Kaepernick’s story: Standing tall, taking the knee

COLIN Kaepernick’s best sport is actually baseball, but that’s one of the least surprising things to be learned from Colin in Black and White, the just-released Netflix “limited series” that tells the story of his early years.

He was pretty good at basketball too, but it was American football that was his passion and that eventually became his career.

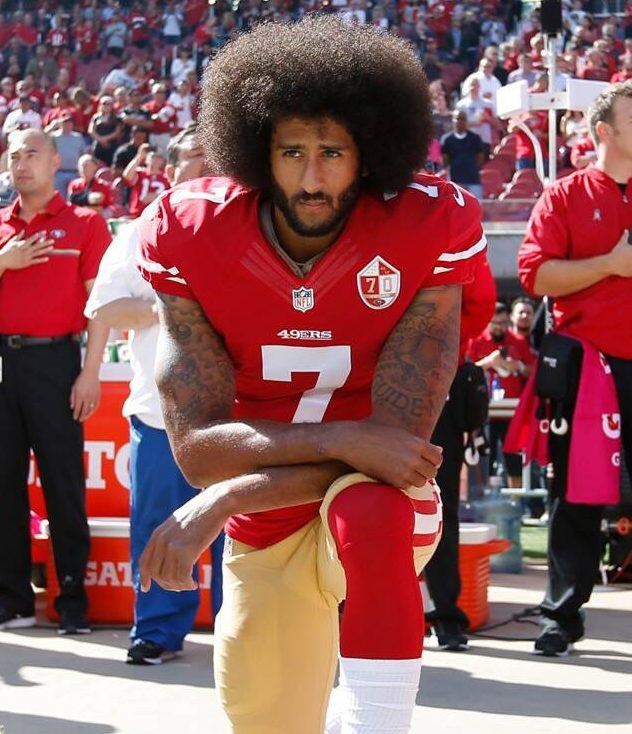

But five years after he took the knee during the US national anthem before a game, to protest racial injustice, it’s not his sporting abilities for which Colin Kaepernick will be remembered.

That’s why this series is compelling viewing for anyone, not just sports fans (before hearing his account of the role and importance of quarterbacks, I didn’t have a clue what they did or why they mattered).

Kaepernick’s team, the San Francisco 49ers, let him go after the 2016 season, apparently for political rather than sporting reasons. Since then, he’s been trying to get back into the game (which some see as a problematic move in some respects, in light of what he says in this series). He still trains for five or six days a week, in preparation for the call.

But most of his time and energy goes into activism, and now he’s teamed up with leading director Ava Du Vernay (best known for Selma and When They See Us) on this series, a mix of drama and documentary – or polemic. So it gets two bites at the cherry, very different, but both worth seeing.

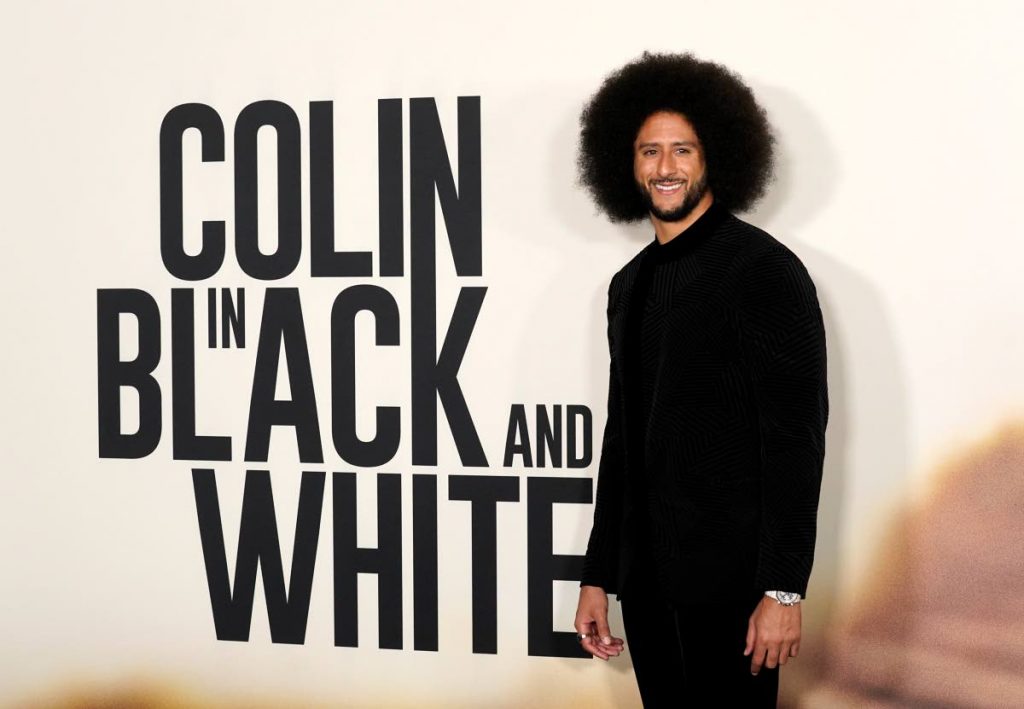

It opens with a close-up of that solemn Old-Testament-prophet face, framed by what has become his trademark cloud of an Afro, its vast softness contrasting with his bony features (Kaepernick often looks much older than his 34 years), as he speaks directly into the camera.

