Time Come: manifesto of reggae master LKJ

“If it wasn’t for reggae music I wouldn’t be sitting here today,” Linton Kwesi Johnson told his audience at last month’s Bocas LitFest, and for some of the audience that was also true, thanks to LKJ himself.

His music – a spacey dub of drum and bass, with that huge, deep, deadpan, doom-laden voice booming his verse over it – became for many young people what he described reggae as being for himself: “a crucial umbilical cord that sustained my Jamaican identity.”

For others with ties to the region, the music – including his music – was also a key to their Caribbean side. Somewhere in my mother’s attic, for instance, is a dusty, worn copy of Dread Beat and Blood, LKJ’s seminal album.

Born in Jamaica in 1952, Johnson has lived in the UK since he was 11, becoming a leader of the generation that mapped out what it meant to be black and British. For them, as he pointed out, reggae was part of the culture of resistance, in the days of the “sus” law, racist riots and Rock Against Racism campaigns. (“Sus” was short for “suspected person,” and the law meant that in British urban centres, the police could and did stop and search young men for walking, liming or simply existing while black. Its use led to race riots in British cities.)

Johnson’s career was inspired first not by music but by the American civil-rights activist WEB DuBois’ The Souls of Black Folk. Politics led him to poetry, but you couldn’t make a living from that. Hence, eventually, the music.

He listened to and was influenced by the reggae classics – Burning Spear; Toots and the Maytals; the Mighty Diamonds and no doubt the countless other three-man bands of the day; all three of the original Wailers – “everything,” he told his hearers at Bocas.

His career had begun unpromisingly, assembling filing cabinets in a factory: he had a wife and three children to support, and took what work he could get. But Johnson soon became writer in residence and librarian at London’s Keskidee Centre, the first arts centre for the black community, in north London. There he was mentored and encouraged by people like Andrew Salkey, Sam Selvon, Mervyn Morris and John La Rose.

Johnson, who had been an activist even before he went to university, was also part of the Race Today collective which produced the eponymous magazine out of Brixton, and which was influenced by CLR James.

His new book is very different from the collections of his poetry inspired by music. The discipline acquired from his degree in sociology is evident in Time Come, a compilation of his selected prose – journalistic essays, book and music reviews, profiles, introductions and lectures – stretching back to the mid-1970s.

The writing in this collection often has an academic tone (sometimes including footnotes) even when he’s writing about reggae. His references range through Miss Lou, Stuart Hall, Mutabaruka, Gordon Rohlehr, Rex Nettleford and Big Youth, among others. This is journalism at its best: informed, instant history of the times that Johnson has not only lived through but helped to shape.

From very early, he understood the importance and the seriousness of reggae, as the music of oppression and endurance, suffering and struggle. The first piece in this collection opens with a description of it by the 24-year-old LKJ – in poet mode – as “a music that is at once violent and awesome, forceful and mighty, aggressive and cathartic. It is a music that beats heavily against the walls of babylon, that the walls may come a-tumblin’ down; a music that chucks a heavy historical load that is pain that is hunger that is bitter that is blood, that is dread.”

The book usefully includes a long autobiographical essay, beginning with the song games of Johnson's early schooldays in rural Clarendon, and his first literary influences, such as his grandmother, who raised him, and who could not read, but who was steeped in Jamaican oral culture and of course knew swathes of the King James Bible by heart. He points out the parallels in other reggae musicians’ work, from that of the Wailers (Small Axe, to cite just one example) to the late Prince Far I (Psalms For I) and contemporary figures like Buju Banton.

LKJ sums up with astonishment his own literary journey to the point where he has published four books of poetry; his work is translated and taught in schools and universities; and two decades ago Penguin wanted to compile a collection of his work for its Modern Classics, making him one of only two living poets and the only black one in the series. He was suspicious at first: “I wondered,” he writes wryly, “if it was some kind of plot to undermine my street cred.”

