Pierrot, Road Trip explore Caribbean identity

SOMETIMES the stanzas of a poem remind us of the strips of cloth of the pierrot: their rectangular shape, their varied lengths, the way they hang in one direction. With their multiple images, colours, textures, and tones, the individual lines of a poem, too, enact this variety. Each has a different weight, though each must absorb and be absorbed into the whole.

This is a good place to start when considering how poetry often attempts to make sense of the world. A poet might seek to parse experience. Or they might array things into a mosaic purely to create a difficulty that generates pleasure. Or they might write through a process or constraint. Or all of the above.

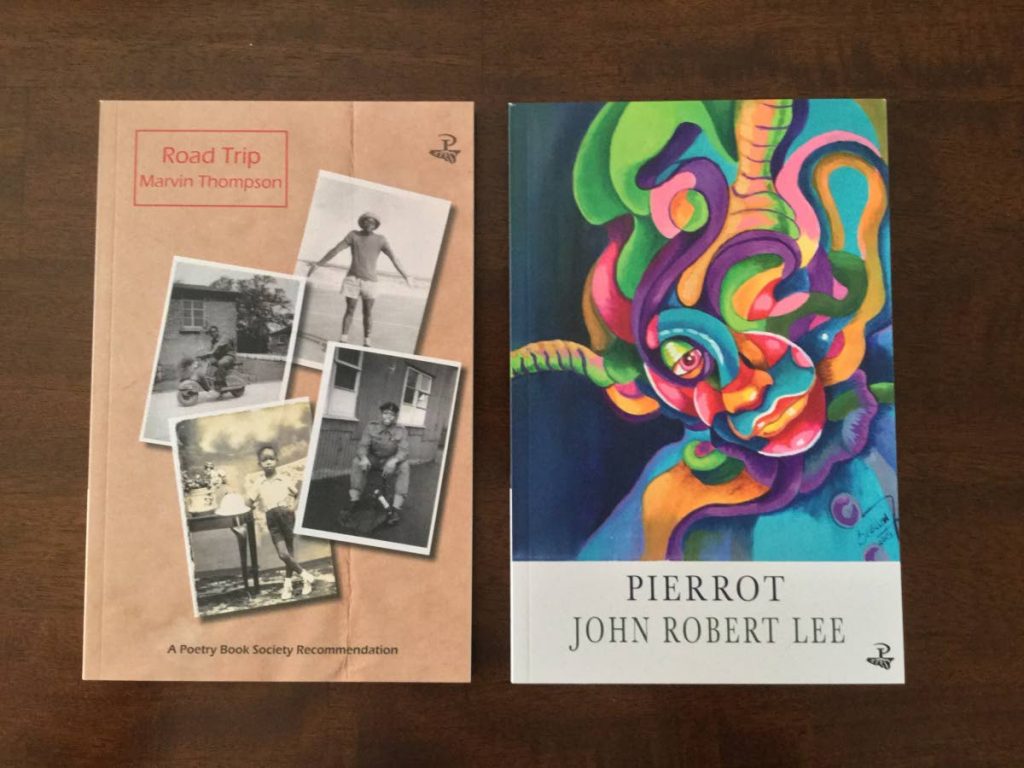

In two recent books, we discover Caribbean poets grappling with the idea of Caribbean identity in a manner that draws upon the line as a useful resource.

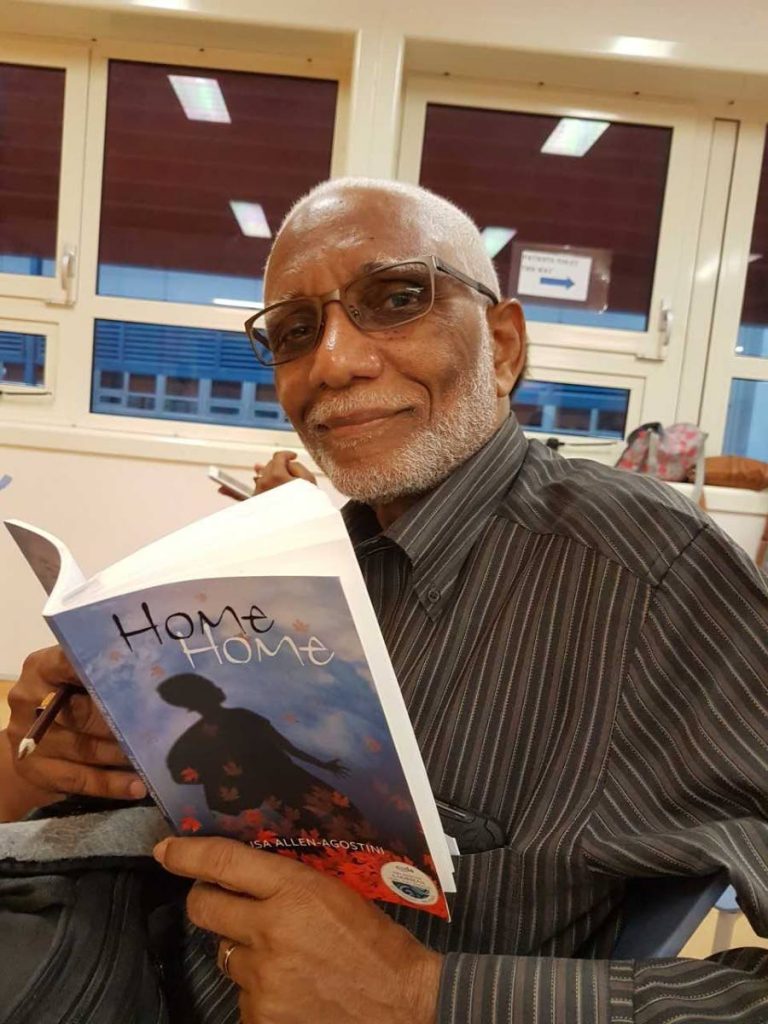

At the heart of St Lucia-born John Robert Lee’s Pierrot (for the purpose of this review we need not consider the differences between the pierrot and the pierrot grenade, though the poet shows awareness of this) is the idea of art inspiring art. Here is a book in dialogue with painting, with sculpture, with photography, with music, with writing. This alone makes us pause, question what is art and how it relates to posited things and the ever-changing world. “Some would say all poetry is ekphrastic,” the poet muses.

