Black Light Void rare, interdisciplinary reflection on art

Gone are the days when we could pigeonhole most books – fiction or nonfiction – into one specific genre. Authors and editors are crossing and blending genres often to encourage wider and more challenging readings. It’s been happening regularly in fiction, and more often now in nonfiction – particularly with biographies and history – but a December visit to Waterstones bookstore in Glasgow, Scotland showed me this is happening in art books too. There I bought Thunderclap: a Memoir of Art and Life and Sudden Death by Laura Cumming. The author’s memoir juxtaposes the story of her artist father’s unexpected death with that of a Dutch painter, Carel Fabritius in Delft, Netherlands, in 1654. So there’s history, culture, art, and memoir all blending together.

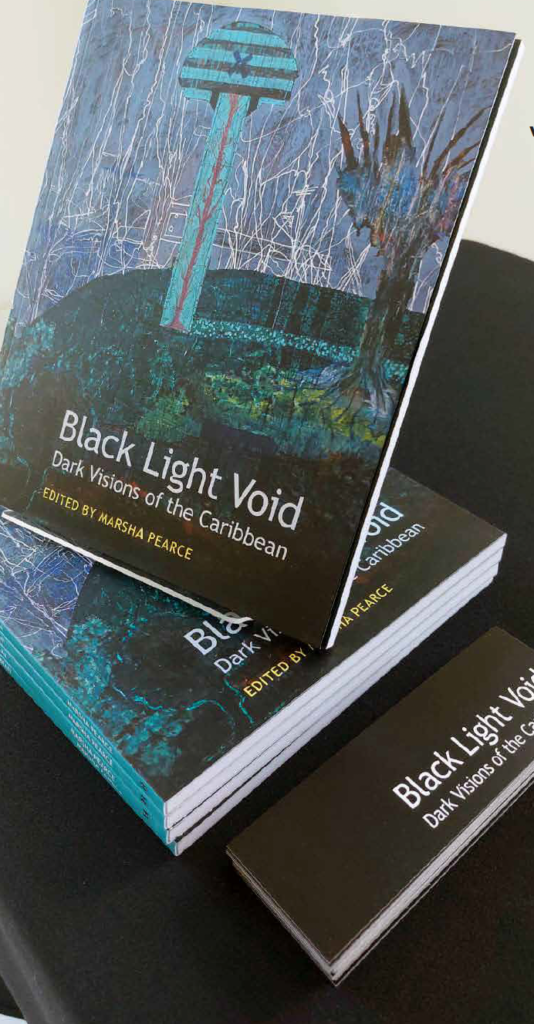

The recent launch of a local book, Black Light Void: Dark Visions of the Caribbean edited by Marsha Pearce, a lecturer in visual arts with a PhD in cultural studies, offers a far different experience. Pearce has curated pictures of paintings by artist Edward Bowen and creative work by six writers: Kevin Jared Hosein, best known for his critically acclaimed, internationally popular novel Hungry Ghosts; Barbara Jenkins, author of the novel De Rightest Place and her recent memoir The Stranger who Was Myself; Sharon Millar, award-winning author of The Whale House; Amilcar Peter Sanatan, poet and PhD candidate in cultural studies; writer and artist Portia Subran; and Elizabeth Walcott-Hackshaw, UWI professor of French literature and creative writing. Together they offer imaginings on a selected few of Bowen’s dark acrylic paintings.

In the book’s foreword, Pearce puts the paintings and stories in perspective and offers some art critiques and summaries of the writers’ stories. Her background in cultural studies shapes her interpretation of them. Cultural studies is a wide-ranging discipline that includes history, literature, art, and cultural expression such as folklore, all blending in a specific social context shaped by a community. This all makes challenging reading, more academic on Pearce’s part, but the stories too are rich with literary interpretation and enjoyment.

Probably the best way to approach this book is to study the paintings, come up with your own interpretations or imaginings and then read the short stories, comparing the authors’ imaginings to your own. Paintings can often evoke a variety of themes, moods, and tones, and there is no real right or wrong interpretation. Instead, art is meant to move you aesthetically and hopefully spark interpretation.

