Margaret Busby on wokeness, diversity and what it takes to make it in publishing

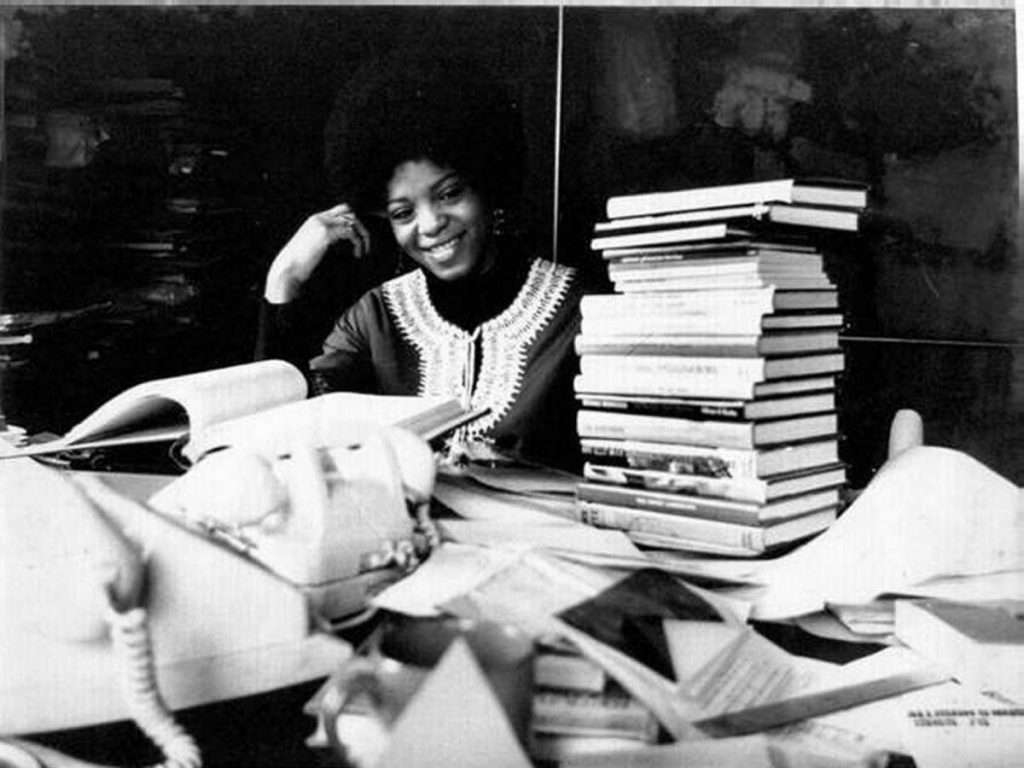

The youngest publisher as well as the first black (Ghanaian-born) woman publisher in the UK: in 20 years of publishing, writing, editing and broadcasting, Margaret Busby has given voice to hundreds of brilliant writers, ranging from the post-colonial brilliance of Trinidadian author CLR James to gonzo journalist Hunter S Thompson (of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas fame), and through her now famous Daughters of Africa anthologies, which brought 200 women writers into the mainstream.

Little wonder she has been showered with accolades, including a Commander of the Order of the British Empire and the Benson Medal from the Royal Society of Literature. Most recently, Busby was chair of the 2020 Booker Prize judges, one of the most prestigious in literature.

With our conversation continually interrupted by the sounds of tropical rain on galvanised roofs, Busby sat down with me virtually to break down exactly what makes such an extraordinary career, and to dig into the true meaning of diversity.

You’ve clearly been able to spot talent and edit incisively. Take us behind the scenes of a top-tier publishing meeting. What is that process like?

We were both so young (Busby and her business partner Clive Allison). We conceived the idea of starting our own publishing company at university, and found authors in very different ways from the usual. We first published a writer we met in a pub!

A friend of my husband met Sam Greenlee (author of The Spook Who Sat by the Door, the first novel Busby published) and because we were so small – there were just two of us – Clive Allison and I were doing everything. I wrote the cover, I made the blurb. It wasn’t a huge number of people. It was just a couple of young people – two or three of us.

Someone heard that books about animals were popular. So we said, let’s publish a book about animals! We ended up publishing a book about rats (laughs). We published books about songs to sing in the bath, which we printed on waterproof paper. We had to fight to get authors reviewed.

We had no official distribution in the early days. One of the ways we distributed our books is stopping people in the streets!

So often I go to festivals and there is this “them and us” mentality, and I don’t want that to be the case. It almost seems as though people are asking: what are “they” (the publishing and arts establishment) going to do for "us"? “We” are on the outside and “they” are on the inside. People think: somebody else is going to make us rich and famous.

