healing started when I fought the shame to tell my friends and family what was going on.

“Having a healthy support system of friends and family helps and if you don’t have that, now you have a supportive online community.”

To connect with Rhea-Simone Auguste and other survivors of domestic violence, you can visit the “#NoMoreSilence” page on Facebook.

Comments

"#NoMoreSilence no laughing matter"