Kwynn maps the Caribbean

Kwynn Johnson carefully unrolls a section of her massive panoramic drawing, Place as Palimpsest, at her Maraval studio space.

The room is no match for the dimensions of the work.

The artwork, tidy when scrolled, is 43 inches high and 30 feet long, there are few spaces available for a working artist that can accommodate the canvas when it’s unrolled and to be honest, it also takes a fair bit of effort to take it all in as a viewer.

Johnson adds colour to the work, created in delicate but detailed graphite on the creamy canvas substrate.

She’s working from the top of a small section of the work, the length what can be comfortably unrolled on her worktable then draped down to benches and chairs pressed into service to support it.

She gently daubs blue watercolour paint on the pristine surface, massaging it delicately into the cloth and then stepping back to watch it soak into the cloth.

Place at Palimpsest is structured like the cross-section of an architectural dig, the layers of history imagined as scenarios, objects, fragments and the detritus of human existence suspended as they might be found in soil.

But here they hang in an imagined memory, a restructuring of the narrative of Haiti as seen in an artist’s rendering of generations of triumph, pain and patient sufferance buried beneath today’s surfaces, layer upon layer of human experience and effort illustrated with a sympathetic and perhaps anguished eye.

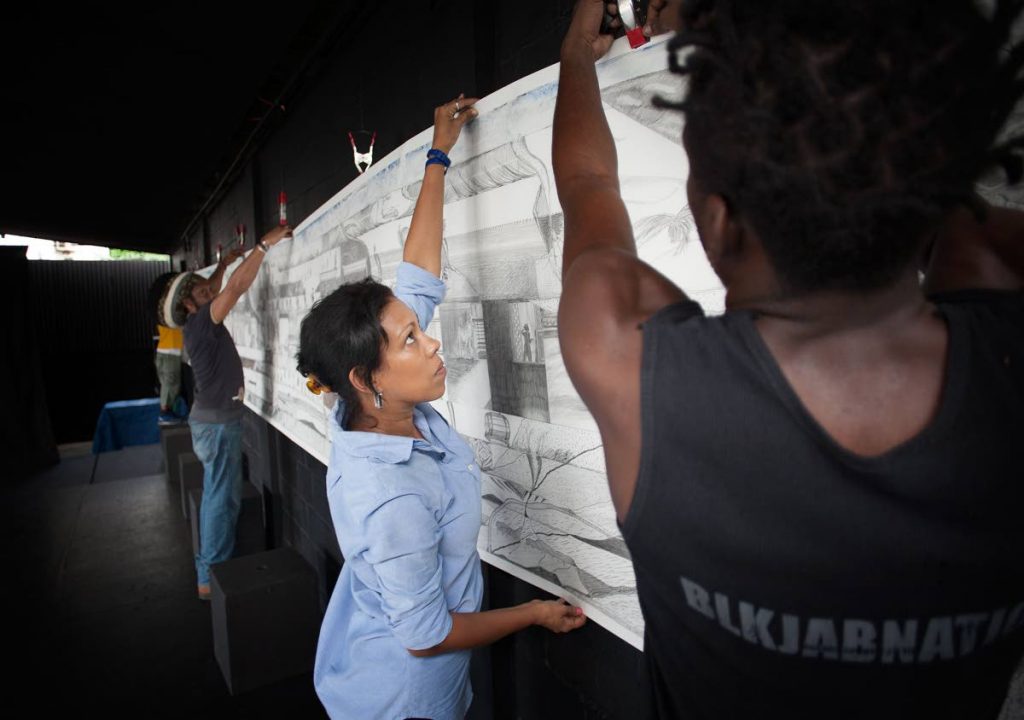

Place as Palimpsest has become a well-travelled work since it was first unveiled, or more appropriately, unscrolled at Bocas Lit Fest in 2017.

It was installed at The Big Black Box soon afterwards, the hanging remaining in place as a backdrop to the rehearsals and creative activity in the space.

It would be the second place where conversations about the work would add to Johnson’s consideration of the work.

At the Bocas showing, the editor of Caribbean Quarterly, Dr Kimberly Robinson-Walcott asked Johnson to share the work in the publication. Reproductions of sections of the art appeared in the June-September 2017 edition with a framing text by the artist.

Johnson would mostly hear about the Big Black Box responses second-hand from Wendell Manwarren, who told her that dancers and performers on break during rehearsal would just stand in front of the work, considering it and discussing it.

Johnson would present a paper on present a paper on the work and her efforts to capture in her art the idea of Cultural Geography at The West Indian Literature Conference in St Augustine later in 2017.

“But you know UWI people,” she said with a rueful smile, “nobody says anything.”

She’d get a more spirited response at the Biennial Rex Nettleford Arts Conference in Jamaica.

“Jamaicans are so vocal and articulate, they would come up to me to talk about it, lecturers and the students.”

“You don't want cheerleaders; you want conversations.”

Sometimes those conversations would take a strange turn.

At the fifth showing of the work in 2018 at the UWI Seismic Research Centre in St Augustine, Professor Richard Robertson, a vulcanologist from St Vincent assessed the work with the artist in geological terms.

“He could see the outcroppings,” Johnson recalled.

It wouldn’t be the only time that the work would be assessed from the very specific perspective of its viewer.

At the Haitian Studies Association Conference, Université Quisqueya, in Port au Prince, Johnson had what she described as an excellent conversation with Martin Munroe, an accomplished Haitian studies scholar.

“He asked me about how I incorporated the first people and their (found) shards as part of the palimpsest.”

Partly by design and intent and partly through the engagements that the commanding artwork has had over the last two years, it has become more of what it was designed to be, a record, erased and redrawn through experience that reveals its past in barely visible traces.

With her decision to add colour to the work, the artist is now applying a practical and technical dimension to her multi-layered imagining of Haiti’s history.

“It’s taken me two years to think about how colour would work on it,” Johnson said.

The watercolours she is adding to the work are just blue and yellow, the colours of sky and earth, but where they meet, they create a vivid green that sparkles on the canvas.

This preliminary painting in the studio is an assaying of how she will proceed after the work is hung at Softbox gallery.

There, she will continue adding colour to the work during its showing.

“I'm painting on it because it’s actually going to be up.”

“An artist wants to work on art the way it's going to be viewed, and this is an opportunity to make decisions in a technical sense, engaging it as a work, not with romance and emotion.”

“It's an opportunity for me to look at it again in a space, to examine how the colour works.”

The work travels south in October for the University of Guyana’s hosting of the West Indian Literature Conference, where Johnson will present a paper and place the artwork, as she describes it, “in conversation with Guyana and their concerns about environment.”

“When you look at an artist's body of work at the end of their career, often times, it's one story they've told thematically, in which each exhibition was one chapter.”

“I'm now beginning to connect those dots, with the Blue exhibition in ’97, which was about Buccoo Reef, considering ecology with Black Gold (in 2010), I'm seeing a thematic concern about the land, the landscape and cultural geography running as the theme through the work and the exhibitions.”

“Professor (Patricia) Mohammed raised that when I was her PhD student nine years ago. You don't think about it really, but she examined my MA work and place and meaning are definitely themes that run through my work.”

“I think it all really becomes one story, thematically.”

Comments

"Kwynn maps the Caribbean"