William Burnley, enemy of emancipation

WILLIAM HARDIN BURNLEY, the wealthiest plantation owner in Trinidad, was one of the most vocal opponents in the journey towards emancipation.

African Emancipation Day, observed annually on August 1, celebrates the hard-won freedom of enslaved Africans in Trinidad and Tobago.

This pivotal moment in history came after years of resistance, struggle and abolitionist advocacy against the powerful forces, of the sugar plantation owners – led in this colony by Burnley, owner of the largest number of estates and the people who worked and suffered on them.

Burnley was born in New York in 1780 into a prosperous family, the son of a British merchant. He was educated in the United Kingdom at the prestigious Harrow School before relocating to Trinidad in 1798, just a year after the British took control of Trinidad from Spain.

It was here in Trinidad that Burnley found his new home, gradually becoming the most successful plantation owner in the nation and a powerful figure in local and West Indian history.

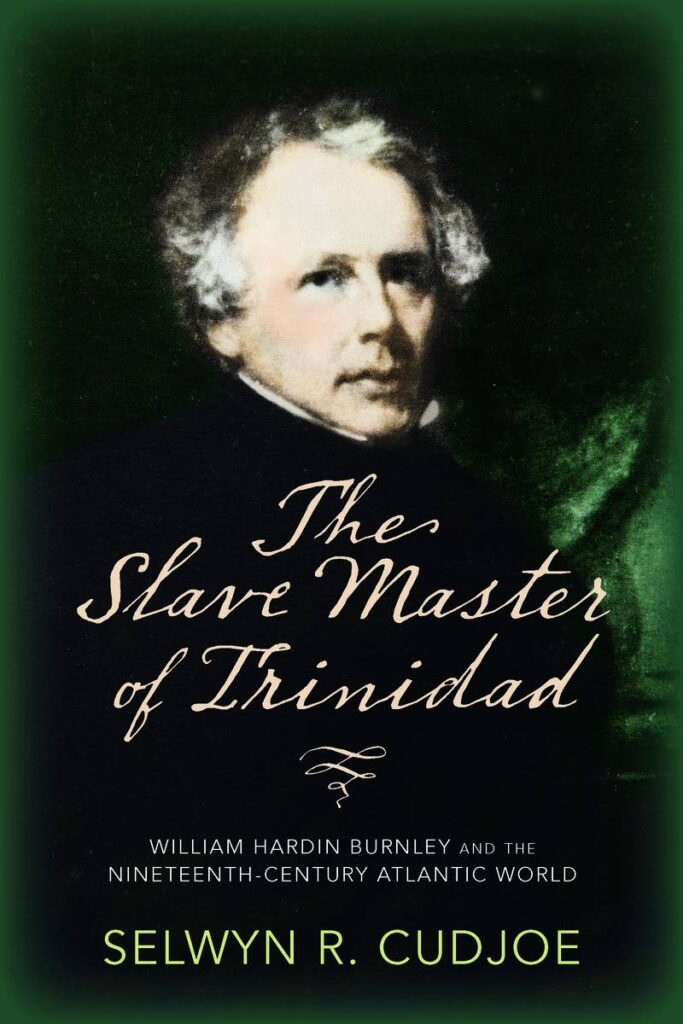

Prof Selwyn Cudjoe, author of The Slave Master of Trinidad: William Hardin Burnley and the Nineteenth-Century Atlantic World, said Burnley was instrumental in shaping local policy between 1810 and 1850.

Cudjoe says in his book: “During the first half of the nineteenth century, he was considered one of the most learned and influential men on the island and a prominent personality in the discussion of colonial affairs...

"During his time, he dominated the island's economic and political life..."

