The making of Raymond

Malcolm Gladwell put a number to the time it takes to become an expert at doing anything. Beyond the notion that practice makes perfect, he crystallised the workload at 10,000 hours, the time it takes to truly know something.

Between 1979 and 1993, I had sight of what that really means when it comes to theatre in TT, as I watched a group of young people begin their careers with Cinderama at the Little Carib Theatre, a Christmas pantomime put on by Helen Camps, a show that began sowing the seeds of a new generation of players, writers, musicians and production staff.

I’ll freely admit now that I didn’t notice Raymond Choo Kong at first. He was distinctly older than his peers. Quieter. Less inclined to engage, given to considering and evaluating.

The evidence was there before me this weekend as I went through close to a hundred contact sheets and even more negatives looking for photographs of him.

There were just two frames from Cinderama of him singing, his spotlight moment after underplaying the mute role of King Dumb for almost 70 minutes.

There are only two frames of him from the portrait session for The Fantasticks, a staging of the musical by Judy Stone for the Hotel Normandie Dinner Theatre series.

It was an age of metered frames, and each photo came with a cost in materials and time, but really, TWO frames?

The only explanation is that I was underestimating this quiet little Chinese man, expecting him to fade away.

Many others did. I look at their photos now and can’t remember who they are. Their time in local theatre was short.

When Camps left the Little Carib Theatre, in ugly circumstances, to start the Trinidad Tent Theatre under a tent on a vacant lot on Stanmore Avenue, most of the cast of Cinderama and its Carnival successor, King Jab Jab, joined her.

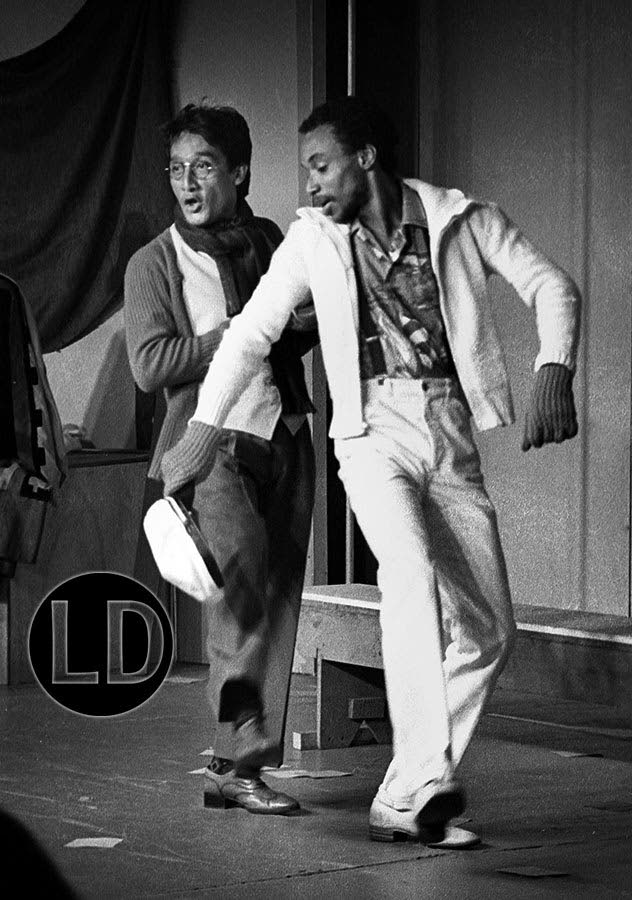

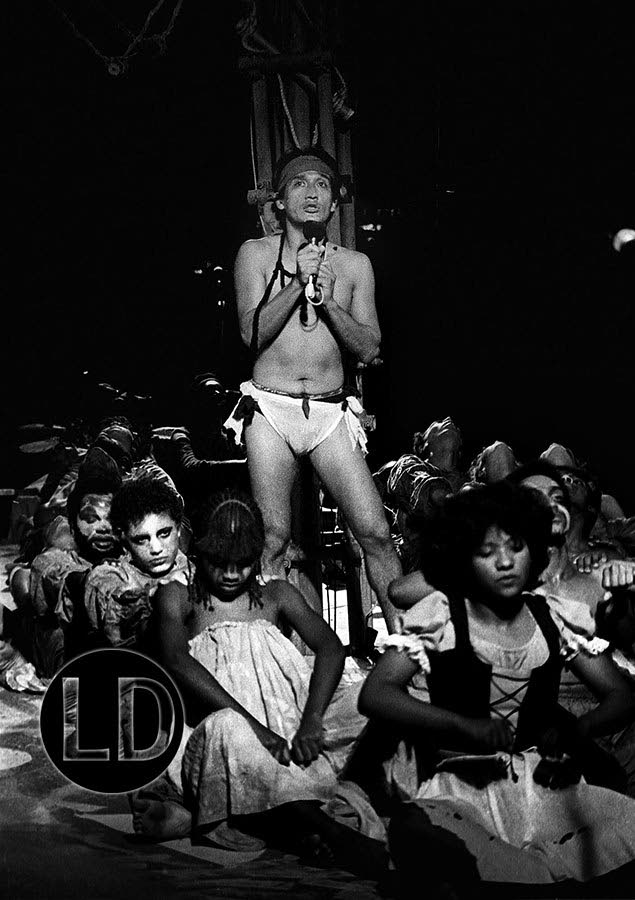

For the next production, Choo Kong took centre stage as Vetsin in a new original work, Ad, a lightly cynical work that championed a more natural life with original songs and a score by Roger Israel. The piece would later be reworked and restaged as Rampanalgas Sunrise, with Choo Kong again in the lead.

