The default to cynicism

BitDepth#1226

IN HIS new book, Talking to Strangers, Malcolm Gladwell offers worrying insights into several assumptions that people make in their interactions with others.

At the heart of the book is a dissection of what he describes as the human need to default to truth, or as we might describe it, trust.

In examining this inclination – which he sensibly acknowledges as necessary for the workings of modern civilisation – he offers painful examples of what happens when that trust and our overestimation of our capacity to read others are misplaced.

Gladwell is a continuously interesting journalist, not least because he is willing to reconsider his previous conclusions in the face of new information.

Some of his conclusions in Talking to Strangers challenge, and even debunk, theories about split-second mental analysis explored in his book Blink.

He bookends Talking to Strangers with the tragic story of Sandra Bland, whose experiences with law enforcement led to her suicide in a Texas jail cell and provided one of the flashpoints that stoked the Black Lives Matter movement.

Between his introduction to Bland’s case and his somewhat overwrought conclusions, he explores the stories of paedophile Jerry Sandusky, Cuban double-agent Ana Montes, financial schemer Bernie Madoff and the puzzling incarceration of Amanda Knox.

In each of these stories, the gulf between what people wanted to see and hear and what was actually being said provides a rich field for Gladwell to till vigorously.

Madoff’s patrician old-world charm won him billions in investments for a Ponzi scheme while Knox’s flippant, quirky response to being at the scene of a gruesome murder put her in jail for four years.

Even an ill-advised thread considering the disastrous relationship between Adolf Hitler and Neville Chamberlain doesn’t dilute the book’s central consideration of our capacity for a fatal mismatch in our perceptions, the errors we make when people don’t act the way we think they should or in ways that defy our expectations.

Our media-induced misunderstanding of what we expect faces to tell us is explored through a dissection of the facial transparency of the television show Friends.

But in listening to his consistent worry about the human capacity to “default to truth,” I wondered about the role of journalists and our flagging commitment to an equally necessary default to doubt.

It’s certainly one consequence of a local media landscape that favours youth and inexperience, usually for financial reasons, and fields reporters with sometimes wildly inappropriate expectations of truth from sources and honesty from politicians.

In my own field alone, I see stories and reports clearly seduced by young tech “geniuses” who wear hip-tight pants and fitted jackets and in that glow of magnificent rightness, hard questions about money, business strategy and tangible results never seem to get asked.

There remains, in the face of such widespread stenography, a role for the sour old journalist who has seen too many outright lies and deft untruths in insisting on more aggressive ground rules for newsgathering.

We aren’t guests at the lavish event; we are observers.

Our job is to be a bit rude and insistent in our questioning, to probe at tender spots that are carefully papered over with pretty words and promises and to care, quite ruthlessly, on behalf of an audience that may not fully understand or care what’s at stake.

According to Gladwell, civil society needs the default to truth to function, but journalists must accept and embrace their role as annoyances unwilling to accept the statement as offered; we must be ready to default to cynicism.

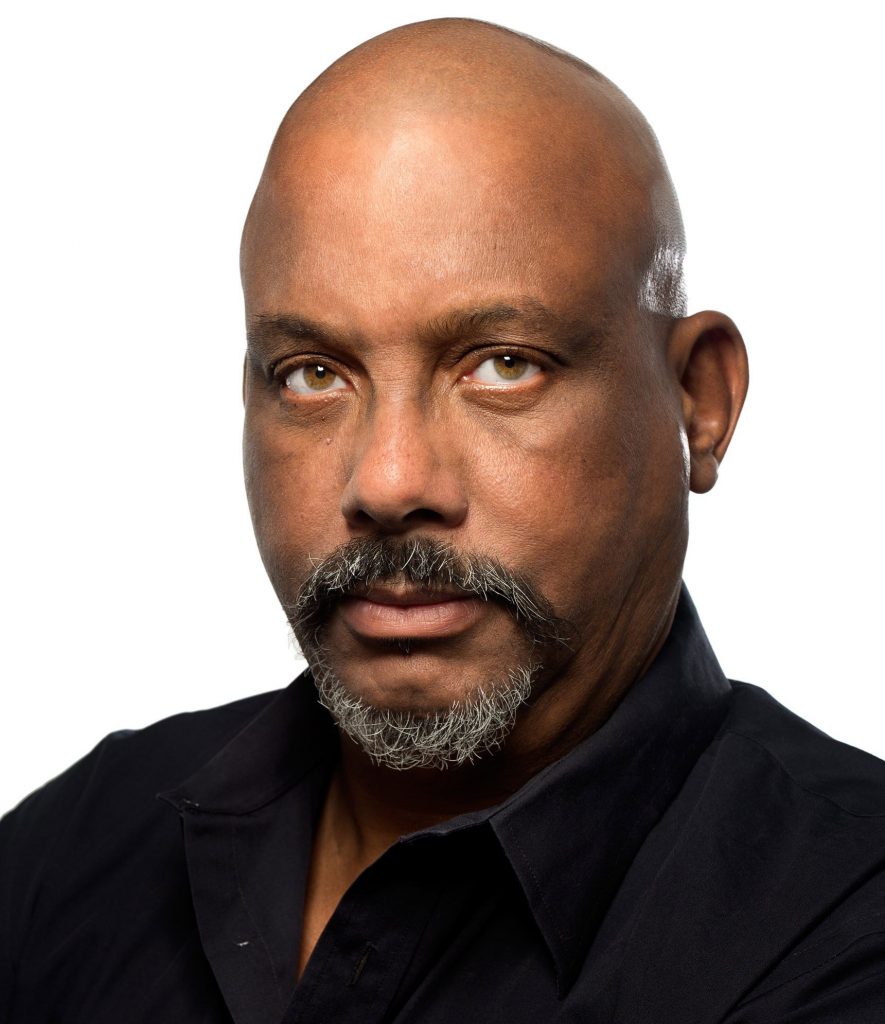

Mark Lyndersay is the editor of technewstt.com. An expanded version of this column can be found there

Comments

"The default to cynicism"