Sea creatures thriving together

In The Last Dance, Venom, Eddie Brock’s symbiont makes the ultimate sacrifice for his host-partner. That’s how coral reefs work. Dr Anjani Ganase, marine biologist, looks at of examples of ocean species cooperating for mutual benefit.

We get by with a little help from our friends. This is not just a song lyric but a rule of survival in the natural world. We are often amazed when animals (or plants) of different species form working partnerships or social interactions, but these relationships are common and referred to as a symbiosis.

The long-term biological relationship between two or more species where at least one species benefits is an example of symbiosis. When the partnership results in both partners benefiting, the type of symbiotic relationship is referred to as mutualism, when one benefits it’s called commensalism. Of course, there are scenarios where one partner is harmed in the process and that is called parasitism.

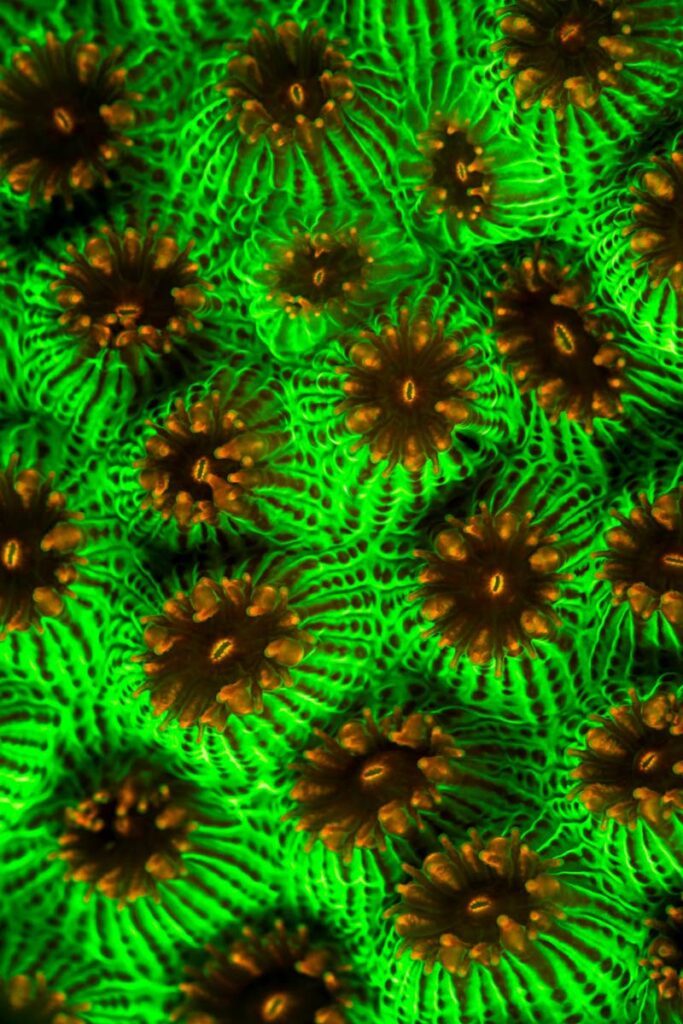

Corals and microalgae

Over 210 million years ago during the late Triassic period, corals ancestors were more similar to their jellyfish cousin. They would fix themselves to the bottom of the ocean and extend their tentacles out to capture passing prey.

Through evolutionary divergence, some corals began to ingest micro-algae, known as zooxanthellae, which eventually got incorporated into their tissue. The algae found sanctuary away from predators but also continued to grow and generate food from the sunlight. In return, the excess food created by the algae was given to the coral host.

This unique relationship is referred to as endosymbiosis where micro-algae completely live within the host to form a mutually beneficial relationship. The era of the endosymbiosis correlates with a period of significant coral reef expansions across the world along most tropical shallow water habitats that tend to be low in nutrients other than the supply provided by the zooxanthellae.