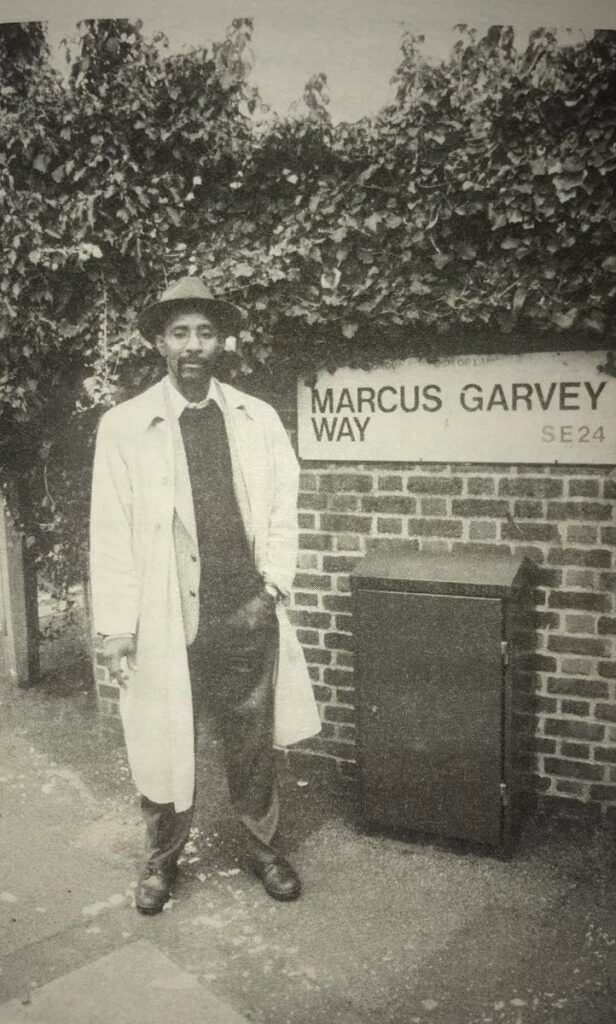

But the book, Mi Revalueshanary Fren, was duly published; and looking at him now, a pillar of the black British establishment, graced recently with an honorary doctorate from UWI, it’s hard to believe that LKJ, in his trademark suit and hat, was a figurehead of rebel music. (He adopted much of the philosophy of Rastafarianism, but couldn’t grow locks or accept the divinity of Haile Selassie or the merits of the argument for repatriation to Africa.)

His path towards poetry is traced as he recalls conversations with Selvon – himself a revalueshanary in his use of Caribbean English – who convinced the young Johnson that his lack of formal training gave him the freedom to be original. Music was central to LKJ’s work: “I heard music in language and I wanted to write word-music, verse anchored by the one-drop beat of reggae with metre measured by the bass line or a drum pattern. I wanted to write lines that sound like a bass line or a drum pattern.”

In writing about the work of others, LKJ invented the phrase “dub poetry,” and perfectly encapsulates the insanely brilliant producer Lee “Scratch” Perry as the “Salvador Dali of reggae.” Some of the performers he writes about were shooting stars at the time when he wrote about them; they flashed across the skies and vanished, and will be unfamiliar to some readers (Dillinger, anyone? Tapper Zukie?). In a 2005 essay he explains the enduring importance of Mikey Smith (Mi Cyaan Believe It), stoned to death in 1983, before he had even turned 30, for the crime of heckling a politician, in a period when Jamaican politics was at its most overheated.

The changes in Bob Marley’s work are generously discussed in the light of Chris Blackwell and Island Music’s campaign for “international reggae,” which produced music that was more palatable to a western audience and made Marley himself, as Johnson notes, synonymous with reggae for many non-Caribbean listeners. At one point, however, LKJ condemns the “contrivance and…vulgar eclecticism, mingling reggae, rock and soul…” that made Marley and others “the vogue among rock and pop stars and white middle-class trendies.” He concedes, nevertheless, after close analysis, that Exodus was a fine album.

He’s rightly critical of some of Peter Tosh’s work, such as Legalise It, while appreciating the “enchantment” of Bunny Wailer’s Blackheart Man. I’d have liked to read more on the equally towering figure of Burning Spear, though, especially as the parallels between their music seem closer than LKJ’s work is to the Marley of Exodus and thereafter.

Even when writing music reviews, Johnson sets that music in the social and political context of its times: the rise of reggae itself is part of Jamaica’s long fight for freedom. The history and politics of modern-day black Britain is here, too: this is cultural criticism, not just record reviews.

Onstage at Bocas, Johnson was warm, funny and relaxed. Asked about today’s reggae, he said he didn’t listen to it and can’t understand it. But despite the parlous state of Britain today – and contrary to his own classic Inglan is a Bitch of 1980 – he’s optimistic for the black community, saying he couldn’t understand people who said nothing had changed since the days he was writing about in Time Come.

On what the future holds for himself, he was less upbeat, calling the book his swan song. But in his essay on his career, he wrote: “At the dawn of the new millennium, with my 50th birthday looming, looking back on my life with feelings of nostalgia, I consoled myself by staking stock of my modest achievements as a reggae artist and kept melancholy at bay.”

As well he might. His “modest achievements” by then included a 25-year career and record sales in seven digits; and over 20 years later, LKJ is still with us, articulate, clearsighted and revalueshanary as ever.

Comments

"Time Come: manifesto of reggae master LKJ"