Mario Lewis takes art lovers beyond the forest canopy

In a large open space that could qualify as an unfinished room or an art studio, overlooking Morvant, Mario Lewis spreads a canvas on the floor and reveals a star-studded, indigo-blue sky.

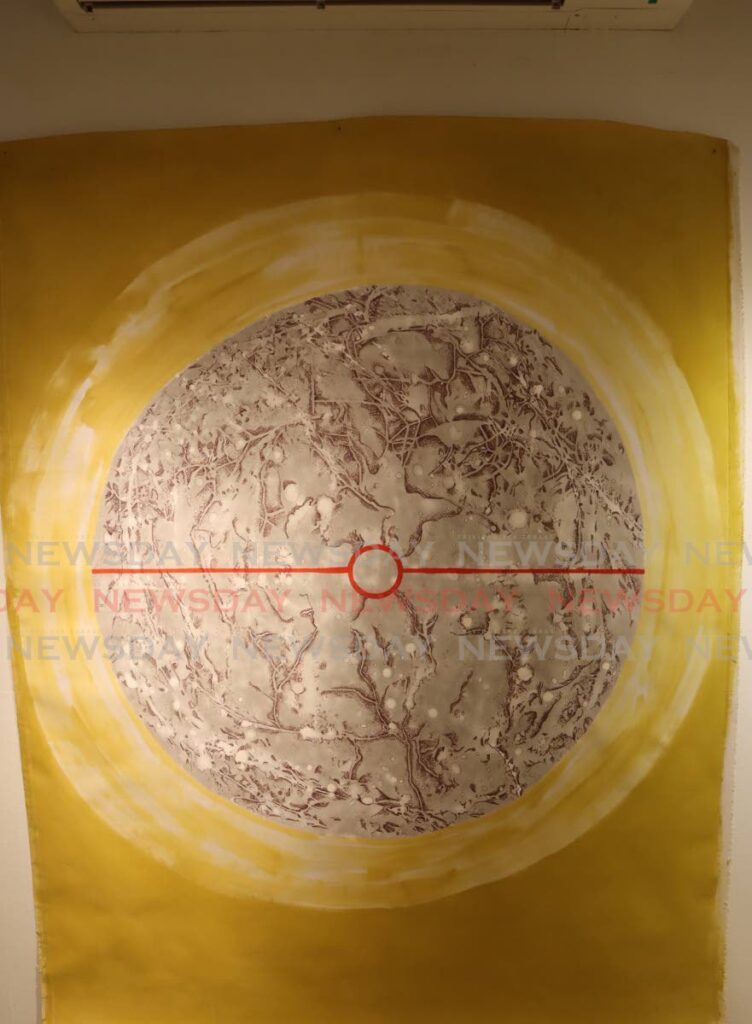

The universe unfolds on another canvas.