The cloth is cut from poets and their poems too. The first half of the book features pieces that deploy a form known as the glosa, in which the poet inserts lines between those of another poet’s four-line stanza. Here, the stanzas are taken from figures like Derek Walcott, Dionne Brand and Francis Thompson, as well as the Psalms.

A glosa stanza normally swells to ten lines, but John Robert Lee breaks these into smaller tercets or units, and inserts section headings that cut into and weave them. This creates the sense of the reader becoming implicated in crossings and transgressions. The stanzas themselves sprawl across the page, billowing from right to left, left to right. The energy overspills even when these glosa variations are not deployed: the epigraphs in other poems carry more weight given the book’s ecology.

The deployment of these manoeuvres fits the mélange of the Caribbean; mirrors its cosmopolitan nature and history; reveals the pierrot the poet has in mind – a political personification of a region that is contradictory. Side by side they stand: the wise and the foolish, the ugly and the beautiful, the promising and the doomed, the sacred and the profane. This is a writer concerned with “the collage of Atlantic surf,” the “Caribbean vernacular” and “ossuaries, yes, of failed states and their politricks.”

Poems, despite their artifice, also produce moments that feel candid. Here, the poet confronts aging with an elegiac tone, observing, “Much has gone” and “I draw near the highplace.” In Haiku: at 70, there’s a matter-of-factness to the scene, the speaker sits among “books, memorabilia/unused plates, termites”, and the poem, near the centre of the book, is placed on the centre of the page. We must all turn.”

Later, we encounter this lament: “too few reviews/and fewer paid invitations to read my poems of faith." This, and the gesture to Thompson (of The Hound of Heaven fame) opens contemplation of the relationship between faith and poetry, be it through figures like St John of the Cross, Gerard Manley Hopkins or simply the enduring influence of biblical text on verse (evident here: “ziggurats of Babylon”).

As if voyaging down the labyrinthine ways of the poet’s mind, these reflections are juxtaposed with a newsreel technique, the poems roving across the margent of the world, touching things such as the tragedy of Aleppo, racist killings, deaths of celebrities and various scenes in London. A speaker asks: “Who made my skin a boundary?”

Overall, there is a transformation that, if not celebratory, runs against the tide. So the Mighty Shadow, who wore all black as he sang against the cultural hegemony of the colonial, is re-born in these rich, reflective pages as a “prancing pierrot.”

Whereas pierrot’s lines sprawl across the page, Marvin Thompson’s tumble like a waterfall. In Road Trip, a stunning, unforgettable book with a strong sense of place, some of the best moments come from how the poet, who lives in Wales but was born in London to Jamaican parents, deploys skeltonic verse of increasing intensity. The opening lines are short, just a few syllables, and paired. But the deeper we go, the more echoes and rhymes begin to emerge, as though the accretion of musical experience itself. Call it jazz.

Like Lee, Thompson is concerned with the Caribbean self, but from the perspective of someone on the other side of the Atlantic. For this poet, it is the loss of a father, something which hurts particularly at Christmas time, that is the beginning of his inquiry.

As is the case in Dylan Thomas’s wonderful Christmas broadcast, Memories of Christmas, Thompson sets the scene for but does not deliver a trite, sentimental yarn. We get something complex. A dead father comes back to life, stepping from a mirror “in three strides.” The brevity of the lines, some of which have three words, echoes the movement of this apparition, and the white space hemming the text to the left might well reflect the supernatural atmosphere.

Thompson is not concerned with giving us A Christmas Carol; rather, he clears the snow to reveal his father’s story, its injustices, its traumatic effects, given the father’s time in military service at the behest of an empire that would later forget members of the colonies had served it. The resurrection is of a history that is just one of many lost stories, as the title of Seni Seneviratne’s recent collection Unknown Soldier, also published by Peepal Tree Press, reminds us. Grief coalesces with a sense of estrangement that forces one Thompson poem to ask, “born in London,/was I English”?

But detours along the way, such as The Weight of the Night, a poem in which a couple comes to terms with a rape, suggest the book is more generally concerned with the incursion of the past on the present.

The turns circle back, though. The fourth section of the sonnet sequence An Interview With Comedy Genius Olivier Welsh touches the same chord addressed by Dean Atta’s viral poem about the use of a racial slur. The closing sequence, The Baboon Chronicles, has a Kafkaesque vibe, but this report to the academy submits to the yoke of race and, perhaps, the surreal politics of Brexit.

Grief’s quietude, history’s silence, memory’s reticence, the reticence of the collective conscious to come to terms with the past – it is all placed on this canvas. Landscape paintings tend to have a bad reputation. But Thompson’s bold strokes show how the heavy issues of life irrupt when you’re in the car, at the cinema, or getting ice cream. It is a trip in all senses, taking us to geographies and social realities, that, finally, amounts to a portrait of a pain that knows no boundary.

Comments

"Pierrot, Road Trip explore Caribbean identity"