James Lee Wah: Culture hero from the Southland

Ken Ramchand

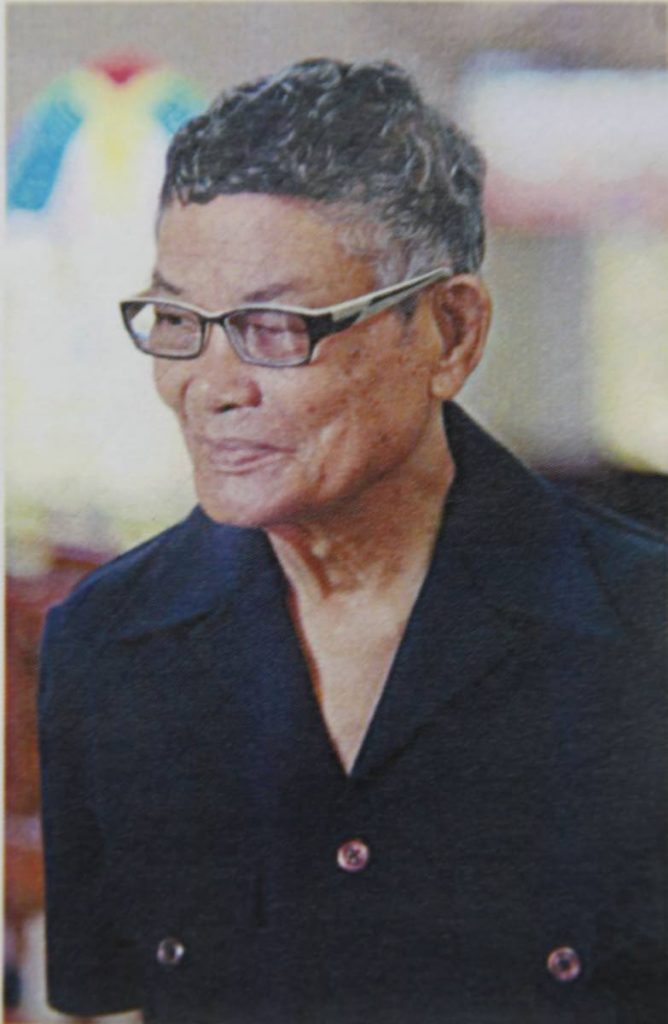

Jimmy.

A man of literature, a man of theatre, a man. Quiet, smiling, unfussy, casual; dedicated to the cause of drama and the humanities. I met him when he first came to teach at Naparima College in 1956. He had been a member of the golden generation, the first UWI people – Derek Walcott, Slade Hopkinson, Rex Nettleford, Errol Hill, Philip Sherlock, Archie Hudson-Phillips, Mavis Arscott, whom he married, Carol Dawes, artists all, bright and alive, who lit up the Mona campus and projected a West Indian nation in which the arts and humanities would make soul clap hands and sing.

I used to go to his room in the dormitory to breathe in his books and plays, and feel his calm, and his ways of giving you space to be. I knew the name Vic Reid and he lent me New Day. He introduced me to Roger Mais. I read his copies of Brother Man and The Hills Were Joyful Together.

He had distinguished himself as a producer of plays in Jamaica and he was quietly getting ready. Naparima itself wasn’t backward: in 1956, a small Shakespeare festival of excerpts from the plays was being done in the college. He took part. By 1958 he was recommending “a drama festival instead of a Shakespeare festival to allow the presentation of West Indian plays” and “from time to time”, plays prescribed for study. The change was made in 1960. He taught us A-level literature by letting us talk about the books, never telling us anything except by indirection. Sometimes he asked a question that made us re-think but not shut up. He didn’t talk much in the small HSC class. If we didn’t talk for ourselves, I don’t know what would have happened. He was the greatest of teachers because he never taught, meaning he never taught in the usual way. I don’t think he knew or cared anything about testing or student assessments and such. If you did an essay for him he talked to you about it, and never gave you back pages with scribbles that you wouldn’t bother to decipher anyway.

The majority of the boys at Naparima College were country boys (Ecclesville, Sangre Grande, Tableland, Princes Town, Cedros and Victoria Village) on the long march from the bush to the college, and to the fabled cinemas of the city. It was not a city like Port of Spain. There was no discrimination according to ethnicity or region in the the rural-urban city or in the Presbyterian College where Thornhill, Samuel, Byam, Ballah, Carl Osborne, and Lance Moore were heroes.

But few of us had ever seen a play or imagined that people like us could actually walk on the stage and feel secure enough to put ourselves into other selves. We were just what Jimmy needed. He was inspirational. He drew things out of you you never knew you had. Ask Ralph Maraj and Errol Sitahal and David Sammy. He turned Naparima College into a school of drama that instilled cultural confidence and opened up unbounded areas for personal growth and creativity.

He had a vision of San Fernando as a locus for culture and the arts that would encourage artists not to head for Port of Spain to fulfil their talent but to work in the geographical space that nurtured them and gave them their raw material. That’s the space he would work to maintain.

Beginning with the San Fernando Drama Guild founded by Horace James in 1955 and handed over to him in 1956, he spent a lifetime bringing people together in associations like the San Fernando Theatre Workshop (1976) and The San Fernando Arts Council (1969).

He dreamed of a network of small multi-purpose theatre/ cultural centres in villages all over the island, and after he formed the Secondary Schools Drama Festival Association (1965) it might have come to him that the ground for such a network was being laid.

Good things had a way of happening but he always believed you should actively help them to happen. He was convinced that drama with all the ancillary skills it encouraged should be a core activity in the schools. He found money for scholarships and training courses for teachers. He lobbied. He was more responsible than anyone else for the introduction of drama into the school curriculum.

Jimmy’s understanding of the role of the drama (“to develop the whole man”), his technical skills, and his conviction of his need to invent to make things fit his setting developed out of his involvement as a producer with a wide range of plays from many different countries – Greek classics, British, French, American and of course West Indian.

He was not narrow-minded and he had no political interest in a blanket rejection of his sound colonial education. It pleased the pioneer that the schools drama festivals brought into play for West Indian actors and readers neglected West Indian dramatic works written for voices and bodies like theirs; and that it motivated new writers and theatre people like Rawle Gibbons, Victor Edwards and Zeno Constance. He held a play-writing competition. He went out of his way to encourage the performance and the writing of Trinidadian plays.

If San Fernando was going to become a cultural base, San Fernando had to continue to exist, and when James Lee Wah saw the environmental terrorism that drove Winston des Vignes to write the poem Progress, he formed the San Fernando Citizens Action Group, just in time to save enough of San Fernando Hill and to shore up its landmark existence as a Heritage Park.

When we invited him to be an honorary distinguished fellow at the UTT he was so happy and so humble and so ready to contribute to our work. The UTT later admitted him as an honorary doctor (which we should have done in the first place.) I made sure he understood that in accepting the title he was honouring the university, that it was he who was doing the honouring.

That’s it. He honoured you, and he honoured whatever work or play he shared with you. Condolences to his son and daughters, to all his students, to his brothers and sisters in and around theatre, and to his many followers, to all of whom he was Jimmy.

Comments

"James Lee Wah: Culture hero from the Southland"