Richard Georges' poems: Skywards

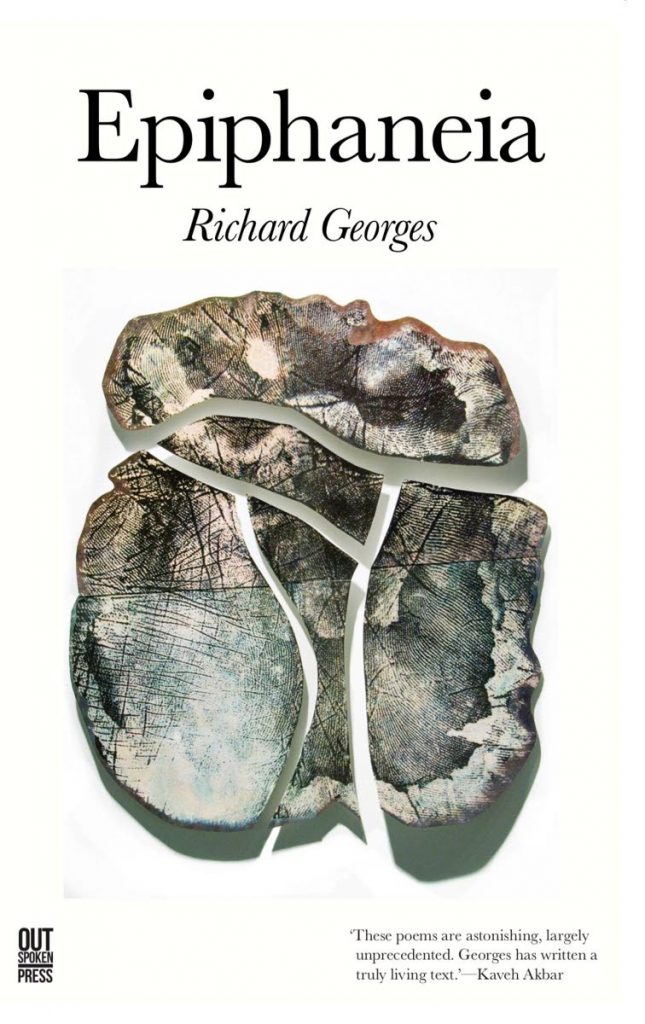

THE CLIMATE crisis looms over Richard Georges’ Epiphaneia, in which the poet takes us to the centre of the storm, the dead calm of a hurricane’s eye – a point from which we can look at all directions in space and time.

The book, Georges’ third, was announced in May as the winner of the OCM Bocas Prize for Caribbean Literature. Earl Lovelace, the chief judge, cited poems, “lit with the brilliant light of the day-after.” Fellow judge Prof Laurence Breiner praised the presence of “uninhibited intellectual vigor and vision” in poems imbued with “the elation of discovery.”

Discovery is the start. The collection’s title is Greek and means an appearance, a shining forth, a spectacular event. It suggests a biblical revelation (it appears four times in the New Testament) that is simultaneously miraculous and menacing. In a recent online interview with the poet Shivanee Ramlochan, Georges alluded to being inspired by the “deep sense of awe” after storms hit the British Virgin Islands, where he currently lives (he was born in Trinidad).

“You look through the window and see the devastation,” Georges said. “It is only when you can come outside and fully appreciate the extent of the devastation then you understand how minuscule we are in universal terms.” This sense of catastrophe meeting contemplation is reflected in the writing.

Readers of Georges’ previous books, 2017’s Make Us Islands and 2018’s Giant, will find familiar hallmarks of the poet: an interest in sequences, an epigrammatic style, the sense of history and time bending.

The stakes are raised dramatically, however, in the latest book and the elements of Georges’ line rise to the occasion. In the poem The Storm is Here and a New World is Awakening, form enacts the storm and the dishevelment it creates. In enjambed lines, objects rip apart. Pulled away “from the rafters” is “the hollow wail of galvanise tearing.”

This type of rupture is often swiftly followed by a coming-to-terms with causes, with reality, as in the poem Origin. The poem ponders why things always “begin and end with ocean?”

These threads find perfect expression in pieces like A Mixtape for Tortola, where a cassette tape from yesteryear “frames two cyclones.” The conceit gives way to harrowing images of “gutted, gaping houses,” themselves “bleeding wounds,” and a wrecked rescue helicopter becomes a “suspended god” – an inversion of epiphaneia’s splendour.

Within the ecology of the book, stunning images and concepts bounce off each other, as though rocked by storm. Something as ordinary as coffee grounds become “wet like earth,” drenched in the downpour; clouds look “like drowned bodies”; the sun sinks “like a hurled stone” in a jet stream; and morning “begins like a fire.” Even after “the astonishment of exhaustion” the sense of heightened perception extends itself to philosophical questions about time, mortality, the nature of hope and history. The poet’s tenancy to deploy the imperative mode is counterbalanced by the sense of the rug being pulled out from under our feet: “home is a nowhere – a memory; a never was.”

Like a piece of debris, one idea in a poem is thrown and taken up in another.

The premise of An Inventory for Survival finds itself a few pages down in Essentials, a kind of litany in which “Your radio is your altar.” Little wonder this piece is followed by one with the title The Transmutation of Grief, where an orphan child “has a mouthful of fireflies.”

All of this is powerful commentary on what is at stake, particularly for island states, in the climate crisis. But equally, the dishevelment also reflects anxieties about pressing problems facing us like rising tides of xenophobia and bigotry, and, now, the malaise of a world brought to a halt by pandemic.

Yet Georges throws us a rope, threading his book with epigraphs that could act as section headers. These include “Arise, shine, for your light has come,” from Isaiah 60:1, as well as a snippet from Longfellow arguing in life, “the grave is not its goal.” It all closes with its most optimistic note, from Georges himself, “Love always shines."

Comments

"Richard Georges’ poems: Skywards"