Continuing the Codicil

RUEL JOHNSON

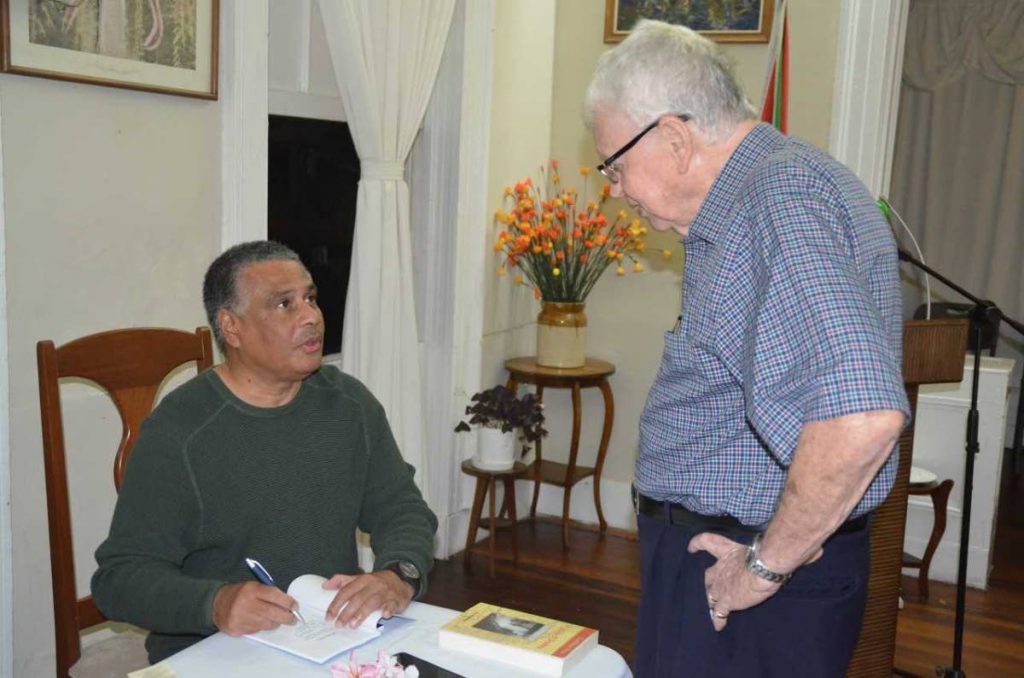

This is an edited version of Johnson’s address at the launch of TT journalist and poet Wesley Gibbings’ Passages, in Georgetown, Guyana.

“Schizophrenic, wrenched by two styles,

one a hack’s hire prose, I earn

my exile…”

That was the St Lucian poet Derek Walcott’s meditation upon his time spent as a journalist in TT in one of his better-known poems, Codicil. For those of us stricken with that most horrific of conditions, cacaothes scribendi, this schizophrenia is one that is easily recognisable. It is one that a young Wesley Gibbings would face in the late 1970s, his first collection of poetry already under his belt and with the “new world, naked” of independent, post-independence Trinidadian journalism open before him.

Where Walcott had a decade or so earlier chosen the primary path of poetry, Gibbings in the early 1980s chose the primary path of prose. It has been, obviously, not an unrewarding path. Today, he is one of the Caribbean’s most recognised and most decorated journalists, and an unparalleled leader when it comes to press rights and freedom of expression. There may be many descriptions for the work Wesley has done in his 40 years as a journalist – “hack’s hired prose” is not one of them.

Despite Walcott’s cynicism, for the person who is a poet at heart, journalism is perhaps the best possible exile, certainly better than the often arid, barren wasteland that is government policy. If poetry affords us a microscopic view of the essential human condition, journalism offers the often-necessary macroscopic perspective.

These presumably bifurcating paths, the two poles of the schizophrenia, are often in fact complementary, the pathos of the poetry informing, infecting the prose, the objectivity required of journalism tempering the at-times too passionate nature of poesis.

