Kevin Adonis Browne's object essays: Reflections on people, places, life

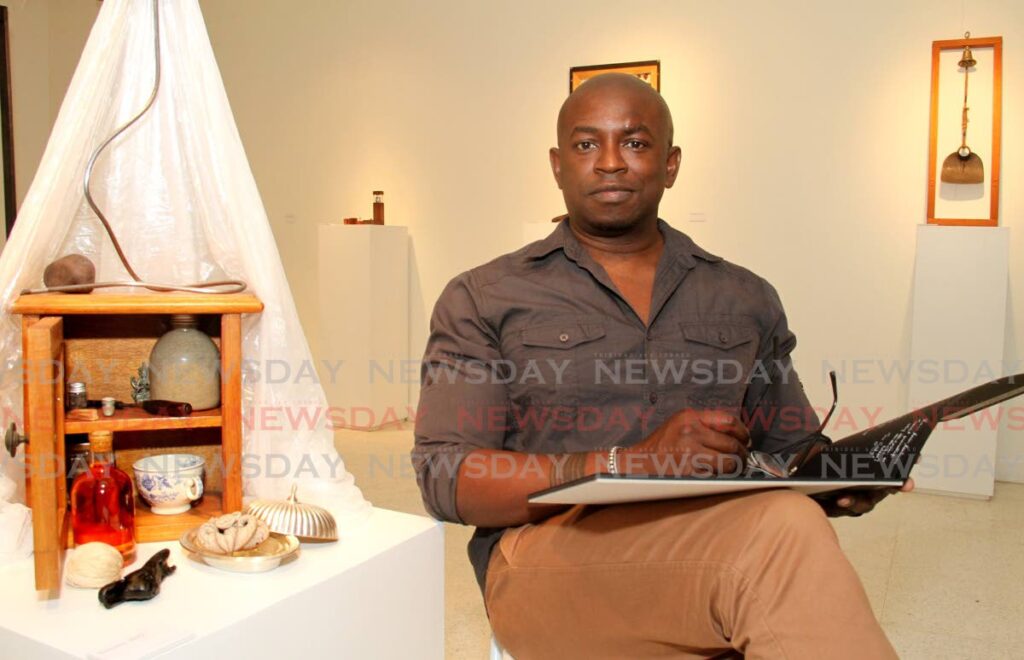

Kevin Adonis Browne is known for his photography, videography and writing. But for his fourth exhibition, he is using objects to reflect his inner self, and the people and places that affected him and his life.

In A Sense of Arrival: An Exhibition of Essays, at Medulla Gallery, Woodbrook, he is showing how much he values their memories.

One of Browne's earlier books, High Mas: Carnival and the Poetics of Caribbean Culture. A hybrid of essays, memoir and photography, won the OCM Bocas Prize for Caribbean Literature in 2019. It was the first non-fiction book to win the overall prize.

This exhibition contains 30 pieces he calls essays.

“The essence of an essay is the art of wondering and wandering – the art of exploration.”

He says in school, students are taught an essay is supposed to deal with a single subject, have a structure – an introduction, body and conclusion – and a point.

“I am deliberately resisting that. And not just resisting, but deliberately producing work that transcends that...there are no paragraphs here.”

He said he is asking people to feel rather than to think about the pieces, so that they become more about the individual’s ability to interpret and make meaning than the artist’s intentions.

He tried to express beauty, aspiration, peace, expansiveness, strength, power and depth, but there are also references to the Caribbean’s violent history. The pieces include elements such as a pitchfork, hoe, pickaxe, nails, hammer, and bottles, placed “in conversation” with each other.

“You coming in and observing these works, conversing with them in different ways, produces another layer of meaning. So your presence elevates the works. They provide a trigger or portal or platform for you to do this kind of wondering.”

There is also a theme of embedding things in the essays, including salt, sugar, hair from his family members, pieces of San Fernando Hill, his wedding ring, lines of text and blades.

“Arrival, for myself, is about me doing the work of coming into being, producing work that has been on a certain trajectory – not just academic work, but intellectual and artistic work – to understand myself...

“Not just for my own personal gain or pleasure, but to understand my people – my Caribbean people, my Trinidadian people, black people. To think about blackness not just as a simplistic beauty, but a very complicated, multifaceted and multidimensional beauty, something that transcends the limitations of violence and pain and degradation. Something that goes far beyond what other people’s expectations are of our blackness.”

He pointed out that he understands blackness from a Caribbean perspective, where blackness is taken for granted, and not analysed or deconstructed. Unfortunately, he said, this also means black people can easily be persuaded there is something wrong with being black, or convinced of someone else’s meaning of blackness. But it's a great benefit as well.

"We’re not thinking of blackness as a handicap, not from a place of critique or violence or hurt or suffering or trauma, but from a position of personal and communal power, sensibility, responsibility, creativity, beauty, profundity – something that now transcends the limitations of race, racism and ethnic strife.”

For example, he said his grandmother was the first person to call him “black boy,” so his connection to being black was rooted in her love for him.

To understand himself, he had to move beyond what he and others presumed “blackness” meant and trying to validate it.

Instead, he said, he is making his blackness take up space and making space for others – space for more conversation, interpretation, arguments and understanding.

Several of Browne’s pieces uses projector parts as a commentary on vision, revision, surveillance and how perspectives develop. It also expresses his anxieties about losing his sight, especially as a photographer.

Compounding that worry, in making several of his essays, he exposed himself to chemicals that got into his eyes and lungs and physically affected him. For example, in making the headboard called Textus, even though he wore a mask, the fumes, wood shavings and dust he inhaled while treating and sanding the wood affected his lungs.

