Daughter of coup hostage Raoul Pantin recalls broken family

WHEN 14-year-old Mandisa Pantin heard that her father, journalist Raoul Pantin, was being held hostage, she couldn’t believe it.

This was only the beginning of a trauma that would tear her family apart.

Thirteen years before the coup, her earliest memory of her father was of wearing a brand-new dress and her father taking her for a walk around the Savannah.

“Everyone kept asking, ‘Where you get that pretty little girl from, Raoul? You kidnap the child?’”

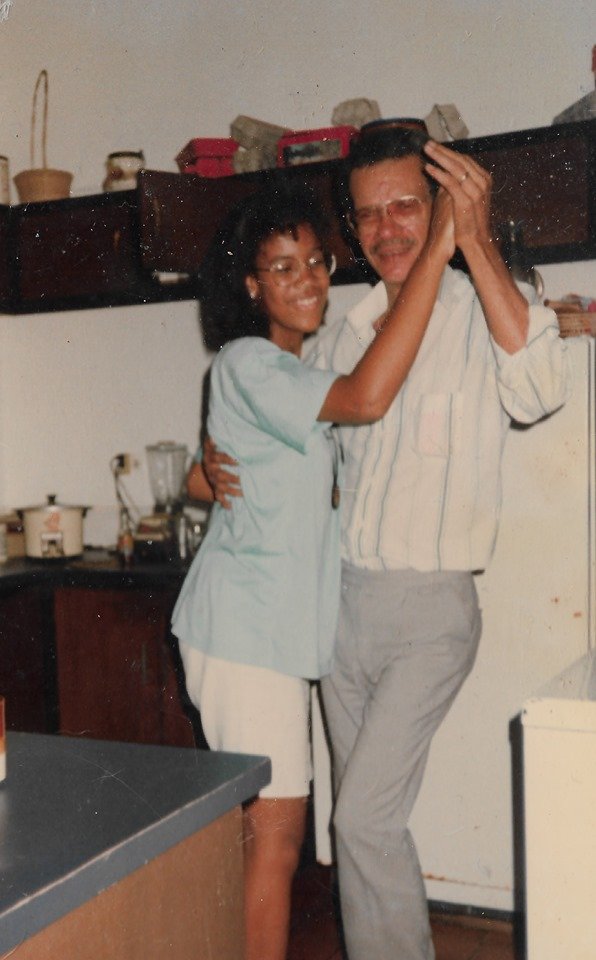

She said all her life she was called “Raouletta” because she looked so much like her dad.

Raoul Pantin (June 5, 1943-January 15, 2015) was a journalist, editor, poet, playwright, author and screenwriter. As a journalist he worked on radio, at newspapers – the Express and the Guardian – and on television on TTT.

That was where he and 25 others were held hostage for six days by the Jamaat al Muslimeen during the 1990 coup attempt.

IS HE ALIVE OR DEAD?

At the time of the attempted coup, Pantin’s parents were married and living together in Santa Cruz. Mandisa was organising rehearsals for her band (she can’t recall the name), which was to take part in the weekly television entertainment showcase Party Time.

On the evening of Friday July 27, 1990 her mother, Christine Jorsling-Pantin, dropped her off to the rehearsal space in Barataria.

“And she comes racing back to pick me up (before 9 pm, when rehearsal time was supposed to end). And I am upset. I’m like, ‘You are killing my rehearsal time.’

“She’s like, ‘You have to come into the car now.’ And she wouldn’t tell me why. When we were almost home she said, ‘I have something to tell you…We believe your father is being held hostage.’

“And I was like, ‘What? Wasn’t he supposed to do news tonight or something?’”

Her mother told her that TTT and the Red House had both been taken over and the police headquarters blown up.

Pantin did not take her mother seriously until they got home. She recalled the television was off, which was a strange thing in their house because it would be on to “see Daddy on TTT.

“And then the weird footage started to come on. I just remember seeing (attempted coup leader Yasin) Abu Bakr on television and I am like, ‘Okay, this is really happening.’”

Next morning, when she and her mother woke up there were army personnel outside their house with guns.

They wondered, “‘Are they coming to kill us? Or are they coming to protect us…What is going on?”

“But they came to protect us, thankfully.”

There were four soldiers. Two stayed inside the vehicle. They told her mother they were there to watch the house. The presence of soldiers with big machine guns outside their home caused “quite a stir.”

Asked if the soldiers made her feel safer or less safe, Pantin replied, “Uncomfortable.” After her mother fussed about their presence, the soldiers retreated into the background , by the third day.

It was a strange time because her friends were going to “coup limes,” “curfew parties” (at 14, she was too young to go) or to the mall during the day.

“And I can’t go anywhere…So it’s two things happening: teenage angst, can’t make a move; and is my father dead or alive? Every single day.