He sang. He danced. He acted. Most compellingly and mortifyingly, he wore a diaper for the first third of that show, as Vetsin’s character journey was reflected by increasingly more sophisticated clothing.

He was, in short, a trouper. An actor who was all about the show. A singer who was all about the song, and, eventually, a producer who was all about the success of the production.

As I sifted through the envelopes full of yellowing photographic paper, I was stunned to realise that he’d taken the part of a Midnight Robber in the Tent Theatre Carnival production, Go To Hell. A Midnight Robber. I had not remembered that at all.

After the theatre got notice to move from Stanmore Avenue, he would find his most robust theatrical challenge yet with a production of Bent after the tent was pitched at The Hollows, the once bowl-shaped bit of land just west of the zoo that’s being filled and paved now as part of its expansion.

In Martin Sherman’s play about Nazi persecution of homosexuals, Raymond Choo Kong finally found himself, I think.

He was an older man among teenagers, a closeted gay man who found himself among boys flaunting their sexuality fearlessly, and an actor coming to grips with his powers. You could see him being shaped by that experience.

Within a few months, a tree would fall on the tent and the struggling group would never fully recover from that.

I’d moved on from theatre generally, though I would return for a few years to work with The Baggasse Company, while Choo Kong began staging comedies in a careful pattern, feeling out the market, and gauging the possibilities for his own productions.

We would meet again on M.Butterfly, a staging of the David Henry Hwang play that starred Choo Kong as Song Liling.

I’d do him a great injustice on this project, getting myself into a rage over his demands for increased pay on the cusp of the play’s opening. In a fury, I cut up his lobby portrait on the final night, put the chips in an envelope and gave it to a member of the company to pass on to him after the performance.

I was busy quaffing tea for someone else's fever, and it was a mean and cowardly thing to do.

M.Butterfly was the last Baggasse production I was fully invested in. I drifted away from the group after that and fully intended to leave theatre behind at that point. But Anthony Seyjagat would have none of it.

The Little Carib Theatre was closed for repairs that would take years. The Central Bank Auditorium ended theatrical productions on its stage. Queen’s Hall was booked for years.

Raymond Choo Kong had opened The Space Theatre, a tiny space in Bretton Hall with a bar. Seyjagat, who was working at The Space, wanted me to take a meeting with Choo Kong, who was rightfully doubtful. I think Seyjagat worked on both of us to make it happen.

I worked on a few shows, doing portraits for a Diva production, the Chinese Arts Group’s Thunderstorm, the farces Natalie Needs Her Nightie, featuring Renee Castle, Ding Dong Dead and Murder, Anyone.

I didn’t care for it much. Choo Kong didn’t care whether the show itself was photographed. He wanted staged photos and portraits for publicity.

Seyjagat died by suicide in the midst of all this. At his seven days, I talked about how hard he had worked to bring me back into theatre. Choo Kong reached out to me in the sombre circle of remembrance and we hugged.

I was really done after a few more productions. I’d never work in theatre like that again.

I knew Raymond, but Anthony had been a relentless charmer and more than that, was an actual friend.

Although everyone loved Raymond, it turns out I actually didn’t like him very much at all.

I’ve often wondered why that was. We never quarrelled. He always greeted me warmly. Why was it so easy to be nasty to him that night at the Central Bank?

Some of it was an age difference. Nine years is a big distance when you meet someone and you’re just out of your teens.

Some of it might have been our interests. To be a straight man in a gay sanctuary doesn’t mean being sidelined, but if you aren’t interested at all, there are things you don’t get invited to, sources of laughter you are forever unaware of. You find yourself in the thing, but not of the thing.

A bit of it might be what he chose to do with his talent. He was there when a template for working here was laid down, and while he took a lot of it forward quite successfully, he also set aside a lot, because he couldn’t make it fit and make money too.

We set off from the same shore, but ended up charting quite different courses.

He became a foundation for a very different kind of theatre, one that succeeded in shaping a form that was sustainable, and that’s an important legacy.

Leaving theatre as I did, I embraced the role of useful footnotes, referenced on occasions like this one.

Looking back over those hundreds of photographs, I find myself pleased with the record, with this way of remembering a remarkable and formative time in local theatre.

Raymond Choo Kong deserves to be understood in his entirety, not just as the funny man who charmed thousands, but as an artist who took the time to master his craft, explored it fully, then shared it with his peers.

Comments

"The making of Raymond"