The title of the book sets its theme and captures the space in which to enjoy or study these paintings. “This book, with its focus on the Caribbean, attends to what it means to see in the dark,” says Pearce. “It considers darkness or, more specifically blackness as a critical epistemic space for seeing place and identity.” This requires some awareness of the philosophical term epistemology, which is basically determining how we know what we know. It establishes some semblance of truth in intuition or feeling that doesn’t require proof or explanation. This is what makes art unique. Black is the absence of color; “black light void” deals with space as opposed to color. The book addresses the perception of the Caribbean, which is often discussed in terms of its light.

“Black light void is a space beyond the horizon of what we already know, or think we know, beyond assumptions, stereotypes, and the taken-for granted…Black light void allows us to go the edge of our awareness,” says Pearce. She offers discussions of rhetorical and philosophical devices that offer support for art and literary enthusiasts to approach and enjoy art, which she describes as a “sensory reaction to perception.” In other words, feel free to trust your instincts. The book’s innovativeness and importance lie in the juxtaposition of visual and verbal imagery.

The short stories included explore history, folklore, personal and social awareness. They offer the reader a comparative exercise in interpreting art and also serve as an excellent opportunity for discovering Trinidadian writers. Reacting to two of Bowen’s landscape paintings as a diptych, Jenkins’s short story Hinged uses history to explore time and space. One unnamed French settler on the Spanish island of Trinidad represents the social context of French immigrants arriving after the 1783 Cedula of Population. Particularly interesting are this individual’s musings on a painting he sees. This interpretation of a painting in the past should spark readers’ conversations about Bowen’s paintings in the present. The unnamed man representing all immigrants from that period is real (in a fictional sense) and metaphorical. This, juxtaposed with a crime, offers readers contrasting images of light – arrival, hope, and promise – with the darkness of death that robs one of hope, promise, and a future.

In Foots from Westbury, Sanatan creates a story that responds to Bowen’s acrylic painting Kneel, featuring a red silhouette of a kneeling man against a backdrop of black. Using creole language, he presents a story of a young athlete exploring talent and individuality in a place where British colonialism now determines social place. In this story, as in Jenkins’s, crime is both a reality and a metaphor for stamping out promise or even personal and cultural existence.

Millar’s story and Bowen’s acrylic painting Mountain Cave, in deep blue and red, share a name. The story is inspired by the Cumaca cave tragedy in 1964 and imagines this real event through the painting. Hosein’s The Snaring of a Swan uses a fable to create a story around Bowen’s painting Totem, which features a red swan. The story of a man and woman exiled from a village for their unacceptable marriage draws on the debate over child brides featured in the case of Kumti Deopersad in 2018. This story is rich in connectivity between history, culture, and art. Pearce says Sargassum Weeds by Elizabeth Walcott-Hackshaw is a way for the author to process her grief over her father Nobel laureate Derek Walcott’s death. Using the imagery of the seaweed strangling the coast, she explores the tropical environment damaged by climate change too. The imagery of the story takes flight from Bowen’s painting North Coast Road, which features a winding road through a surrounding tapestry of landscape heading towards the coast. The story reminds us how personal art transcends the particular and becomes universal. Our interpretations stem from our own experiences. The last story, Bitter Rain by Subran, draws its inspiration from Bowen’s The Edge of the White Forest; it’s a story that questions the piety and purity of religion, set against the flashing, lightning-like tentacles emerging from an impenetrable forest.

Black Light Void, published by UK-based Hansib, is a rare, interdisciplinary reflection on art. This is a book to read and re-read, enjoy and study. The cover, one of Bowen’s paintings, is intriguing and inviting. However, the stories would benefit from a uniform layout. I always find text layouts with double spaces between paragraphs interrupt the flow of a narrative. Some stories use this layout. The afterword is followed by six pure black pages, which I find unnecessary. I prefer the black void to be metaphorical rather than real. But it’s important to see critical and aesthetic work come out of cultural studies.

Comments

"Black Light Void rare, interdisciplinary reflection on art"