“Having to question whether your parent is alive or not is sort of difficult to deal with. I don’t think we slept for most of that time.”

She and her mother did not talk about the situation, but she did talk to her boyfriend and friends “ad nauseam.

“For me (talking to them) was helpful. At least I was able to process it through talking through it. I mean nobody could say whether it was going to have a brave resolution or a bad resolution. All the people could say is, ‘I’m listening to you.’”

She knew her mother was trying to find out if her father was okay, if he was getting food and if she could get clothing to him.

“Nobody (at TTT) was able to move. And when the barrage of bullets (hit the building) you started to get very worried. I don’t remember what day that was. But you started to get very scared. And the whole family started calling, because nobody could come to us.

“It was like covid. We couldn’t go anywhere, and nobody could come to us. So were very isolated…And I don’t think being isolated was such a great thing, because you get more concerned. And you don’t know what is good news, what is fake news.”

GOOD NEWS AT LAST

She recalled her mother getting one very brief phone call from her father while he was still a hostage, towards the end of the ordeal.

“I don’t know what he said to my mom. He didn’t talk to me.”

All her mother said was, “‘He’s alive.’”

She felt relief at the news and after that things got a little better. The following day her father and the other hostages were released. But none of the officials would give her mother any information and they had to watch the news along with the rest of the population.

Her father was taken to Camp Ogden (a Defence Force camp in St James) for five days for debriefing and psychological evaluation.

“The army chose to hang around. They weren’t as present, but they were kind of still checking on us. Every now and again we would get a knock.”

The soldiers were very polite, very respectful and kept their distance.

“They didn’t feel invasive, but they were just kind of frightening.”

After Camp Ogden her father was supposed to return for recommended therapy sessions, but she does not believe he went for enough of those sessions.

“Because I think he declared himself cured within a month. (But) that’s not true.”

Her friend, Dion Boucaud, later made a documentary film called The Siege about the coup hostages and there is a shot where her father is reading from his 2007 book Days of Wrath about the attempted coup and his experience as a hostage.

“He says he went to Camp Ogden for five days, went home and lived happily ever after – and then he laughs. Because it’s not true.”

NEVER THE SAME

And what was her father like after the traumatic experience of being a hostage?

“As I said before, my father wasn’t an easy person before the coup.

“But after the coup? I now utterly understand what PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) does to people. I think everybody reacts differently.

“But definitely there is a kind of psychotic break that happened, where he was not behaving rationally. And he would be able to hold it in for a while where he’d be okay.

“(Then) bam. Anger and paranoia. A lot of paranoia.”

She interviewed him afterwards for a film she herself has been trying to make about the children of the coup victims.

“And he said after 1990 he was never the same. He never felt the same. And it took him a long time to figure out why. Because people would talk about PTSD then, but they wouldn’t really put stock into it. And everybody was like, ‘You just behaving bad. You acting out. Behave.’

“That’s not true.”

She did not want to go into the details of how the anger and paranoia manifested. Her parents split before Christmas1990.

“Nobody could seem to help.”

But her father did not want help, as he had declared himself cured.

“The effect of that level of violence and deprivation on a human being doesn’t only affect the human being. It affects their family. It affects their children. It affects their life structure. It affects everything.

“And that’s why I still find it hard to talk about it now.

“If I was locked into what I felt was like an unending nightmare for a while, I can’t imagine what his mind would have been going through.”

BROKEN AND MENDED

After 1990 she and her father were estranged for years. They saw each other every year for her aunt’s big Christmas lime and he met Mandisa’s daughter Jaliyah. They spoke two or three times and would just say “hi.” When she turned 18 they tried to reconnect for her birthday, but it did not work out very well.

In the intervening years Pantin went to therapy.

“I had to. I had to. Then I had a child and I became a single parent.”

She also became a victim of violence herself. She and her mother had a store in Belmont, which sold stationery and offered computer services, an internet café, gaming and graphics. But she was held up at gunpoint ten times and the store was held up even more often. She decided to close it.

“At that point I had to go for therapy. Because that’s when I started to understand how Daddy felt. Because I couldn’t sleep. I had to be watching behind my back all the time. I still am kind of paranoid – but that’s okay, it’s healthy.”

Did she read her father’s book about the attempted coup?

Not until years after its publication, because she was very angry. The experience was painful, but she was glad she read it.

After she read Days of Wrath, she felt she could relate to her father and they could maybe talk.

“Especially the description of when they were under bombardment. Or even the description of when they were first aware there was a coup happening. And he kind of describes it as like a surreal moment. I get it.

But she did not reach out to her father. It was about 2010, two decades after the coup attempt, that her father contacted on Facebook and they had a real conversation. They met in person and the first thing they talked about was the coup and the aftermath.