“It also affected my reflections on death, creativity and creation, because while the headboard in some ways evokes rest, ironically it could also have been a casket I was making."

So it invites thinking about mortality.

"You could either be terrified of it, or you could embrace it and accept the fact you’re not here forever, and that what you do has meaning in the time that you’re here, and your work could transcend and outlive you, so you better do the best you can.”

Yemaya – Yoruba goddess of the sea – is a small wooden cabinet containing articles such as salt, hair, sea sand, a miniature Mother Lakshmi idol, driftwood, a hot comb and a plastic sheet.

It is a homage to Derek Walcott’s poem The Sea is History, which begins: "Where are your monuments, your battles, martyrs?/Where is your tribal memory? Sirs,/in that grey vault. The sea. The sea/has locked them up."

Since Yemaya is a goddess, he wanted to represent conceptions of natural beauty and self-care, such as the hot comb and the bois canot leaf, which, when crushed, can be used as a soap. The plastic and the driftwood coloured black to represent oil spills speak to nature and the gods being threatened by human carelessness, which contradicts the sublime.

“Care means we need to care for the environment as well...that we have not is why you see so much plastic in the sea, coastal degradation and pollution."

Despite "how beautiful and glorious and powerful certain deities are in all our cultures," he points out, man-made situations often counteract their powers.

Caroni and Sola are homages to his grandparents. His grandfather drove trucks and tractors at sugar estates in Caroni; the blades and dark wood suggest the blades that cut the cane and the tracks of the vehicles. But the viewer could also see a horned blue devil.

His grandmother, family matriarch on his father’s side, is represented by a wire-cutter with a halo made from a spiked silver bracelet from a local jewellery store and wire circling a sewing-machine adjustment ring.

He had been struggling with ways to honour her memory in art since her death in 2004, since there were no good photographs of her.

“These pieces – grandfather's tools she was not afraid to wield, the filter and frame for my own seeing and unseeing of her memory, the variegated fibres of the varnished wood, the sound of her voice represented as light, and light materially represented as objects – do some of that work for me."

It's an admission, too.

"I admit to falling short of expressing what she truly meant to me and the rest of my family.”

It could also be interpreted as a La Diablesse, with its one hoof and a ball of fire (usually associated with the soucouyant), since one handle of the wire-cutter has a cleft to remove nails and there is a halo crowning it.

“Our interpretations are evolving as we listen to each other talk about it. It’s not a question of persuasion, but...understanding... You now are in conversation with and are able to talk with and to.”

For Conscientia, he used an image of 14-year-old Luisa Calderón, a "mulatto," who was ordered to be tortured by Thomas Picton, Trinidad's first British governor, using a method called picketing. She was suspended by a rope tied to one hand, and one foot balanced on a stake. In the picture, the torturer is a person of colour.

“There is us as the witness to that brutality, but also...the oppressor and the torturer."

The piece shows "my awareness of my complicity in things like torture. I wasn’t there in 1801, but what does my silence do in 2022? What does my inaction yield? What harm do I cause or can cause or have caused as a result of my inaction – witnessing, seeing and not saying anything because, ‘It’s not my business?’”

The "essays" in this exhibition are a prequel to his yet-unpublished book with the working title A Sense of Arrival: Essays, which will also include written essays, which “focus on memoir and use words, images and objects to theorise and practise Caribbean nonfiction.”

Browne explained even his written essays were not traditional: he experiments, using a writing voice he's rarely used before.

“It is my arrival at a certain way of writing, a certain way of seeing, a certain way of thinking, and thinking that plays back on to seeing, and seeing that then influences writing."

This form of expression was “necessitated, I think, by the reality that as Caribbean people we're too complex to have just one medium to tell our story.”

He said it could be due to his inability to tell the story in just one medium but he believes to get a sense of something or someone, it has to be viewed in different ways.

So for the first time he worked with physical objects. He made things that caused his body pain and did things that made his body move, because the book demanded it, since he was thinking about his body and his physicality. He then photographed them and put them in the book, but they exist in the physical world.

Browne told Sunday Newsday he had been “playing around” with objects for years, but started producing the collection four years ago.

“I was trained as an academic, but my resistance to that training is part of what has led to my photographic work, to my artistic work here.”

Browne is an associate professor of rhetoric and writing at Syracuse University, New York State.

He grew up on San Fernando Hill, and attended San Fernando Boys' RC School and Presentation College. After Form 5, he moved to New York to live with his mother.

He joined the Marine Corps but failed bootcamp, so attended Medgar Evers College as a non-degree student before transferring to New York University to study English, and dropping out.

He wrote a chapbook of poetry, performed spoken word, wrote a one-person play, and did odd jobs.

His former professor at Medgar Evers, Trinidadian writer Dr Elizabeth Nunez, invited him to see Derek Walcott and Trinidadian author Carole Boyce Davies read.

“After the reading she said, ‘Kevin, you need to go back to college, because you need to be able to have these conversations.’”

So in 2003, he became the first graduate in the English department with a bachelor’s degree at Medgar Evers. At Pennsylvania State University, he got a masters in rhetorical studies in 2006, and a PhD in English with a concentration on rhetorical studies in 2009.

“I was always interested in language but I was also interested in trying to figure out the most effective and most beautiful way to express something.

“I always valued my own language. I've been using my Caribbean vernacular in conjunction with standardised forms for my entire writing life."

Grad school, he said, was just a place that helped him "validate what I've been doing my entire life, which is to say what my grandmother, my mother, my dad, people in my family, my community, even now, continue to do.”

A Sense of Arrival: An Exhibition of Essays will be on show until November 14 at Medulla Art Gallery in Woodbrook.

Comments

"Kevin Adonis Browne’s object essays: Reflections on people, places, life"