Life on the surface of the ocean

Dr Anjani Ganase reveals the intricate web of life that exists between water and air off our shores

As budding marine biologists, some of our first introductions to the ocean did not include exciting encounters on exotic reefs or swimming with dolphins. Rather we were introduced to the very top layer of the ocean and the marine creatures that lived near the surface of the water. These creatures are referred to as a neuston community. Neuston is a Greek word for “to swim” and “to float”. Skimming a net along the surface of the water, we would find a collection of transparent shapes and drifting forms that were larvae of fish and invertebrates and other marine critters. In her recent publication, Rebecca Helm, assistant professor at the University of North Carolina, reviews the complexities of the neuston zone around the world and discusses the threats to these communities that reside in the interface between air and ocean at the “frontline” of impacts from human activities.

Neuston swim on by

The next time you go to the beach, dive just below the surface. The narrow surface layer stretches around the world and the communities that occupy the surface are as varied as the habitats below. Yet very little is known about the neuston communities. Physically, the surface of the ocean is the interface where mixing is brought about by the wind and allows the exchange of gases. The Sargasso Sea in the North Atlantic Gyre is probably the most well-known example of neuston community gathering or hotspot where marine biota utilises the drifting framework of the sargassum to seek refuge as well as to find food. It is thought that the surface of the ocean is not uniform, rather there are areas where the marine neuston communities gather either because of high productivity or because of currents and water movement. The marine creatures are also thought to reside in these locations for a part of their life cycle before other currents relocate them to other habitats.

Neuston Living

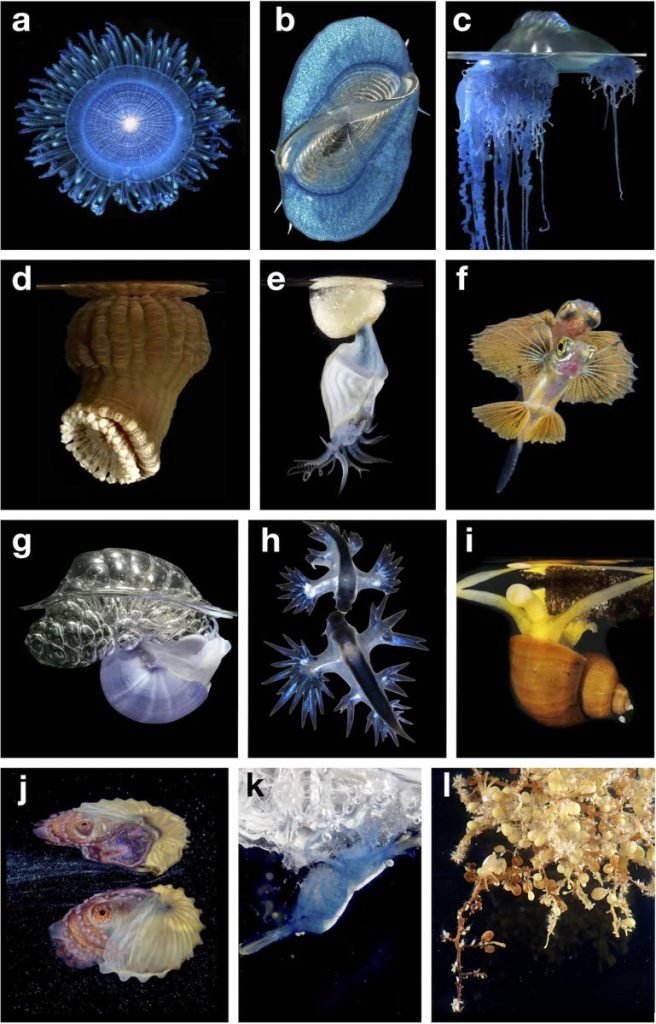

Organisms from the deep sea, coral reefs and even freshwater rivers and lakes all live on the surface of the ocean at some part of their life cycles, while other creatures reside in this zone for their whole life. The neuston community consists of a combination of juvenile fish and fish, jellyfish, anemones, barnacles, sea dragons, sea snails and seaweed (sargassum) plus larvae from an array of marine organisms. The fish present may include pelagic species, such as mahi mahi, swordfish and marlin, as well as reef fish, such as damselfish, blennies and seahorses. Some of these species are of commercial importance. Other species are invertebrates such as jellyfish and organisms that are adapted to float on the open ocean using air bladders and sails. Once grown to adults the fish can relocate to other habitats. Spawning events replenish the community by allowing currents and wind to corral new marine life to the surface.

The surface also supplies food to several fish, sea birds, marine mammals and marine turtles. In the North Pacific, 80 per cent of the loggerhead turtles’ diet come from neuston predominantly made up of a species of jellyfish called Velella velella, also known as sea raft, that looks like a jellyfish raft with a sail. Seabirds, such as shearwaters and albatrosses, often search for food just below the surface of the water. One well-tracked lifecycle is that of the American eel which journeys far offshore from the American coastal rivers to the Sargasso Sea where they reproduce by spawning. The fertilised eel eggs and juvenile eels eventually find their way back to the coast and up rivers and lakes with assistance of the gulf stream and currents. The return journey can take many years and when the eel is about ten to 25 years, it makes the swim back to the Sargasso Sea to reproduce.

The varied lifestyles and life cycles of neuston residents makes the surface zone incredibly dynamic and complex. Micro-organisms migrate vertically every day, shifting between the surface and the deep ocean for daytime and night-time routines. The vertical migration is often driven by environmental cues, such as light and temperature, as well as factors, such as predator avoidance and mating. The community also shifts seasonally in accordance with the life cycles of species.

Neuston, we have a problem

Unfortunately, the surface of the ocean is probably the most disturbed by human activities or small scales or global climate change. Near to shore, pollution runoff and chemical discharges, kill or impair marine larvae. In some areas, pollutants become most concentrated nearshore with fluids such as oils and fuels that kill the microorganisms and prevent gas exchange. Oil spills are unfortunately common around TT, and while we may be efficient at clean up, the dispersants also add to mortality.

Plastic pollution also affects the floating neuston communities. It is especially devastating to the seabirds, marine mammals, and turtles that feed on the neuston community. Scientists have recorded up to five tons of plastic being ingested by a colony of Albatross chicks on Midway Atoll in the Pacific. The plastic pollution gets trickier when considering actions to clean it up, as the garbage patches occur in the centre of oceanic gyres, which are also likely to be neuston hotspots of high biodiversity. How can ocean clean ups avoid removing significant amount of the neuston faunal populations?

Finally, climate change is causing the surface of the ocean to warm faster than any other part of the ocean. The surface is also exposed to extreme storm disturbances. Warming conditions in the ocean creates thermoclines that act as physical barriers in the water column and disrupt vertical movement of micro-organisms. With so little research and monitoring, it is difficult to say what the last 100 years of industrialisation have done to marine communities.

A neuston perspective

Understanding how the ocean surface and ocean gyres are connected to the populations of marine life found off our shores is the first step to understanding the importance of management of marine life beyond our national borders. There is a need for more research into potential neuston hot zones and modelling their connections to other ocean habitats and seas. We must also understand that the surface ecology is closely tied to our nearshore ecosystems and the many marine travellers they attract. Sea birds that reside in Tobago feed way offshore; migrating whales feed in these hotspots and visit our shores. No longer can we view the ocean as a remote entity. The ocean is our backyard, an interconnected web of marine creatures in habitats as diverse as we see on land. We are part of this web.

Comments

"Life on the surface of the ocean"