“And the more we got together and spoke – because now both of us were older – is the more we were really able to form back a relationship. To the point where I would leave my daughter by him when I had work. Because you know how working in the media kinda go.”

Her father absolutely loved his grandchild. He was not one to say, “Oh my gosh, I love you so much,” to his granddaughter, but he would say, “Kid, read this.”

She, her daughter and her father also shared a love for dogs. He had a dog named Saddam, after late former Iraqi president Saddam Hussein, and when she returned from work her daughter would be cuddled up with Saddam and her father would be on the computer and talking to her.

“So it had a happy…well, of course, he’s passed away now. But at least I am very glad that before he passed away we got back together. We got to have that relationship. Because I would have felt terrible if he passed and we hadn’t tried to at least reconnect.

“I don’t know whose fault it is. But that kind of trauma: I could have dealt with it better, he could have dealt with it better. But I don’t think either of us got the help that we needed.”

FEAR OF ‘REMEMBRANCE’

As for the 30th anniversary of the attempted coup, Pantin says, “Every time you see somebody on TV saying, ‘Oh we have to remember 1990,’ and them lighting a candle – that means nothing to young people. They don’t even care. They don’t even know about it.”

She said her daughter only knows because her grandfather was involved and he talked to her about it, though she does not know what he said.

“My poor child,” she laughed.

She said something new would have to be created, something “out of the box,” to get people to understand it.

Her father was a witness to the Black Power revolution and then a hostage in the attempted coup, but: “All these events are totally unreal to a segment of the population.

“And that is my fear about celebrating or remembering without actually doing something significant. What’s the point? It’s almost like a joke.”

She has been trying to make her documentary on the children of coup victims for a number of years but was stymied by a loss of footage, including interviews with her father.

“That’s my fault. I sat on it for too long. It’s just emotionally challenging.”

She wanted to do it not only to talk about the coup but to also talk about a father-daughter relationship, a dynamic that is rarely explored, and how a trauma affects that and families.

“We have to stop these…imported ideas of what does exist, and try to examine what it means to us, whether it’s personally or as a society or as a country. And…one of the most important things my father ever shared with me was love for country. Love for the environment. Love even through good or bad. And to listen before you judge.”

She said the coup is a very important part of the story, as it was a traumatic cycle not only for her and her father but for so many families.

“And everybody just wants to probably sweep it under the rug and say, ‘Oh yes, 1990, light a candle.’”

Asked why, Pantin replied: “If we as a society were to engage with our history at our various points in time, where we’ve had violent moments or crimes against humanity or anything like that, I think our society would boil rather than simmer. And what we are doing right now is just simmering. And that’s why we sweep things under the rug.”

If the whole society were to talk about things, “Either we would kill each other or a great resolution might happen.”

She was not sure which.

“If we’re gonna talk about the 1990 coup, we have to remember not just my dad, but all of the people who were held hostage. There are a number of people who people would never even remember who were also in that situation, whose families have also been affected.”

AVOIDING THE SHADOW

Mandisa Pantin said her father was a very creative person.

“I think he influenced me greatly in trying to do the impossible. And I think that’s what he achieved in his lifetime. He worked on television, newspaper and radio, and he taught me a lot in terms of that, and in terms of being very appreciative of being a Trinidadian.”

When her parents were together, her house was one where you would have CLR James (historian and socialist) and Beryl McBurnie (iconic Trinidadian dancer) and she never knew that was not ordinary.

“So I am not sure that I had a sense of what was supposed to be normal.”

Her godfather was the late actor Wilbert Holder, and she grew up in the theatre, spending many nights sleeping there while rehearsals went on until three in the morning and both her parents were there.

But it took a while for her to realise her father was famous.

“Until I went to high school and people started saying, ‘Oh, you’re Raoul Pantin’s daughter.’ I started to realise, ‘Oh, there’s a thing,’

“And then I started not saying who my father was, because it became an issue…

“‘No. I am me. Not anybody else’s offspring per se.’”

She did not want to be under her father’s shadow because it was disconcerting. If her father cussed someone or said something in the newspaper about them, they would want to attack her.

“I am only 11. Why are you talking to me?”

She also did not want to be in the public eye during the difficult teenage years.

“I’m always uncomfortable about being in the spotlight. I prefer to be behind the scenes at all times, as much as possible.”

In later life Pantin avoided the media for years or any kind of creative career except for doing graphics. She found the media landscape very “bacchanalish,” with a lot of interpersonal confrontation, and she also disliked the public aspect.

“And then I ended up doing film. I don’t know what happened. Something switched. And I think turned 30 and I was like, ‘Oh no, I want to have something that I actually want to do,’ and that’s what happened.”

Comments

"Daughter of coup hostage Raoul Pantin recalls broken family"