The Colour of Shadows by Judy Raymond

The following is an excerpt from chapter 6 of The Colour of Shadows: Images of Caribbean Slavery by Judy Raymond.

This imaginative book throws new light on the closing years of Caribbean slavery and the lives of enslaved people of African descent before emancipation in Trinidad in 1834.

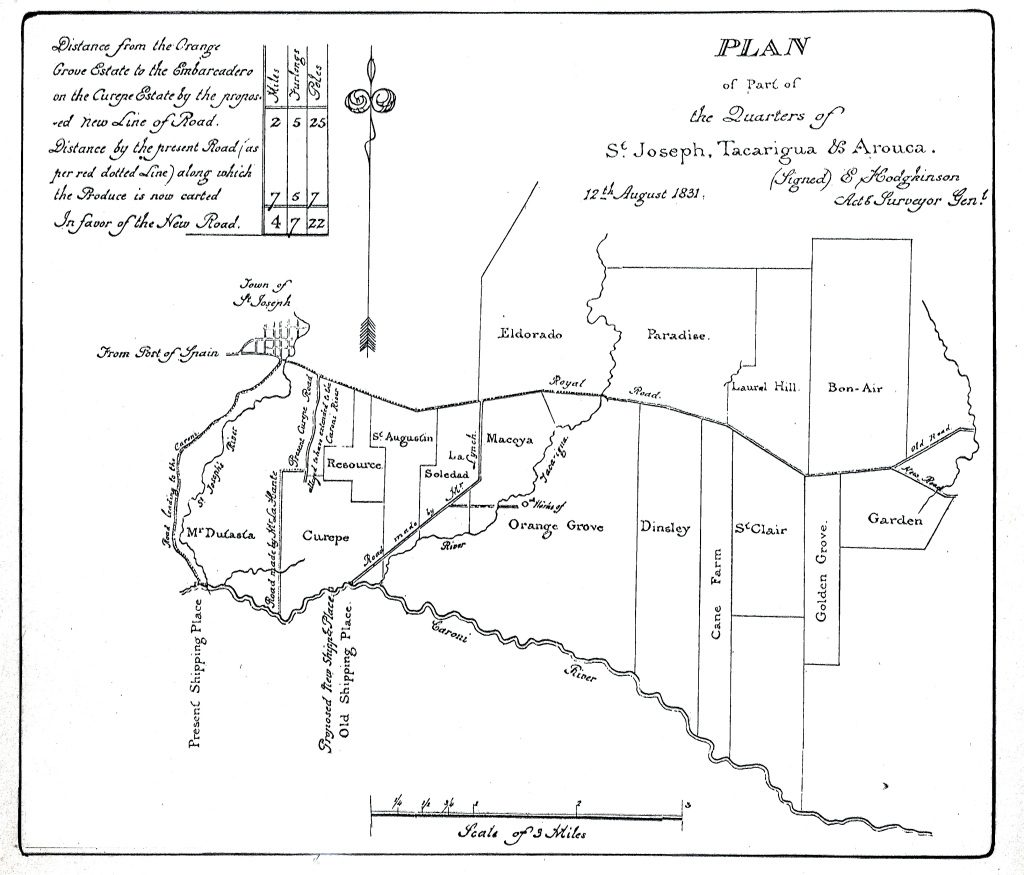

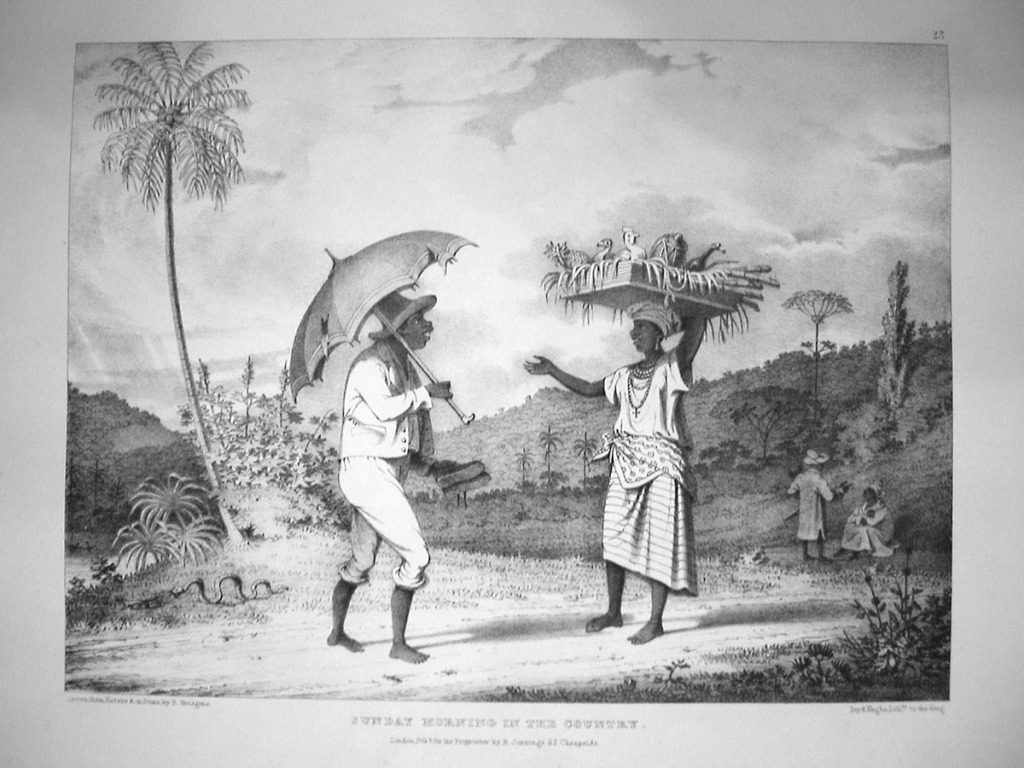

The book centres on the drawings of plantation life by Richard Bridgens, an English-born artist who became a planter and slaveholder in Trinidad, and examines these in the context of contemporary documents, records, and writings. The result is a detailed written and visual account of the everyday life of enslaved people, the conditions under which they lived and worked, and the new creole culture they were beginning to create.

Invincibly Human Beings

Tropical nights are full of noises. After the heat, that’s the first thing you notice, coming in from a colder place. A house in the country, like that at St Clair, would have been unbearably hot when closed, but perhaps unbearably frightening when left open at nights: the darkness loud with crickets, the deep-throated barking of frogs, the wind rustling and rattling through the cane and the bush.

Insects hurled themselves all night against the wooden jalousies: moths, flying cockroaches, grasshoppers, and rainflies by the thousand on wet nights when the roar of the rain could drown out a multitude of more sinister noises.

Tree frogs and lizards would scuttle over the walls inside. On the riverbanks, bamboo creaks and snaps; sometimes clumps of it topple under their own weight, banging and slithering together as though something or someone is creeping through it, until the long stems collide in a final leafy crash. That quieter pattering outside might be an iguana or an agouti in the bush, or it might be someone walking softly up to the window.

So in the big house, the nights were long, the planters restless. They would toss on their linen sheets, sticky with sweat because the shutters were closed against the breeze, rain and danger. Between the stars and the fireflies, in the deep, steamy darkness of the tropical night darker shadows walked through their dreams armed with cutlasses and flambeaux, and they came from the slave huts to take their freedom and revenge as they had done in other colonies: Haiti and Jamaica, Berbice and Demerara.

