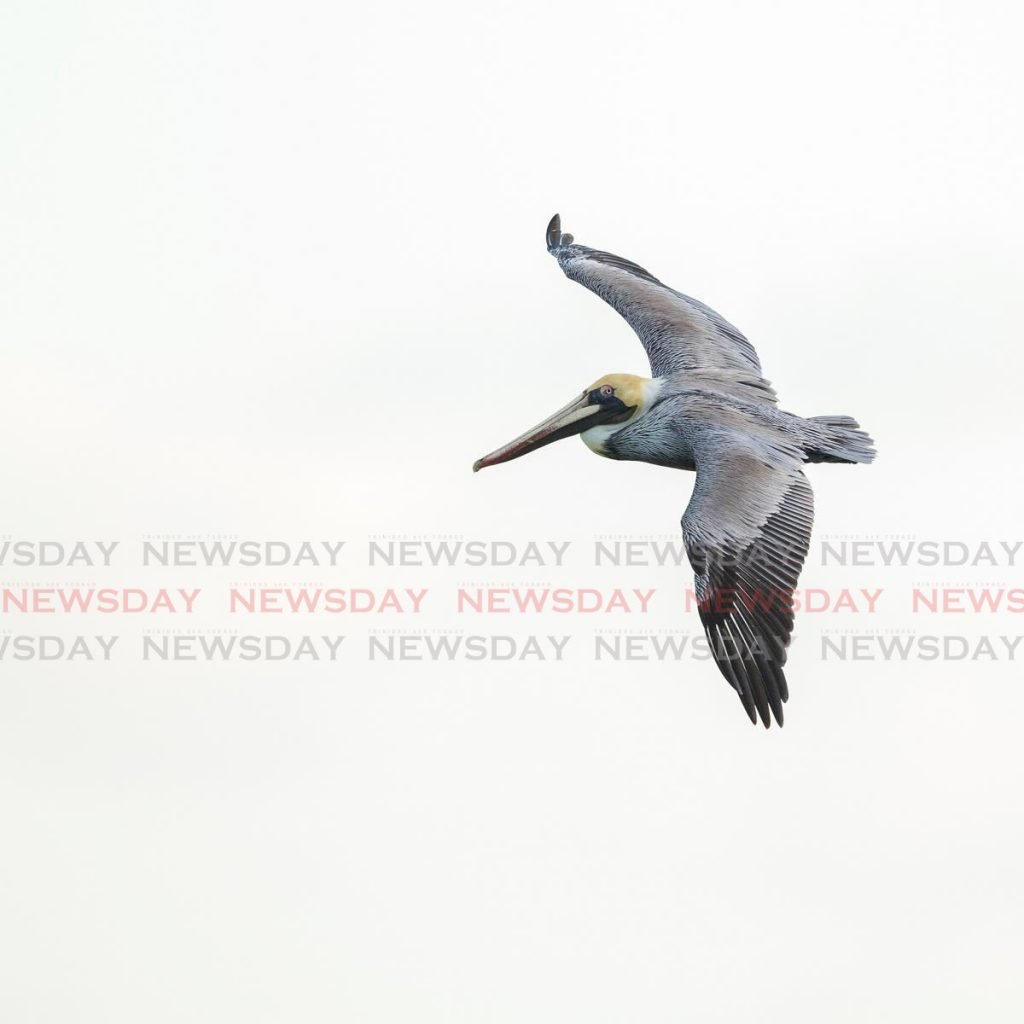

Getting to know Tobago's pelicans

On coastlines around our island, you can see easily pelicans. They nest and breed on the offshore islands that have been designated sanctuaries, and roost on rocks or fishing boats, any perch that offers a vantage point above the waters where fish school. Faraaz Abdool tells us what makes this bird such an efficient fisher.

“A wonderful bird is the pelican,

His bill will hold more than his belican,

He can take in his beak,

Enough food for a week,

But I'm damned if I see how the helican!”

- Dixon Lanier Merritt

Popular in poetry, prose and legends, pelicans have charmed our hearts for centuries. With a lineage extending as far back as 30 million years ago, the eight species of pelicans alive today don’t look much different from their prehistoric ancestors. These large, distinctive birds are distributed across the world, occurring near water on every continent except Antarctica. Their closest relatives are the shoebill and hamerkop – both also incredibly bizarre birds from the African continent.