Another example of the mutualistic or symbiotic relationship occurs at the other extreme of ocean. Along the seafloor of the deep dark ocean, life prevails in and around hydrothermic vents and on seabeds rich in minerals. Instead of algae harnessing light for corals on coral reefs, we find chemosynthetic bacteria harnessing chemical energy to produce food for deep-sea invertebrates, such as crabs, deep-sea tube worms and mussels The invertebrate hosts provided homes in or on their bodies for the bacteria.

Clownfish and anemones

A clownfish is never without its anemone. Another relative of the jellyfish, the sea anemones have stinging tentacles for capturing prey, however, clownfish has the luxury of calling this deadly place home. The clownfish has developed a mucus layer that protects it from stinging cells.

While the clownfish provides nutrients to the anemone by supplying its waste, the clownfish also rids the anemone of parasites and protects it against other feeders. The clownfish also receives protection from the sea anemone, in fact they hardly stray far from the anemone and would lay eggs close to it. While anemones do exist in the Caribbean, clownfish do not. Caribbean anemones form symbiotic relationships with shrimp and crabs.

Hermit crabs and gastropod shells

Ever wonder where hermit crabs get their shells from? Hermit crabs are critically dependent on the shells of others for living and protection. As hermit crabs grow they look for larger shells, if available. Scientists were recently able to prove through experiments that the hermit crabs were not thieves of gastropods, and not capable of removing the shells from living sea snails. In fact the crabs had to wait for the sea snail to die and the body degrade before inhabiting the shell. This is a commensal relationship.

Given that sea snails are not overly abundant on the reef, a lot of crabs actually dig up fossil shells found in the sandy reef bottom. Under unfortunate circumstances, especially on degraded reefs, hermit crabs may have to find a substitute for shells such as plastic caps or other bits of garbage for shelter.

Another example of commensalism are remora fish that attach to the bodies of sharks, manta rays and other large marine animals. The remoras feed off the food scraps from the shark and hitch rides by attaching to the shark’s body by their suckers. The shark is not affected by this relationship and they can shake them off, if they get annoying. We have seen eagle rays and reef shark leap out of the water and belly flop to rid their undersides of clingy remoras.

Sharks and cleaner fish

Another example of a mutually beneficial relationship are the coral reef cleaning stations set up by cleaner fish and shrimp species. Open water megafauna – sharks, turtles, mantas, etc have been observed to visit coral reefs not just for food and refuge, but to get cleaned. On a specific coral mound resident cleaner fish and shrimp can be seen dancing around inviting the large animals to come by for a scrub.

The turtle may rest on the mound but fish or mantas hover gingerly over the mound long enough for the cleaning crew to hop on and graze off all the parasites, dead tissue, even old food scraps stuck in their teeth, as the cleaners fill their bellies. The relationship is one that pays for good behaviour. If the cleaner fish nibbles too hard, the client will leave and never return. Similarly, if the shark decides to gulp the fish, it will be banished from the cleaning station and never be welcome again.

Grouper and octopus

Groupers are known to be social hunters on the coral reefs. They can signal to a nearby eel or octopus of a prey that it needs help hunting. Because most prey hide in the tiny spaces of the reef framework to escape predation, the grouper relies on the stealth and agility of the octopus and eel to access these tight spaces. The job of the eel or octopus is to flush the prey out into the open to be nabbed by the grouper. The relationship is mutually beneficial, since the grouper will share its meal with his hunting party and vice versa.

Shrimp and goby fish

On the reefs of the Pacific, the goby fish that live in sandy burrows have become roommates with an unlikely creature, the pistol shrimp. The pistol shrimp diligently conducts its daily chores of clearing out the burrow of sand, while the goby stands guard at the entrance to protect the shrimp from predation. The fish will also find algae for the shrimp to feed on. The shrimp keeps one antenna on the body of the fish to detect any alerts made by the fish. This relationship makes for a happy home.

Nature proves again and again that symbiotic relationships are important not just for survival but for thriving. Imagine the possibilities if humans decided to live symbiotically with trees. We would have tree-grown homes bearing fruits. Imagine if we shared spaces with wildlife, we might also learn a thing or two. Biodiversity is the future for bioengineering, food security and even social development.

Comments

"Sea creatures thriving together"