CLR James quotes the French revolutionary Mirabeau as saying that the colonists slept on the edge of Vesuvius. As James also writes, it didn't matter how badly enslaved people were treated, whether they were worked to death, or how brutally or how often they were beaten.

“The difficulty,” he wrote, "was that though one could trap them like animals, transport them in pens, work them alongside an ass or a horse and beat both with the same stick, stable them and starve them, they remained, despite their black skins and curly hair, quite invincibly human beings; with the intelligence and resentment of human beings."

The planters’ fears skittered through the night like the bats that emerged at dusk. The only light on moonless nights came from the fireflies flashing white against the dark forest and the yellow glow of the cooking fires outside the slave huts.

Once those fires were doused for the night, the enslaved workers slept the sleep of exhaustion, stretched out on mattresses of dried cane leaves spread over beds of planks or heaped on a beaten earthen floor – even when they were not working, they couldn't escape the cane.

Working on the estate

A bell would ring before dawn, the sound loud by the slave huts, but small and tinny by the time it drifted over the fields on the sharp breeze that rubbed the tall stalks together. On some estates, a conch shell would be the signal that the workday had begun though it was still dark.

Silently they would rise, too tired and low-spirited to talk. Pull on another rag or two, dash water over your face, tie your head to keep the sun and the sweat out of your eyes. Fill a calabash with drinking water, feel for your cutlass and hoe in their place by the door of the hut, and gather in the gang outside. Those who were late risked a flogging. By now the east was brightening, light rimming the small fleeing clouds, sparking off the blades of cutlass and hoe. The valleys of the Central and Northern Range were still in dewy gloom, the grass chilly and wet under the cocoa trees and the immortelles that shaded them. Out on the plains and the little hills of the Naparimas, the sun was already throwing knife-shaped shadows among the cane stalks.