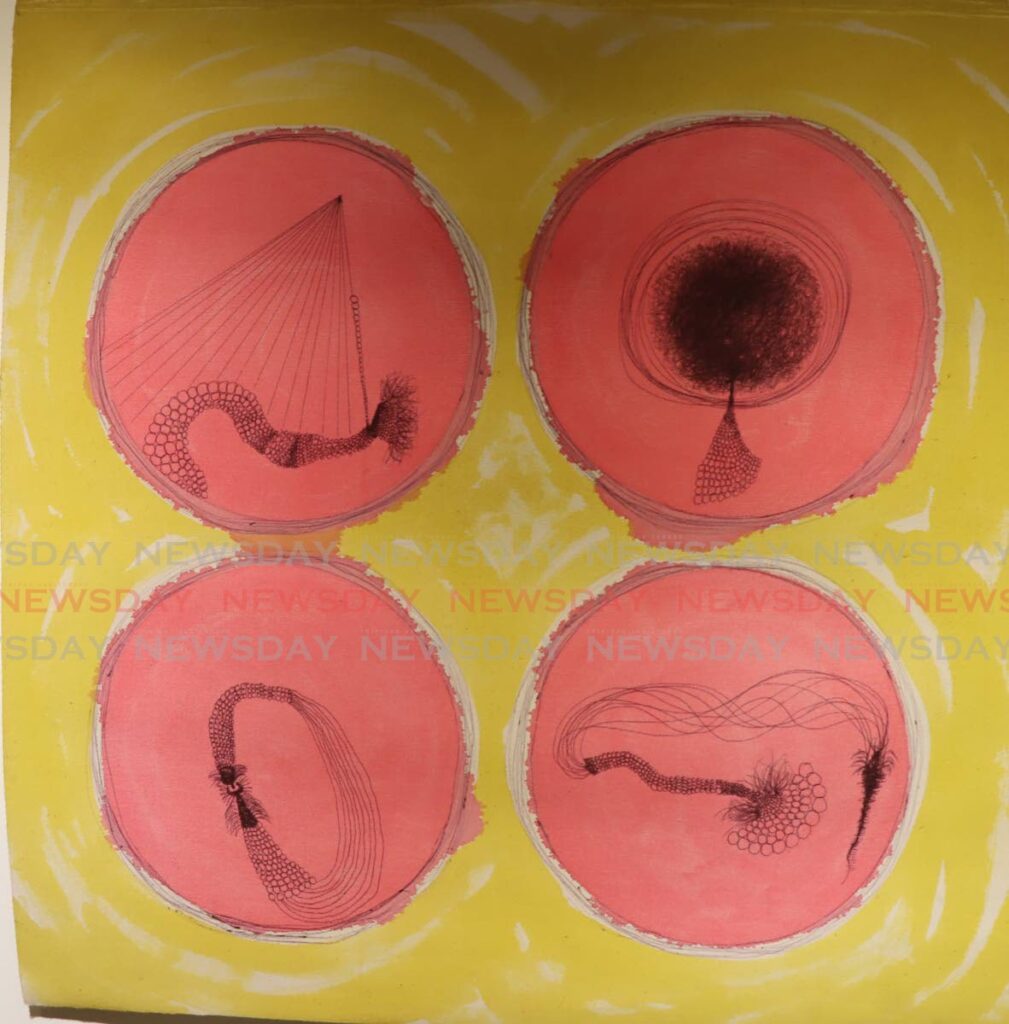

On a table with nothing but a cup of black-ink ballpoint pens, he places black-and-white drawings on card stock of a snake and small forest creatures – ants, earthworms, grasshoppers, spiders, slugs, millipedes, snails, bees and nematodes (small, slender worms that feed on fungi and bacteria).

His early drawings of forest life are simple and realistic, though they penetrate what we see with the naked eye to expose the internal structure of these creatures. Surely this is art.

But Lewis, who was born and raised in Santa Cruz, said, “I wouldn’t describe myself as an artist or what I do as art.

"I was trained to do art. I make something I hope is called art. You can have a conversation around it as art, but it’s not limited to art, so what is it?”

Lewis, a Unesco fellow in 2001, travelled to Italy to do an art residency. He studied at the University of the Arts (formerly Instituto Superior de Arte or ISA) in Cuba, one of the foremost art schools in the Caribbean, and Goldsmiths, University of London, which specialises in creative, cultural and social subjects.

Lewis said he tries to unlearn his formal education in art, but he has an interest in “and a lot of respect for science.”

Three of his five children work in science.

“I try to figure out why none of them are interested in art.”

Lewis has a keen interest in the composition of soil.

“I spend a lot of time observing the soil because it’s the main thing that gives life to organisms and plants. The more fertile the soil, the healthier the life above. I look at the texture, colour and moisture.

"Good soil is very loose, dark and crumbly, has a sweet smell, and a nice feeling in your hands. It has good drainage, allowing oxygen to pass through. There’s a lot of organic material – leaves, dead animals, plants and organisms in it.”

In 2016, Lewis bought ten acres of land which was part of a colonial cocoa, coffee and citrus plantation in Mamoral, located near Tabaquite and Talparo. He spends weeks at a time there sleeping in a tent, using candles for light. He collects rain water.