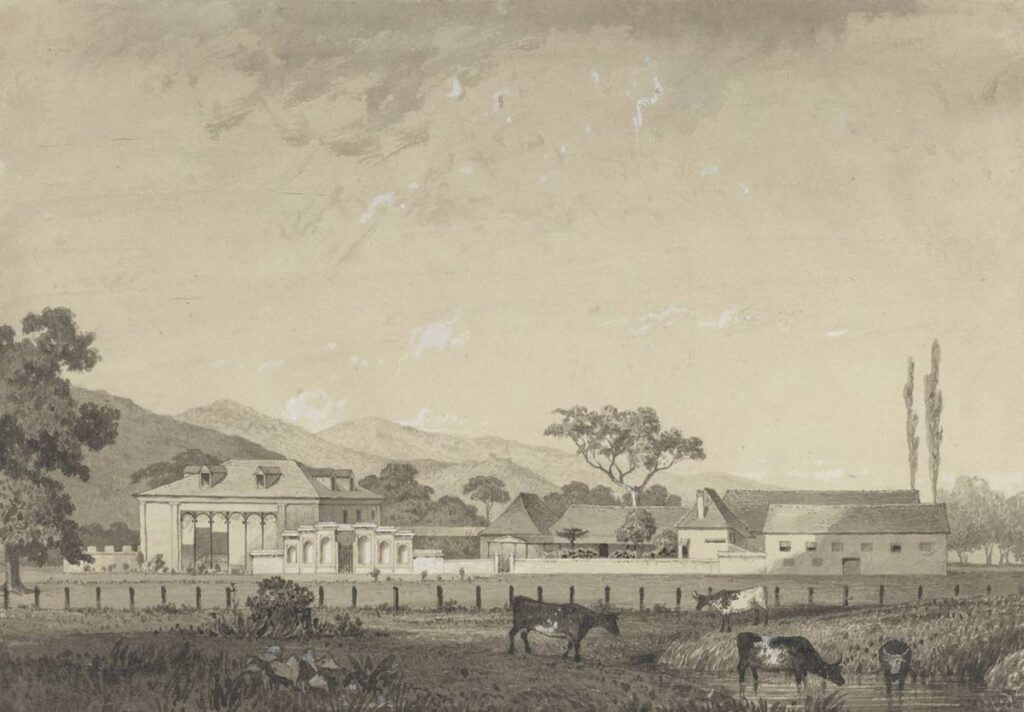

Burnley acquired vast amounts of wealth through slavery and the sugar industry. He owned 14 estates, of which the Orange Grove sugar estate in Tacarigua was the largest. Cudjoe says the estate measured 2,600 acres, worked by over 200 enslaved people. Cudjoe notes that Burnley owned approximately 1,500 enslaved people at the time of Emancipation.

At Orange Grove Burnley built a grand mansion, said to have 101 windows – even more than the home of the governor at St Ann’s – an impressive symbol of his wealth and status.

Burnley moved up in society, acquiring friendships and strategic positions in influential political spaces. He held the position of acting depositor-general, and he and his colleague Chief Justice George Smith were able to acquire numerous properties. Burnley made his fortune with this practice and is said to have been worth about half a million dollars through questionable means of acquiring land.

Deemed the “natural leader of the planters on the island,” according to Cudjoe, it was inevitable that Burnley became a member of the Council of Government (the name of the Legislative Council at the time), where he was a staunch lobbyist for the plantocracy (planter class).

His Orange Grove home became an important meeting place for Burnley and his fellow planters. Cudjoe says the estate was the place where “the action was taking place,” as the site where the planters met to develop and strategise against emancipation efforts in a bid to safeguard their financial and personal interests.

When Sir Thomas Fowell Buxton, British MP and a leader of the abolitionist movement, moved a motion to end slavery, the plantation owners were outraged, as the loss of enslaved labour would directly affect the profitability of the sugar industry.

Burnley was appointed the representative of the Trinidad plantocracy to the UK Parliament, and in 1832 he travelled to London to oppose the emancipation campaign, spreading anti-emancipation rhetoric and lobbying for the agendas of the planters he represented.

When Buxton proposed measures to prohibit the corporal punishment of female slaves and other reforms to improve the standard of living of the enslaved, Burnley and his planter colleagues were in complete disagreement.

Burnley believed enslaved Africans were ignorant “children” who required a very stiff hand to keep them under control, or else risk insubordination.

Prof Emerita Bridget Brereton, in a UWI lecture on emancipation, said planters meted out brutal punishments for resistance, conspiracy to rebel and poisoning, as they were afraid of being poisoned by enslaved obeahmen.

So the increased instances of resistance and revolt from the slaves at the time, such as the (Saint-Domingue) Haitian Revolution (1791–1804), the Tobago revolt of 1802, Barbados 1816, Demerara (Guyana) 1823, and Jamaica 1831, further exacerbated the planters' anxiety and fuelled their desperate attempts to thwart any initiatives to benefit the slaves.

However, the plantocracy ultimately lost when slavery was abolished: Parliament passed the Act of Emancipation in 1833, and it went into effect on August 1,1834.

Brereton says the “prime mover” of the drive towards Emancipation was the enslaved themselves, through their resistance and revolution. Among other factors, the Crown believed the trade too dangerous to continue and not as economically viable as at its peak.

However, even after the Emancipation Act came into effect, Burnley remained active, continuing to oversee the system of apprenticeship that followed. Cudjoe says Burnley was “most worried by the idea of a free labour class that would evolve as a result of emancipation.”

He participated in sourcing alternative labour from other nations to sustain the sugar estates.

Post-slavery, Burnley still benefited handsomely from the compensation awarded to planters for the loss of their previously labour force – compensation he had some influence in campaigning for.

Burnley lived at his Orange Grove Estate until his death in 1850. His stately mansion was demolished in the 1960s. Today, only a coolie pistache tree stands where his mansion once did, south of the Eddie Hart Pavilion, a lone reminder of a complex and often painful history.

Comments

"William Burnley, enemy of emancipation"