Despite the dawn start, and even after the cool nights early in the year, the sun was harsh by mid-morning, and the workers stripped to minimal rags would soon have sweat running into their eyes, making the handles of their cutlasses slip in damp palms, risking a self-inflicted gash.

Worse than trudging into the fresh morning was going back to work in the still afternoon heat, after the two-hour break and a heavy meal. Plantain and cassava, eddoes and dasheen – starchy ground provisions, food of the enslaved – fuelled the long hours of work, but also made the workers sluggish.

Even when they finally left the fields, as the colour left the sky and the smouldering heat began to ebb, the long workday wasn't over. Field slaves had to gather grass daily for the estate's livestock.

With luck, the workers might not have to search far for grass from the sides of the tracks that served as roads, the edges of fields, and the bush beyond that was not yet cultivated. Still, it had to be done every day, before they could fetch water, cook, bathe, and rest.

The whip awaited them otherwise. Everyone worked. Mrs Carmichael reports blithely that children joined the “vine gang” at the age of four, picking wild vines to feed the livestock. At eight or nine they would be sent to weed the canes with hoes.

Minimising their labours, Mrs. Carmichael reported: “At first only three hours a-day with the hoe, and that not without intermission; the rest of the day they pick wild vines with their old comrades.”

At 16, she wrote, they were considered fit for adult work in the fields and in other gangs, classified according to their strength and capacity for work. There was no different treatment for women, except perhaps for those who had the misfortune to take the master’s or the manager’s fancy.

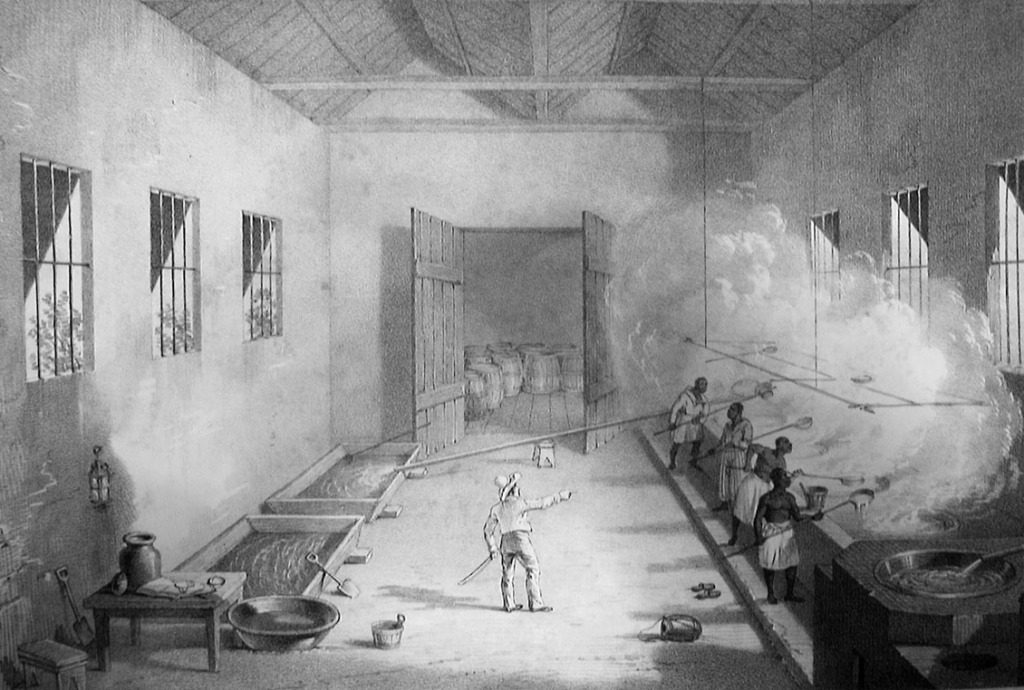

Men were singled out for training in skilled trades such as coopers, blacksmiths, masons, carpenters, distillers or headmen in the boiling-house. For women who were not house servants, there was no other option than field labourer.

The Anti-Slavery Society’s Abstract points out, “The drivers in using their whips never distinguish sex.” Some overseers would spare pregnant women from working in the fields. Given the high mortality rate among enslaved workers and their children, one might expect that they would be given special care to ensure that they and their babies were healthy.

