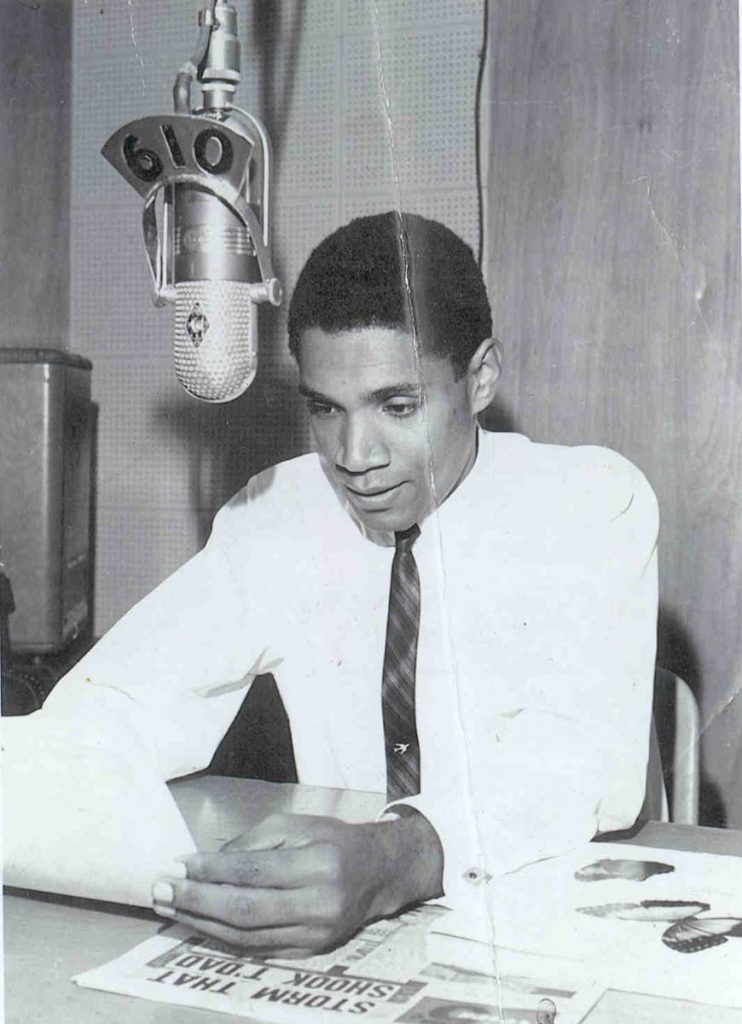

Jones P Madeira, reluctant hero of July 1990

JANELLE DE SOUZA concludes a special series on veteran journalist Jones P Madeira with his experience of the 1990 attempted coup, when as TTT head of news he became the voice of calm for the nation.

Friday July 27, 1990 began like any other ordinary Friday for Jones P Madeira.

As head of news and current affairs at TT Television (TTT) on Maraval Road in Newtown, he launched a training programme for television cameramen; had a business lunch; took his daughters shopping in Port of Spain, as it was the last day of the school term; checked in on the two German videographers facilitating the staff training; held a production meeting; and continued to prepare for a trip to Kingston, Jamaica the following morning for a meeting of the Caribbean heads of government.

As he got down to editing, someone rushed in saying there had been an explosion at police headquarters downtown, so he sent people out to cover the incident. He thought it was an isolated event and never thought it was linked to demonstrations that had been taking place for improved governance, against unemployment, discrimination, and other issues, over the previous few weeks.

“Even with that, we did not anticipate what was to come. There was no indication in the public domain. Everything started to happen alongside the other.”

He was in the editing suite, a small booth with a single glass full of equipment, editing a story for the nightly Panorama news programme, when events started to unfold. He and everyone else, including journalist Raoul Pantin, were busy because they wanted to finish pre-air production by 6.30 pm. While there he was notified that people were “running around” in Port of Spain, but he could not think of a reason, because there were no demonstrations scheduled for that day.

“While I’m contemplating that, I heard what sounded like gunshots outside of the building. The noise was so loud. It was a bit confusing. And then the noise came closer and I said, ‘This is nonsense. I have to talk to the management about putting some protocols in place to prevent this kind of noise,’ which many a time interfered with our own audio.”

At that point he turned around and, through the window, he saw a man pointing a gun at his head.

“When I saw him I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. I thought it was a game.”

But when he looked into the man’s eyes, he realised it was no joke. The man shouted at the nearby staff to “tell that man to get out of there.” He thought it was a vagrant who had found a gun and “went crazy,” so he ducked and crouched under the window and – cliché or not – the highlights of his life passed before his eyes.

He decided to face the situation. He opened the door of the booth and an armed man grabbed him and took him out of the room. He saw other employees with their hands in the air being pushed into a common area – but he still had no idea what was happening, or that the Parliament had been taken over as, at that time, there were no cellphones or social media.