In 2020, Lewis found solace in his estate during the covid19 pandemic where he spent weeks at time under a tent.

“This was unprecedented and scary. I was unemployed. It created a lot of difficulty for me and my family. I asked myself, 'Is there something I can do to balance this off so I don’t get depressed?'”

He collected paper, ballpoint pens and notebooks – then headed for the bush to sketch and write observations like this: "Monday February 20, 2020. Weather conditions: Cloudy with slight showers. Maintain focus on zone (location on land). Cut palm tree branches and heliconia.

"Method: Cutlass, pruner and handsaw to remove vines and small hardwood branches. Application: Select large palm tree for pruning. Remove heliconia to create more visual of landform.

"Note: Slight improvement increasing slowly. Able to measure progress on each day. Creating natural drainage. Would need to map water course. Sighted small black and white snake.”

He explained, “Being alone in the forest allowed me time and space to meditate and do serious observations of where I am in life and what I want to do.

"I didn’t want to go in there as a conventional, dominating man. I wanted an understanding of what was going on there. The drawings manifested themselves.”

He realised the forest offered a way to deal with the pandemic.

“In an urban environment, you don’t have security, safety or the ability to sustain yourself. But in nature, there are survival choices. I wasn’t scared. The land gave me a perspective on my existence. Life wasn’t about having a car, a job or living in a big house – the typical things we all aspire for.”

Here was a place to experience time, space and life on a new level. It wasn’t that he saw an ant walking across the forest floor or a patch of grass or a wild flower springing from the ground. He saw inside the ant or under the ground.

“An ordinary black ballpoint pen was the best artistic tool for me. I wasn’t bothering about paint. The pen was comfortable and allowed me to break away from the educational mode that insists the best paintings take certain art supplies.”

First, he used eight-by-eight-inch cardstock paper. When he began to work with scale, Lewis moved to large canvases – six by five feet – to explore the sky and universe.

“I dealt with the imagination first and became a specialist looking for a particular type of ballpoint pen and ink. The point of the pen and the weight are important.”

The surface of what he uses – canvas, board, paper– dictates which pens to use.

“I’m learning the tone and the weight of the lines. Not all pens can be used on every surface. It’s all about problem-solving and scale. It’s almost like I’m creating a manual for myself.”

In the pandemic, Lewis discovered he enjoyed being alone.

“I enjoy companionship, but if I was working in a job thinking about my bills, I couldn’t have produced this work. I would never have been able to sink so deep into my creative process.”

He has no concept of time in the forest, only a sense of presence.

“I’m totally immersed in what is in front of me. It’s like being in a dream. When I get in the truck and leave, I deal with the mundane world.”

Back in Morvant, he draws from memory what he observed in the forest.

“The abstract part of the work is where I’m finding the mastery. I have no perceived notions of what I’m going to draw.”

There’s no explanation for the depths that he goes into in his drawings. It’s reality, but it’s also an experiment designed to penetrate deeper layers of time and space.

From forest creatures to dirt teeming with organisms, his pens capture a slice of life like a biologist does with a slide.

In his drawings of the universe, Lewis imagines space as a satellite would see it. It’s an out-of-body experience.

“Observation is essential in science and art. Unintentionally, I use some aspects of the natural sciences to carry out my artistic process,” said Lewis.

“I draw to collect and record my interactions, fascinations and theories. Learning new knowledge about my encounters in nature heightens my sensitivity, which I try to record through text and translate through my drawings. I seek evidence to help me figure out which of my theories is correct.”

Lewis feels the solitude he experiences in the forest helps him “to unravel unconscious thoughts about concepts concerning food, health, preservation, the molecular structure of cells, the function of microorganisms and roots in the soil, to the physical characteristics of the landscape.”

But how does this translate into the meaning of a Lewis drawing?

There will likely be as many interpretations of Lewis’s work as there are viewers when his exhibition runs from November 1-December 20 at the Medulla Art Gallery, 37 Fitt Street, Woodbrook.

Comments

"Mario Lewis takes art lovers beyond the forest canopy"