For example, let me read from a Q&A between Gibbings and young Trinidadian academic Amilcar Sanatan, where Gibbings addresses the continued “legitimacy,” as it were, of mainstream journalism:

“People are discerning,” says Gibbings, “and if they know that the source is not transparent they will know that the writer cannot be held to account. Mainstream media has professional standards and ethics guiding it, generally. I know the value of mainstream media through its relationship with audiences when crises occur. Who do people really turn to? We had the recent experiences of hurricanes.”

[Gibbings breaks into tears]

"It’s hard to talk… that is the source of my current state, the hurricanes.”

Gibbings breaks into tears. It is a startling, poetic thing, to encounter in a transcript of an interview between an academic and journalist, yet there it is, the poet’s pathos in as prosaic a topic as we can encounter.

In his poem Surviving the Storm, the final stanza reads:

I waited and waited till the storm had stopped

but the river flowed

and the beads I saw

were no longer tears

but balls of bitter glass

unbroken, unborn

unable to live and, therefore, to die

Herein we have a curious contrasting irony, the lachrymal vulnerability of the journalist Gibbings in the wake of a communal disaster in another country, compared with the crystallised emotion in the aftermath of a tempest-tost personal relationship as captured by the poet Gibbings.

Much of Passages is made up of such vignettes of interpersonal relationships, a celebration and lamentation of transient romantic encounters, impressionistic portrayals of women, or rather of their relationship to the poet.

It is perhaps here that the journalistic inclination to protect source results in one of the few weaknesses in the collection. Whereas much of the portrayal of intimacy in the collection owes a great debt to Walcott and Neruda, there is an actual and imagistic anonymity that restrains some of the best poems just short of the full power of intimate portraiture that exists at their core.

The journalism presents itself as a strength in other poems, however, particularly in informing his treatment of the subject of communal violence, in Trinidad, in Haiti and in Guyana, as well as his treatment of more mundane, spatial experiences.

No matter how illustrious, how worthy the journalism, the poetry remains a necessary, an inevitable and irreplaceable codicil to even the most well-earned of exiles, and clearly – as well-earned as Gibbings’ exile has been and continues to be – his dual opus continues to be created, even when he, as in his poem The Time has Come, threatens to sideline the poetry:

I am going to clear the room

Sweep it clean

On this side goes Neruda

And then Vallejo

On the other

Carter and Derek

Under the old, irrelevant

Metal desk is an empty

Ink cartridge

Not one drop to spare

Clearly, that old ink cartridge was not that empty – indeed it appears to have had at least an entire collection’s worth of poetry, the writer’s fifth, inside it.

Ultimately, as the name suggests, Passages is a significant, later chapter in the companion diary of a seasoned traveller. Despite, his youthful looks and energy, Gibbings been about lang lang. This is why, inevitably, quite a few of his poems treat with the inevitable issue of mortality

For Gibbings, the physical experience of ageing, the recognition of mortality, the familiarity with the dead, the resignation to fate is not dissimilar, as we see in several poems, including these lines from Because we know:

We grow old and fat around the waist

our lives leaking like old galvanise tanks

in the harsh Mayaro sun

We know it’s time to know

what grows on sand and concrete –

music we once knew

but no one hears on the radio –

Barry White and Marvin Gaye

And Kitchener and Andre

have all died, you see

It is therefore not unsurprising that we find in this collection a meditation in tribute to Dylan Thomas’s Do Not Go Gently…, one that, like the other poems on ageing in the collection, while good, still feel too “early,” too climactic considering the general energy and thrust of the rest of the collection, a bit of premature maturation, if you will.

All things considered, for me the central lesson in Passages, one that resounds both as reader of poetry and poet-journalist, is that 40 years ago, two roads diverged in a verdant wood and Wesley Gibbings realised what few of us do, that he could take both, and that has brought us this solid, valuable work of poetry, this continuing codicil.

Ruel Johnson is a Guyanese writer

Comments

"Continuing the Codicil"