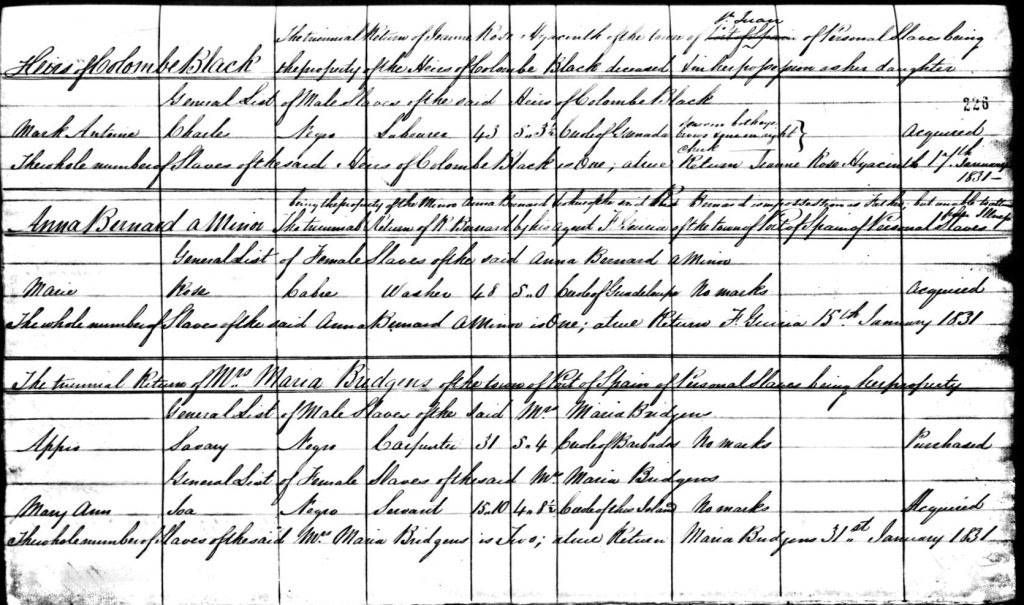

But in practice, most were expected to work exactly as usual. For instance, the first report of the Protector of Slaves for the second half of 1824 records a punishment at the Chaguaramas estate of Messrs. Lacrosse and Benoit Dert, where a woman named Françoise Masson was kept “En prison 24 heures.”

(This “prison” would have been a lock-up, also known as a cachot or the dark hole). Her crime was “Ne voulant pas travailler à conte de sa grossesse n’étant grosse que de six mois, et lui ayant donné des petit travaux.” (Not wanting to work because of her pregnancy despite being only six months pregnant, and being given small tasks.)

Before the 1824 Order in Council, field workers were summoned at sunrise (6 am), then worked till 9 am. After half an hour for breakfast, they would work until noon, eat their midday meal, resume work at 2 pm until sunset, and then fetch grass. Thus they worked for at least ten hours a day, six days a week.

Even these long hours were a reduction of those mandated by the Slave Code of 1800, when they could be forced to begin work before 5 am and work after 6 pm. How strictly the new rules were enforced is questionable.

But in any case, normal rules did not apply at crop time, when the estates worked day and night, and the insatiable rollers of the mill had to be continuously fed with fresh-cut cane. Domestic or personal enslaved workers might have lighter work than those in the field.

Those serving in the house might have food from the master’s table, better quality cast-off clothes, and did not work outside in the hot sun. However, being constantly under the eyes of their masters and mistresses left them “continually subject to be seized and mortified at their caprice.” This might mean punishment for shortcomings, real or perceived, in their work, and they were vulnerable to sexual assault. Furthermore, some “personal” enslaved workers were actually hired as domestics, or worked outside the house in various more or less skilled capacities such as washerwomen, carpenters, blacksmiths or travelling salespeople; women in this category might be forced to prostitute themselves.

