This one is for Uncle LeRoy

Freedom. In 2021, the concept continues to be a volatile one.

The freedom to love who you choose, to believe or not in a higher force, to be socialist or democratic, to change your sex or identify with none at all, to disagree with public opinion, to travel from one country to another, or to wear your hair in canerows at work.

It felt like a cuff to my stomach when I heard the news.

I remembered how the four boys, Eintou’s grandchildren, walked into the room and Uncle LeRoy’s eyes sparkled. He immediately sat up, straightened his back and swung his legs over the edge of the bed.

He spoke to them in his blunt, often expletive-laden way, about freedom. Not just accepting someone else’s view of it, but creating their own version of liberty. He spoke to them about love, relationships, about work and creativity.

But most of all, he spoke to them about warriorhood, African identity and manliness. They listened, we all did, with the sense that this was a significant moment in all our lives.

My tears cascade, a puny reaction for a force of nature.

The pit in my stomach accuses me of being weak, warning that I should have a plan to continue his legacy. His eyes burn into me and I hear him say his typical, "Forget about all that s--t." As Ida, my grandmother, would say "Come, come, shake up yuhself, chile."

It is even harder when the warriors go. Somewhere in our soul, we believe they should not die. But the passing of a warrior reminds us that perhaps we depended on them too much. Perhaps we relied too much on their strength and valour to secure freedom for us all.

This year, the contradiction of Emancipation and social restrictions is stark.

The drum call and libation for the ancestors will be online because of an ongoing state of emergency. Celebrations will be limited to our homes. Maybe this is what the times require.

It is said that Marcus Garvey viewed Emancipation as a time of stocktaking and setting goals; maybe the passing of our cultural icons is their way of handing the responsibility of battle over to us.

It was 183 years ago when the British were forced to release generations of Africans from enforced bondage. By the time the legal enslavement of Africans was fully abolished Britain, France, the United States and other nations had profited significantly from the trade in enslaved Africans and the labour of their descendants in the Caribbean and the American south.

Some years ago, Prof Hilary Beckles described the act of Emancipation as "despicable" because it “was an act in which black peoples were finally defined by Parliament as property, and their enslavers deemed entitled to compensation for property loss.”

As the post-Emancipation decades unfolded, discriminatory laws in TT and across the Caribbean restricted the ability of Africans to own land or property, making it even more difficult to overcome impoverished circumstances. Colonialism, colour prejudice and other injustices would ensure that true freedom for the African remained, well, elusive.

Today, as regional institutions seek justice for Caribbean people, there is a vast body of scholarly work to support the case for reparations. They include Labour in the West Indies, written in 1939 by Nobel laureate Sir Arthur Lewis of St Lucia.

Long before the idea of reparations was proposed, Sir Arthur asserted that the “unpaid labour extracted by the British from the enslaved people of the Caribbean is a debt that must be repaid to their descendants.”

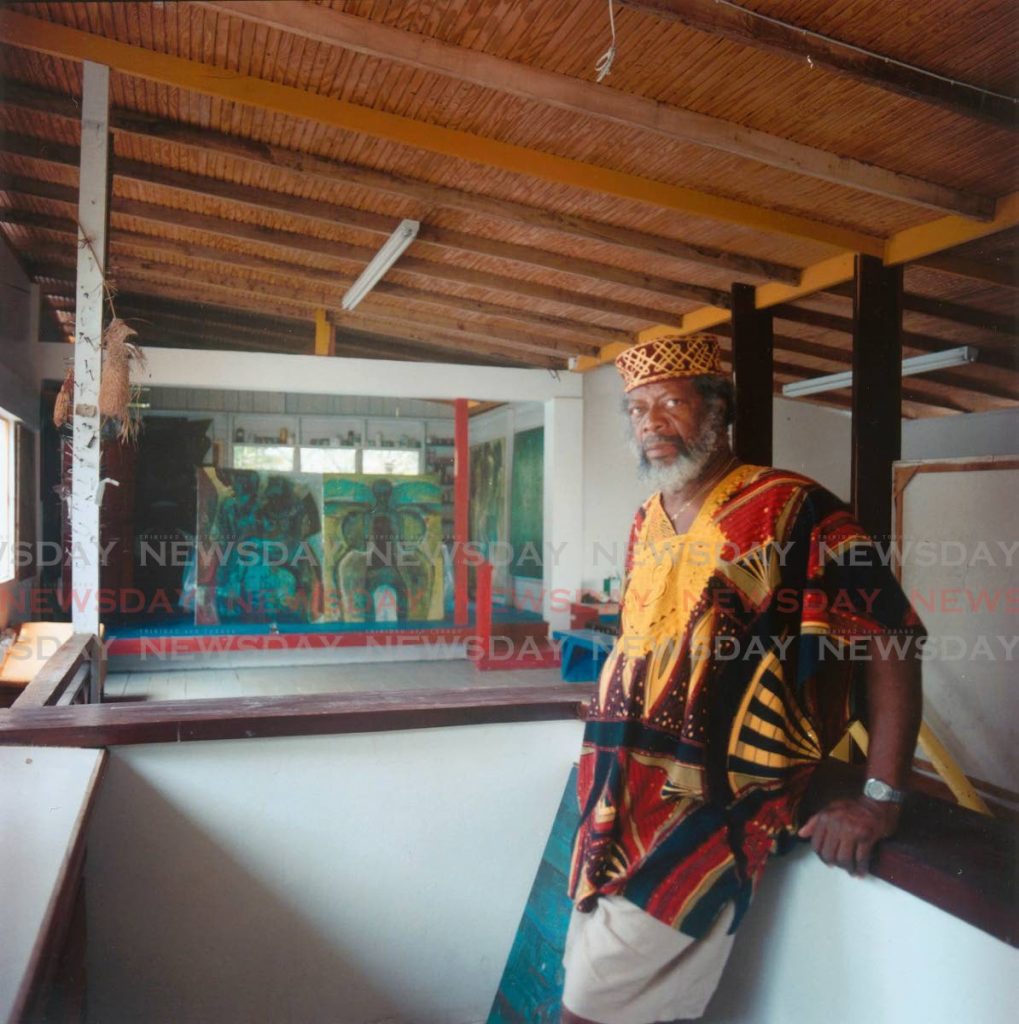

Uncle LeRoy was among that vanguard of artists who understood the significance of their work in attaining true freedom.

He affirmed African identity and spirituality, openly challenging historical prejudices about African culture. It was especially important for him to share these concepts with young people. But his voice was one of a few.

The other warriors are aging; they too are tired.

Globally, there is limited progress. The UN International Decade for People of African Descent is almost over, yet there is inadequate trade between Africa and the Caribbean, no direct flights, no forgiveness of debt (ask Haiti about this one). No apology.

Tjis year, 2021 also allows us the freedom to be vulnerable, lost. As the elders that I depend on transition, I hold them close by tapping into the spiritual energy we shared. Travel well, Uncle LeRoy. Stay close; I still need your help in my own quest for freedom.

Love and hugs as always.

D

Dara E Healy is a performance artist and founder of the Indigenous Creative Arts Network – ICAN.

Comments

"This one is for Uncle LeRoy"