Madeira recalls the men were saying things like, “Y’all thought we were making joke all along. We taking over this damn country! Too many things going wrong. Put your hands on your heads or we’ll blow your heads off!”

He had no idea who they were but figured they were a faction of the demonstrators, and he was correct as the Jamaat al Muslimeen was part of the Summit of People’s Organisation, which had been at the forefront of the demonstrations.

The other option, to his mind, was that they were members of the army because, after being ordered to lie on the ground, he noticed their army boots.

But he got his first major hint when they began to shout praises to Allah.

The staff were then moved to the lobby area and there he saw leader of the Jamaat, Yasin Abu Bakr, walking out of the studio with his hands on presenter Hazel Ward-Redman, "Aunty Hazel," who had been taping a children’s programme.

He said Bakr was startled to see him, but then approached him to say the Jamaat had taken over the country and wanted to announce it to the population. He told Madeira they had then Prime Minister ANR Robinson under arrest and if Madeira kept everyone calm, everything would be all right.

Madeira got to work trying to reassure traumatised staff members when he noticed other Jamaat members he knew, including one who sold small items during regular visits to staff at the station and another who tuned out to have been a schoolmate at Holy Cross College in Arima.

Madeira also got the Muslimeen to agree to release several people, including women, children, the two Germans, and eventually an employee who suffered from lupus and needed food and medication.

“It was clear that I had a role to play from the word go, because Abu Bakr started to refer to me for everything that was going on.”

He was also afraid people would be hiding and that members of the Jamaat might stumble upon them and shoot them by mistake. Someone suggested he make an address on the public address system, and he told the staff to come out of hiding and encouraged them to keep calm.

The Muslimeen marched Madeira into the main studio. They wanted him to announce on air that the government had fallen, the PM and his Cabinet were under arrest, they had taken over the country and they wanted to talk about having an interim government.

Even then Madeira’s journalistic ethics came into play. He did not know if what Bakr was saying was true, and he did not want to scare the public. He voiced his dilemma to the group, which upset some of them.

“That got one of the fellas so vex. He took out his revolver and said, ‘You think it’s joke we making?’ He was becoming agitated.

"I don’t think anybody realised the tremendous strain that one would be under in circumstances like that.

"Then I had to muster all the courage you could possibly think of to go and face a television camera – which is stressful in any event – to talk to the population.”

He said he did not want anyone to think he was part of the coup attempt, and wanted people to realise he did not know what was happening. So when he was put on air he faked calm as best he could and used words like, “I have been advised,” and “I have been told,” when he made the announcement.

He then introduced Bakr, “the person who says he is head of the interim government,” who then addressed the nation.

After ensuring no one was hiding in the building, the Muslimeen brought everyone to a central, and hopefully safer, location, as they anticipated that the building would be attacked by the army.

Madeira was then allowed to make phone calls,

as the Jamaat wanted to create a negotiation team. He also called home and spoke to his family.

The first person they wanted was attorney Ramesh Lawrence Maharaj, but he was out of the country. Madeira tried calling the Red House, but could not get through.

Meanwhile, the US TV station CNN had broadcast a story about a coup in TT, so by the time 7 pm rolled around, he realised what the Jamaat was saying was true.

He did a second broadcast telling people what had happened at TTT before Bakr again addressed the nation.

Someone handed Madeira a list of the names of the hostages at TTT to read so their family members would know where they were.

“People wouldn’t know it, but I found it overwhelming to do. I had to literally train my gut not to explode while making these announcements. I told myself to use my sense of humour to jazz it up and I said, ‘Oh, incidentally, just in case you didn’t make me out, I’m Jones P Madeira.’ They erupted in laughter and that made the situation lighter.”

People also started asking for food and that was supposedly arranged, but no one ever got it. The food was left in the road, because the delivery people were afraid to approach in case they were shot by the Jamaat, and the Jamaat and hostages were afraid to get it in case they were shot by the police or army.

The Jamaat said they said they did not want to harm anyone, and they would go to Madeira first to talk about any problems. And so he started to deal with people who were "shell-shocked." Madeira had never encountered guns before, so he and the staff were tense, but he tried to bolster them. Their conduct and resilience made him proud.

He was also the liaison between the staff, the defence force, the Red House, government representatives and the Jamaat.

The whole situation left him mentally and emotionally drained.

“I did not actively become involved in any negotiations. What I did was serve as the conduit between the government, (Attorney General) Selwyn Richardson (who was a hostage at the Red House) in particular, and the Muslimeen, Abu Bakr in particular. History will judge whether I handled that well. But I was thankful that at least I was able to serve in some form.”

Bakr did another broadcast on Saturday morning, which was only heard south of the Gran Couva transmitter, since the army had disabled the one in Port of Spain, on Cumberland Hill, on Friday night. But soon after, the army took control of that one as well and took TTT off the air. The army then set up a temporary broadcast facility to keep the public informed.