But we can be on the other side (the side of the establishment). We (Allison & Busby) publish books because they are good books. We’re letting people into our hallowed halls. We should all be there to make it richer. We have to claim it – we have to be involved in everything. I always think of somebody like Toni Morrison (Nobel-prize winning author) – she was also a publishing editor. She was not saying, I am outside and somebody needs to let me in.

What are your thoughts on recent pushes for diversity in the arts and business world?

Writing is simply a question of doing what you believe in – and that may involve a lot of culture and literature from around the world.

I started so young – I wasn’t trying to fit into the conventions. We didn’t know what it meant not to do something.

We started by publishing three sheet paperbacks. As a publisher, we just wanted to do what wasn’t being done. It wasn’t a question of ticking boxes.

We published so many of CLR James’s books. I knew him as a family friend, but by then he was almost totally out of print. I brought his books back into print. There were things we did in that way. Somebody like George Lamming (the acclaimed Bajan novelist) – his book had been turned down by 40 publishers.

I was just doing what I wanted to do. We had that mix. A lot of people came to us precisely because of that reputation for being mavericks. You never knew what they were going to publish next and you knew it was going to be interesting. You get a mix of brilliant books. We published, among others, Ralph de Boissiere (the Trinidadian activist writer).

I could do another anthology tomorrow. Look at all these women of African descent who have been creating wonderful literature over the centuries. I made a point of this.

I think what is changed is that people are more aware. You wonder how long that is going to last. But diversity comes in all sorts of forms – it’s class and regional and style.

What do you think of ‘wokeness’?

I’m not sure who is saying it, and why. Am I woke?

The mainstream publishers are woke. One of the things that I heard in 2019 as I was travelling a lot around Britain, at each festival event there was this recurring scene where someone gave a talk, about "normal" books and "diverse" books. There was a sense of: “Look how good we’re being,” as they were about diversity. They’re saying: “Well, we’re woke.”

So what were you before and what will you be when the fad goes away?

One of the broadcast producers. for example. was doing a series and had to interview a Muslim writer – they postponed it because they’d had another Muslim woman the week before.

One of the women talks about a conversation with their editor. They didn’t want any more than three Africans in a certain period of time. To that extent there is still that feeling that the gatekeepers have that power. It’s just now they are “woke.”

I would get as many different people involved as possible. I want an intergenerational field. You want people choosing the books to read it. You don’t want there to be a monopoly. You want people to be involved. No one is doing you a favour.

How did you start writing jazz lyrics?

I’ve always been fascinated with lyrics and words. One of my cousins was called David Busby and David came to Ghana when he was about three or four. He was trying to teach my elder brother George, getting him to spell.

The first three words I was taught to spell were “necessary, fascinating and picturesque.” It began a fascination with poetry. It was just something I enjoyed doing. With my husband being a jazz musician, sometimes my lyrics got sung by singer friends. I love good jazz lyrics.

There was a piece by John Coltrane. There weren’t very many who recorded the theme. My friend Norma Winston, and another of my musician friends – Randy West – were those that did.

On judging the Booker: what percentage of the books do you have time to finish? What makes a good Booker judge?

All in all, we had to get through about 162 books. Most of them ended up being on the screen as PDFs. We had meetings every month. One of the points to remember about judging any prize: we are looking for a book that weighs exactly two stone (laughs).

But I love longlists and shortlists more than I focus on the winners.

What you don’t want with any prize is that any judge is exactly the same. You don’t want a result that is just boring. It’s about not keeping people out. Let’s all participate. Choosing the right judges? You choose whoever you think would make a good decision. It’s not a certain age. They may be 20, or 70, in London or in Trinidad.

What advice would you give for someone looking to break into the industry?

You have to be open to things changing, evolving. How have you personally changed and evolved? I am bolder now. Your family have aspirations, of course. You have to be able to tell them: "Actually, I’m going to be a publisher."

It takes a certain sort of courage. You don’t have a mortgage or dependants. You have the internet, you have things that make it easier – mentors. Ok, I was the first “xyz,” so people can ask me. They can ask my advice.

I’ve either got bolder or less bold. I was actually quite shy at first. Mix with people who aren’t like yourself. Just be open. Don’t be stuck in your views, your ways. Be open to people suggesting things. That’s my approach, in a way.

You could be an agent, for example. You have to work hard. Nobody is going to make huge sums of money in the early days. I would have earned more money going to work in the supermarket when I started at a publisher, which is how come I ended up working at the BBC part-time.

What does publishing mean: it means making something public! You can do that very easily. If you can photocopy something, you’re a publisher. You have a computer: you can work wherever you are.

Most people seem to think: "Oh, I can’t do that because I haven’t got a million pounds in a bank account." You start where you are.

Kiran Mathur Mohammed is an economist and co-founder of medl, an IDB lab-backed social impact health tech company. Share comments and feedback kmmpub@gmail.com for comments and feedback.

Comments

"Margaret Busby on wokeness, diversity and what it takes to make it in publishing"