The price of the archive

BitDepth#1213

SINCE JANUARY, I’ve been posting some of my older photographs to Instagram (@thelyndersayarchive).

Some of the work has stirred interest and opportunity, because old photographs have an integrity and value beyond their subject matter. Styles of clothing, popular personalities, background details and recontextualisation all recast old photographs for the modern eye. Reviewing old contact sheets, I’ve been struck by images I’d considered inconsequential or marginal that have a very different meaning in 2019.

One of the results of that sharing has been an increase in requests for photos. That isn’t new either, but the big surprise has been how few people seem to be interested in paying anything at all for access to the work.

I have a body of work dating back more than four decades and it didn’t happen by accident.

My guiding compasses in building photo preservation systems came from Noel Norton, who already had an impressive archive when I started taking photographs, and Time-Life, which turned years of publication into a monolithic archive of imagery that seemed to be published everywhere.

There were many other photographers working at the time with much larger collections of excellent work. Much of it has disappeared. Some shot for newspapers which created libraries of published work but treated the larger corpus of unused creation like annoying chaff.

There have been two short engagements when I worked as a photographer on staff, first at an advertising agency, where I did a side project on Carnival 1979 that included my first photos of Minshall. That work was declared lost when I asked after it.

The second was the two years I led the photographic department at the Guardian, photographing the 1990 coup attempt. In less than three years, all those negatives had disappeared.

Add in the ill-considered moments when I trusted publishers with my original transparencies who never returned them and there’s a whole collection of early work that I still feel like the ghost of a lost arm.

Keeping work isn’t easy at all.

Norton suggested that I keep negatives in glassine pages (a type of neutral wax paper) rather than the more common plastic sheets. Turning analog film into digital files remains a significant challenge.

In the heyday of film scanning, between 1992 and 2000, high-quality, marginally affordable desktop scanners were available. They are not any more. It’s either Hasselblad’s Imacon or rubbish.

In short, keeping the work is hard work.

I built custom furniture in my office to house my negatives.

Scanning and correcting negatives and transparencies is hard work, often requiring hours of step-by-step correction to restore. Preserving digital versions is hard work. Master files are huge. Digital migrations from older media is time-consuming and expensive. Mass copies must be verified.

This isn’t unique to photography. Christopher Laird’s effort to preserve the Banyan video archive is without precedent in the region.

Yet it seems easy to decide that this work has no value. Companies will have meetings about work they need, consume executive time, plan for the costs of printing and framing then declare there’s no budget for the actual work itself. It’s history, they say. It’s for the culture, they claim.

If archived media is as ubiquitous as such arguments imply, why isn’t there more of the work around? Why was so much of it lost, discarded or stored so poorly it’s unusable?

So this is why I find it so easy to decline absurd requests. It’s disrespectful. It spits on the work, takes a whiz on the archiving effort and completely disregards the human investment.

“No,” is the very least I owe you in response.

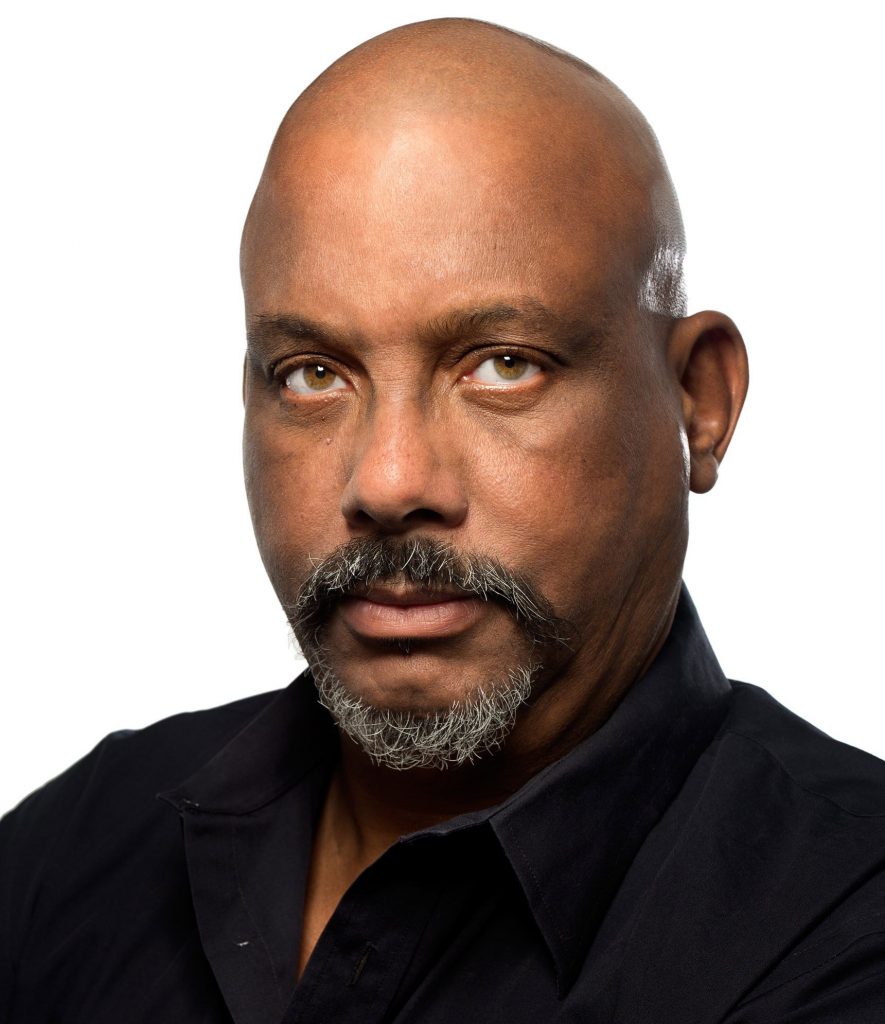

Mark Lyndersay is the editor of technewstt.com. An expanded version of this column can be found there

Comments

"The price of the archive"