“That sent the Muslimeen livid. They said all sorts of things: that if it was not re-established they would not be responsible for the number of deaths that would happen. The more they spoke the more agitated they became.

"We had to draw the conclusion that at some point we would suffer great harm.”

TTT was attacked by the defence force and the police at least three times. Those inside laid low and no one was hurt but it felt as if they were in a war zone. They were traumatised – in addition to being hostages, they were ducking bullets and hearing explosions.

On Sunday, Anglican priest Canon Knolly Clarke visited with a contingent to see the conditions under which the hostages were being held and to talk to Bakr.

Bakr called Madeira into the room and told Clarke he did not want to take over, but wanted change. He also wanted to be Minister of National Security and for Winston Dookeran, then Planning Minister, to be Prime Minister. (Dookeran had not been held hostage and acted as Prime Minister during the coup attempt.)

Clarke tried to reason with Bakr, saying he would have to be elected, but Bakr told Clarke to use his influence to get it done. Clarke also tried to get Bakr to release the hostages, but Bakr refused.

There was an attack soon after Clarke left.

Madeira said from then on, the confidence in the Jamaat's makeshift “war room” started to wane.

No one had eaten for days. Tensions were high and all were alert for any sound. So for the next few days he tried to get members of the Jamaat to relax by showing them some movies.

Once, he said, as they started to watch a movie there was a machine-gun attack from outside that rattled the building. He dived to the floor and started to feel a coldness on his gut and a sound like liquid being quickly emptied from a bottle. He told the others in the room he thought he had been shot. It turned out he had fallen on an open can of Coke, which elicited much laughter.

But tensions continued to rise and on Monday or Tuesday, the younger Jamaat members started to get agitated. They wanted to know when they would be allowed to start shooting hostages. Seeing the discontent, an older member approached Madeira and encouraged him to do his best to get in touch with someone to negotiate with as quickly as possible.

Not too long after that, while he was talking another staff member through a bout of depression in a separate room, a rocket blew up the room next them. He recalled seeing the light, then hearing the explosion, which left his ears ringing for several days.

He and fellow senior journalist Raoul Pantin increased their attempts to contact various people to negotiate the hostages’ release, but they could get no one, since most of the Cabinet was being held in the Red House by the Jamaat, and no one would tell them where President Noor Hassanali was. He spoke to Chief of Defence Staff Col Joseph Theodore several times.

Pantin was becoming very tired and overwhelmed with frustration. He recalled at one point, Theodore told Pantin it was best they stayed where they were because "I am not sure what’s going to befall you if you come out here."

Madeira said Pantin was badly traumatised by the situation and never fully recovered, which he felt sad about. After the ordeal, Pantin would call him on his house phone at all hours before dawn to talk, and his personality changed.

In the meantime, negotiations were taking place at the Red House.

Then, on Wednesday, Theodore told Madeira to inform the Jamaat there would be no amnesty and they would have to surrender. Everyone in the building was to come out one by one with their hands up, and Madeira must come out first. Initially he resisted, wanting to ensure all the TTT staff were accounted for, but a few “choice” words from Theodore made him change his mind.

So he was first out of the building, and discovered just how traumatised he was.

“After all of that, I came outside with my hands down. I looked up Maraval Road and I thought, ‘My God! Look at what these people have done to my country.’ I was hearing a loudspeaker in the background but I wasn’t really paying attention.

"Eventually I realised they (soldiers) were screaming at me to put my hands on my head.”

He walked up the road to the Tatil building a few yards away, where members of the Defence Force were waiting. The hostages were put on a bus and taken to be medically examined.

“I cannot put into words what it was like driving away from that hell.”

He plans to tell his story in a book that he has begun to write. His one regret is that he did not take more notes.

Remarkably, Madeira did not have any serious side effects. He said the TTT hostages were all evaluated by a psychologist at the time and again two years later, but he did not have signs of post-traumatic stress disorder.

However, there were slight changes. Previously he would sleep with his bedroom door open but after, he would ask his wife, Melba, to keep it closed. Now he has the habit of dwelling on what bad things could happen in a situation and work out solutions so that, if something happened, he would be a step ahead. After a while, he also developed a racing heart.

At his second psych visit the psychologist said his not having negative effects was unusual, and warned him they could appear weeks, months or years later. But he is still waiting 30 years later.

He attributed his resilience to several things, including the fact that he spoke to Melba during those six days, and was assured his family was fine. Melba also went to church to pray for him every day while he was a hostage; they both believe in the power of prayer. The love and care of his family and his approach to life were also factors.

He said he understood there were people living through worse situations than he endured, he did not blame himself for anything, and he understood that everyone was different and no one would handle things in the same way.

While some people called him a hero, Madeira said his actions were not motivated by glory, and he did not want any now. He simply played the role he had to play.

Comments

"Jones P Madeira, reluctant hero of July 1990"