He does this many times: he has the conviction and charisma to keep you watching as he sits on a concrete bench or paces around a bare grey room. The dramatised scenes are sometimes projected on the back wall. Characters from the drama walk into the room, or he walks into their scene, breaking the “fourth wall” of theatre tradition. This technique makes for a staccato mix of episodes from his youth, historical vignettes and lectures from the adult Kaepernick, but it works.

For one thing, it shows how far he’s come. The teenage Colin, engagingly played by Jaden Michael, lives in California with his white adoptive parents (Mary-Louise Parker and Nick Offerman), who back his sporting ambitions, but who by today’s standards are startlingly blind to the issues raised by a mixed-race adoption.

So is the young Colin. He’s protected by the middle-class privilege his parents bestow on him, but unlike them, he experiences countless racial microaggressions, a word and a concept he didn’t understand then and which his parents simply did not see. When they drive him all over California to baseball games, there’s no problem; when Colin drives, he gets pulled over by a suspicious, jumpy cop. Coaches put him through harsher tests than other players (“Why am I always the one who has to prove them wrong?” he wonders) – although you get the feeling that’s not just a matter of racism: the gangly, quiet young Kaepernick may comply, but he’s testing them in return.

Occasionally there’s a family clash whose cause seems like normal teenage surliness, but it’s complicated by the Kaepernicks’ being open-minded enough to raise a black child – but trying to raise him as if he were white. They’re disturbed when, at 14, Colin decides to get his hair done in cornrows, like his hero, the basketballer Allen Iverson; but it’s braided too tightly, by a young girl who says “biracial” hair is hard to handle. His mother clumsily asks two black colleagues where she can get her son’s hair cornrowed properly, and he’s thrilled – yet months later, his parents flip-flop again, siding with his basketball coach when he invents a rule that Colin must cut his hair to stay on the team.

These scenes are punctuated by the adult Kaepernick’s passionate but controlled and sometimes even wryly humorous interjections on moments from black history or modern life (at some point, American racism has turned him from a “biracial” teenager into a black man; as in the series’ title, in the US there are rarely any shades between black and white). He quotes WEB Du Bois; he tells his audience that twice as many black as white mortgage applicants are turned down; there’s a scene, complete with unconvincing accents, that relates the invention of hip hop by the young Jamaican who became DJ Kool Herc. He invokes Steve Biko, Marcus Garvey, Huey Newton, Toni Morrison. There’s a clip of Nina Simone, during a whole episode included to make a point about ethnicity-based ideas of beauty and “shadism.”

Eventually all these elements coalesce into the conscious political philosophy that led Kaepernick to kneel for the anthem. In relating examples and consequences of racism, he declares, “Some say the system is broken. I’m here to tell you it was intentionally built this way.”

Very early on, describing the undignified scrutiny to which would-be professional footballers are subjected – poked and prodded, put through their paces, their armspan measured – Kaepernick compares it with a slave auction. That’s pushing it: enslaved people didn’t get to choose whether to be auctioned, and they weren’t paid millions of dollars if they passed this nonconsensual physical examination.

Explaining the acquiescence of footballers, he observes, “You’re not thinking you’re being groomed…you just love football.” But his story shows it’s much more than just a game, and illustrates the (originally feminist) adage that the personal is political.

Kaepernick also makes the point that very often racism makes it hard for black people to get a job that pays a living wage. He doesn’t take the next logical step – that itself is one reason why so many young black men are desperate to become professional athletes.

His denunciation of the system might make it hard to reconcile his condemnation of the “slave auction” for footballers with his love of the pro game that made him a multi-millionaire; except that as he says, being a quarterback was “all I ever wanted, it’s in my blood.” Even now he would put on his helmet and run back onto the field, if the price were right: is that mercenary, or an insistence on being paid what he believes he deserves?

The young Colin was far more naïve, but the scenes from his life also demonstrate his unshakeable sureness of his own ability and the persistence that kept him going when he was persecuted and abused for taking the knee.

A large part of the six episodes of the series is devoted to his brilliant school baseball performances and his determination nevertheless to be a quarterback; it was his heart, not his head, that made that choice, and he can only finally explain it by saying he felt like a “visitor” in baseball.

Shedding light on this feeling is a re-enactment from the life of Romare Bearden, the baseball player who was offered a place by the Philadelphia Athletics, where he would have been the first black member of a Major League team – if, by this account (sources conflict) he were willing to pass for white. Bearden said no, and eventually became a successful artist.

With these examples, and those from his own experience, the series is leading inexorably to the point where Kaepernick has the consciousness and the courage needed for the apparently simple, respectful act of taking the knee, a gesture now both endlessly vilified and emulated.

That move left him, so far, no longer a quarterback. But it’s brought him the kind of fame he must always have dreamed of – if not for the reason he imagined on the school football fields and pitcher’s mounds of his boyhood.

Comments

"Kaepernick’s story: Standing tall, taking the knee"