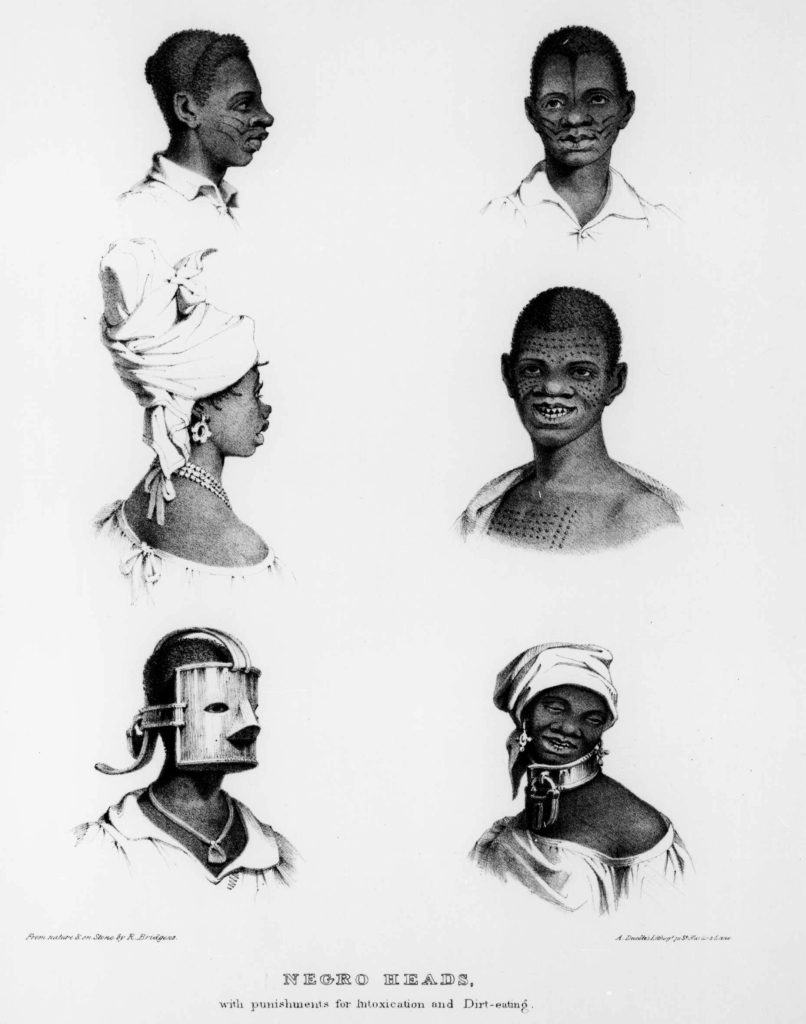

Punishment

When the office of the Protector of Slaves was established in 1824, a common complaint made to the Protector by enslaved field workers was that they were worked too hard. Many complaints were dismissed as unjustified, though often the evidence is sparse or confusing, because of the cursory notes made by the Protector and his assistants.

After 1824, drivers and overseers were not allowed to carry whips and there were rules about the administration of punishment: 24 hours were to elapse between an offence and the punishment so that it was not inflicted capriciously or in blind anger.

Until that time (and no doubt in many cases thereafter), overseers and managers routinely carried whips, and used them as they pleased for impromptu punishment. The Anti-Slavery Society noted that enslaved field labourers worked, "in rows, and without exception under the whip of drivers, a certain number of whom are allotted to each gang. By these means, the weak are made to keep up with the strong…from this cause many of them are hurried to the grave." (Italics in the original.)

Apart from the long hours, strenuous work, and horrific treatment, living conditions in general contributed to high mortality rates of enslaved workers. The homes to which field workers returned at the end of the day were places to sleep, cook, and store their meagre belongings and no more.

Huts were clustered together at a distance from the estate house. “Tapia” is a Spanish word meaning earthen brick, but in Trinidad – where a few tapia houses still survive – it has come to mean the wattle-and-daub technique that Richard Bridgens describes in the text to his drawing "Negro Mode of Nursing," which shows slave huts in the background.

He writes, “The walls, consisting of a kind of wicker-work, covered with a thick coating of mud, afford abundant protection in so fine a climate, and as they are kept neatly whitewashed, present an appearance of comfort which a European would not anticipate.

"The roof is thatched with what locally is called ‘trash,’ that is, the dead leaves of the canes, which are stripped off two or three times during its growth." Mrs Carmichael says the size of their huts depended on the rank of the enslaved people, and might vary between 15 feet by 20 to 25 by 30, with two or three rooms.

There are many far smaller old chattel houses still in Trinidad, Tobago, and other islands, so these dimensions seem implausibly large for slave huts. Those in Bridgens’ drawings, as well as being smaller than the dimensions given by Mrs Carmichael, are roughly built and not at all sturdy looking.

The roofs are steeply pitched, perhaps to encourage water to run off and, despite Bridgens’s claims, they do not look weatherproof against Trinidad’s torrential rains. They must also have been ferociously hot and stuffy (even, or perhaps especially, in the the rain), with the door and one tiny window with a wooden shutter as the only openings.

Inside, many occupants not only had no beds but also no bedding, except cane leaves or a coarse blanket. Some had boards or mats to sleep on, and perhaps stools or benches. Cooking was done on a fire outside, perhaps in a coalpot; a tiny iron stand in which charcoal was burned under a metal grill on which the cooking pot rested.

In wet weather, the coalpot would be brought inside or set in the doorway if the rain was not blowing inside. A Dr George Pinckard, writing in 1806, described slave huts in Barbados as being “commonly of very coarse construction…dark, close and smoky.”

Comments

"The Colour of Shadows by Judy Raymond"