Among some of the largest birds on the planet, pelicans’ wingspans can rival that of the largest albatrosses; the Australian pelican has a wingspan that can exceed 11 feet! It is therefore no surprise that even though the single species seen here in TT is the smallest pelican in the world, it is still a giant presence on our beaches.

The imaginatively named brown pelican starts its life off as a bald, awkward little creature that looks more like a poorly sculpted baby dinosaur than a soon-to-be seafaring daredevil. Eventually, white downy feathers cover the rapidly growing nestling, and within a few weeks these feathers are gradually replaced by water-resistant brown feathers. Brown pelicans are consummate piscivores, meaning that they subsist entirely on a diet of fish. Young birds are fed freshly caught – albeit regurgitated – fish.

Brown pelicans are social birds, roosting and nesting communally in a particular tree or copse of trees, known as a rookery. Within both Trinidad and Tobago, they seem to prefer mangroves along the coastline, where there is easy access to rich hunting grounds to feed many hungry pouched bills. Often, these rookeries are visible from some distance due to the whitewash on the lower branches. Young birds attain adult size fairly quickly; usually in just over a month. They are however wholly dependent on regurgitated food from their parents for up to ten months. It may seem like they are taking advantage of their parents’ good nature by still begging for food even though they can fly within three months of hatching, but their specialised fishing technique is extremely dangerous, and if juvenile birds do not spend this time honing their craft they are likely to die of starvation or end up mortally injured before they reach adulthood at three to five years of age.

Only two species of pelicans practise plunge diving – our brown pelican and the closely related Peruvian pelican. In fact, the latter was once thought to be a subspecies of the former. Plunge diving involves a few basic steps: locate a shoal of fish that are travelling close to the surface of the water, calculate a desired trajectory and basically fall out of the sky onto the fish, mouth agape. Sounds pretty straightforward, right? Their forward-facing eyes give them excellent binocular vision; large wings enable them to manoeuvre into position with ease. A steep turn to one side is followed by a sharp dive – hitting the water at high speed.

Anyone who has ever performed a belly-flop knows how painful hitting the water can be. So how exactly do brown pelicans escape injury if they’re falling beak-first from sixty feet up? For starters, their bills are designed to cut through water and minimise drag – thus reducing impact forces. Much like an Olympic diver, precisely at the point of impact the pelican’s wings are pressed onto its body, with the wingtips pointed as far back as possible. Also, just before it makes contact with the water, the bird inhales sharply and deeply. Air rushes into special sacs at the base of its neck, as well as within cavities in its bones, buffering against the potentially bone-shattering impact. Once it hits the water, that massive bill opens and its pouch extends, engulfing whatever is in its sight. The open bill coupled with the extra air within its body help slow its descent, ensuring that it pops back up almost immediately after. Brown pelicans do not pursue their prey underwater, even though all four of their toes are webbed – as opposed to only three toes on waterfowl like ducks.

Immediately upon resurfacing, excess water is pumped out of their throat pouch and the fish is swallowed. Contrary to the limerick at the top of this article, pelicans do not store food in their pouch – but this pouch can indeed hold more than its belly can. Brown pelicans possess salt glands that are very efficient at processing seawater; and they have no problem drinking salt water.

While brown pelicans may be a common and familiar sight for us here, it was not always this way. In fact, it was only as recently as 2009 this species was removed from the endangered species list. Widespread use of the pesticide DDT in North America was responsible, Brown pelicans were unfortunate indirect casualties. Fortunately, pressure from the public eventually coerced the authorities to ban the use of the dangerous chemical, and gradually the populations of brown pelicans and many other affected species such as peregrine falcons and bald eagles slowly rebounded.

It is a lesson for us all, an illustration of how the people of a country can influence the decision makers and get them to change – and more importantly enforce this change – thus making a positive difference in the destiny of a wild species. These lumbering birds sure have come a long way, but we must still be careful with our actions, as brown pelicans continue to be some of the hardest hit species in oil spills throughout their range. On Trinidad, a 2013 spill is purported to be still claiming casualties.

Comments

"Getting to know Tobago’s pelicans"