David Diop exposes horrors of war, racism in new book

I loathe books with gratuitous sex or violence. It is a cheap way to lure readers into weak stories.

But I stomached the horrific violence in At Night All Blood Is Black by David Diop because it proved necessary to expose the horrors of war, colonialism, and racism. Diop uses violence to touch raw nerves, and in the process, penetrates the culture of prejudice that prevails as a colonial legacy.

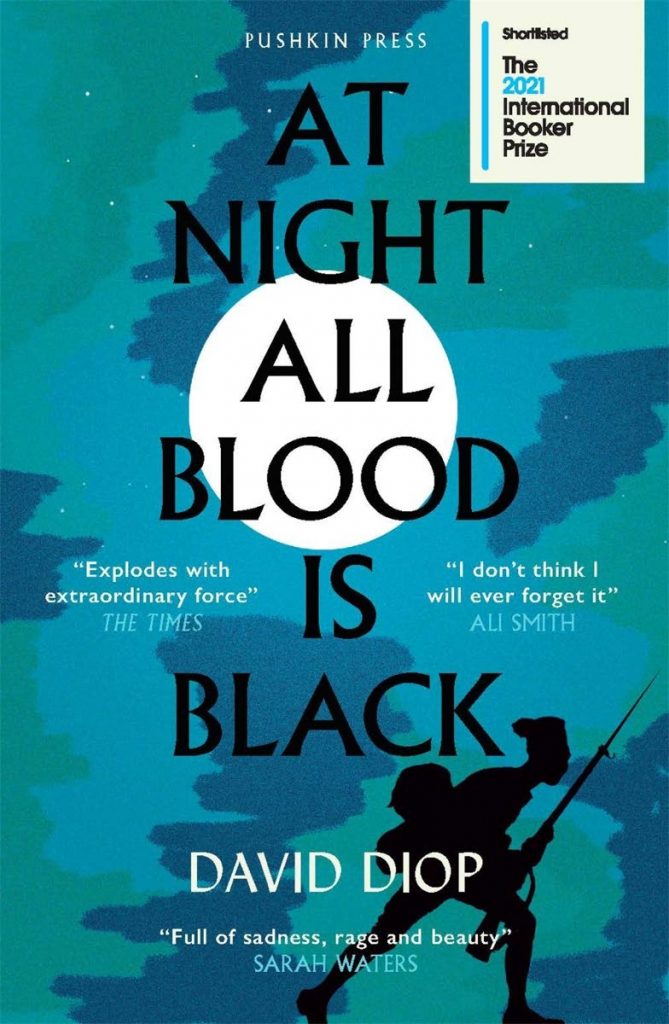

Named as the 2021 Booker Prize, At Night… translated by Anna Moschovakis, is the first French novel to win the prestigious literary prize.

Diop’s background provides the ability to straddle both European and African culture with equal understanding. Born in Paris in 1966, he grew up in Senegal. He now lives in France and is a professor of eighteenth-century literature at the University of Pau.

At Night All Blood is Black is a historical novel with timeless themes of friendship, duty, honour, and guilt. Set in the French trenches of World War I, the novel tells the story of Alfa Ndiaye, a Senegalese soldier, simple, honourable and obedient. He has never left his village before he joins the army, in a naively patriotic gesture, to serve France.

Lucid and eerily unemotional, Ndiaye begins his story by telling readers that in the world before the war, he would never have committed the atrocities that came to define him as a soldier.

Tension in this short novel of 160 pages arises from the first sentence, “…I know, I understand, I shouldn’t have done it,” Diop writes. Thankfully, he apparently realised readers could not have survived a longer version of this gut-wrenching novel, described by the UK Guardian as “heartbreaking and poetic.”

The Senegalese soldiers in the French army soon experience unexpected prejudice. Distinguished by their skin colour and marginalised by their African culture, they are called chocolat by the other French soldiers.

With sickening, graphic description, Diop shows readers the scene that turned a simple African villager into a revenge-driven murderer, who transcends the boundaries of decency even in war. Ndiaye tells us that his transformation began because his “brother,” Mademba Diop, “took too long to die” in No Man’s Land, that area that divides two enemies. This No Man’s Land becomes an apt metaphor for the place that Ndiaye occupies in his mind after the fateful day he dies.

Ambushed by a German soldier who had pretended to be dead, Diop is fatally injured when the German’s bayonet disembowels him. Still alive, Diop begs Ndiaye to slit his throat so he doesn’t suffer there in No Man’s Land.

The description of the two soldiers’ agony, both physically and mentally, crosses all emotional boundaries. Without giving away details that readers should experience, suffice it to say that Ndiaye’s decision regarding Diop’s request leaves Ndiaye tormented and guilty.

Diop’s death propels Ndiaye into violence that at first glance seems acceptable. Caring nothing for his own survival, he continually crosses No Man’s Land in the dead of night, sneaks behind enemy lines and brutally kills enemy soldiers. He returns to his trench with “trophies” that delight the French soldiers and earn their respect.

Initially, they hail Ndiaye as a hero. He is revered for his bravery. The cultural disconnect between the French soldiers and Ndiaye prevent them from understanding his motives.

“Home with my trophies, I saw they were very, very pleased with me. They saved food for me, they saved bits of tobacco. They were so pleased to see me come back that they never asked me how I did it, how I captured the enemy rifle…” (and other unspeakable acts that may be too graphic for a review).

Clearly, Ndiaye has not lost his mind. He chronicles his descent into revenge and violence with dispassionate clarity.

“When I leave the belly of the earth, I am inhuman by choice,” he says. “I become a little inhuman. Not because the captain commanded me to, but because I have thought it and willed it.”

Soon Ndiaye’s acts worry the commanders, who recognise that they are violating conventions of war. The other soldiers become uncomfortable when they realise Ndiaye has no intention of ever returning to them as a “normal” soldier.

Eventually they wonder how Ndiaye constantly defies the odds and survives these solitary excursions to kill Germans. Tapping into their prejudice, they finally relegate Ndiaye to a practitioner of African witchcraft. The French soldiers begin to fear and scorn him.

At Night All Blood is Black has been garnering literary awards all over the world, among them The Los Angeles Times Book Prize for Fiction, and the Strega European Prize in Italy. The novel was elected by students across France to win the Prix Goncourt des Lycéens. Many newspapers in the US and England named it one of the top 15 books of the year. Ali Smith wrote in the UK Guardian that the novel is "So incantatory and visceral I don’t think I’ll ever forget it."

It is a haunting novel.

My only issue with it is Diop’s inclusion of Ndiaye’s village life late in the novel. I am not sure that readers, rooted in that trench, need to travel back to Ndiaye’s village. Some flashbacks woven into the war story might have sufficed for background information, or perhaps just allowing the reader to imagine what Ndiaye’s life was like before the horrors of war, might have worked. Structurally though, as it is, the anecdotes of Ndiaye’s past are important, but anticlimactic.

At Night All Blood is Black is David Diop’s second novel and is currently being translated into 13 languages. It is a multi-layered story that transcends time and boundaries and speaks to all of us about prejudice and colonial injustice. It is, as most reviewers claim, unforgettable. Ask your favourite bookstore to order it, or it can be ordered on amazon.com.

Comments

"David Diop exposes horrors of war, racism in new book"