Shannon Alonzo's Sediments takes patrons into the world of mangroves

HASSAN ALI

SHANNON ALONZO’S Sediments invites patrons into a world of mangroves, movement and memory.

Per the zine and pamphlet given to patrons on entry, the show is an exploration of Alonzo’s fascination with Carnival’s capability to create a sense of cultural rooting – of home – for a people.

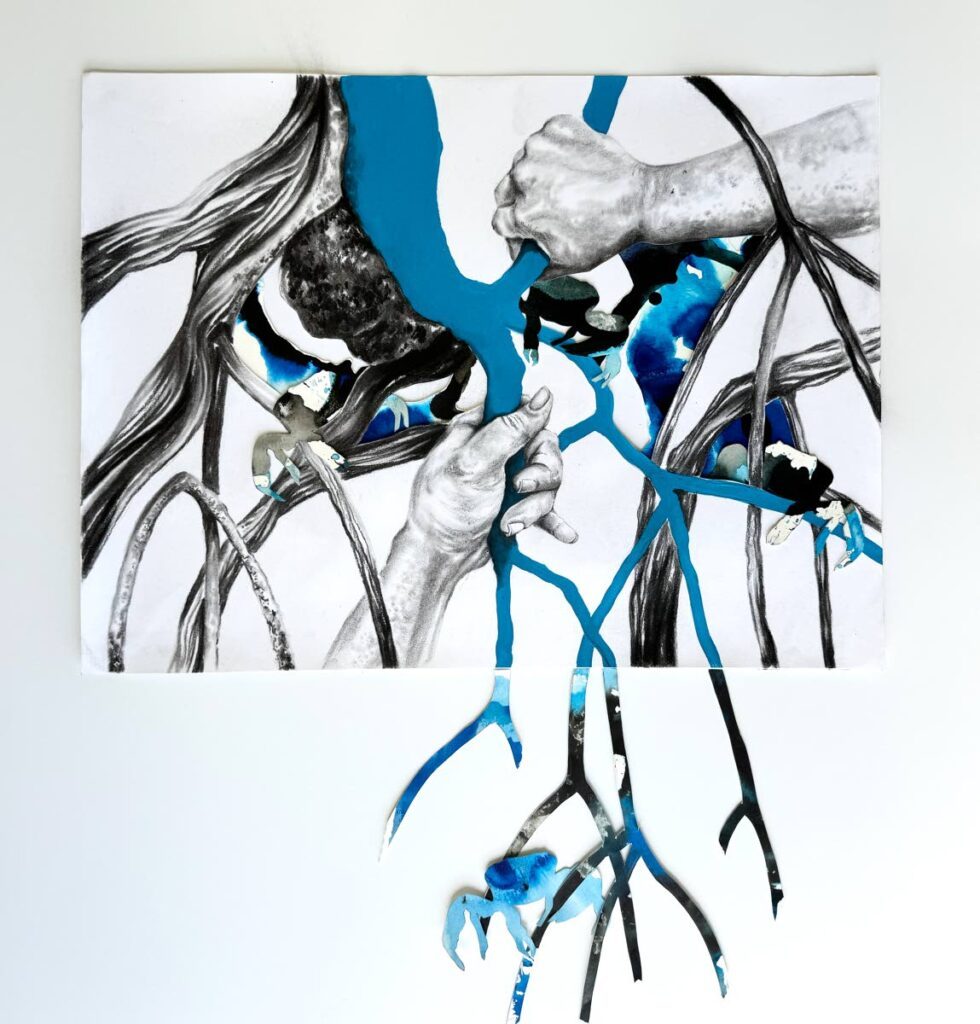

This is made clear by the first piece’s title, Wire Bender. The piece features two layers of paper onto which black and (a singular) blue mangroves sprawl. Scattered along various points of the roots of these mangroves are crabs, coloured in various mixes of blue, black and white.

Two hands are holding onto different root segments of the same mangrove – the blue one – mirroring a wire-bender preparing a frame. This brings the viewer to another of Alonzo’s listed fascinations: the concept of the rhizome.

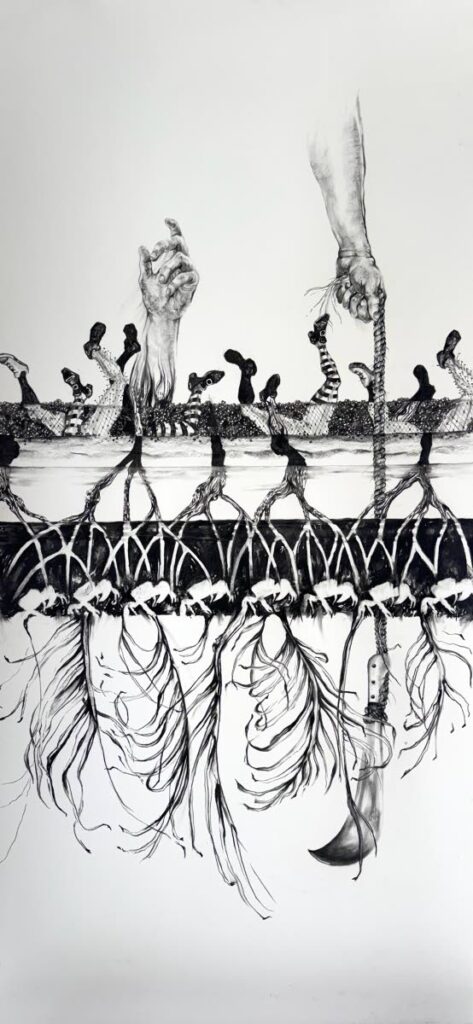

Alonzo is actively referencing Édouard Glissant, a Martiniquan writer, who adapted the concept from the work of French philosophers, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari. Glissant says the rhizome is a means to know the world through relation; through a multicultural lens instead of living in one tradition. While Alonzo acknowledges that mangrove roots aren’t rhizomatic in nature, she says that there is a certain interconnectedness in the appearance of mangrove roots which reminds her of the concept. Arms grasping mangroves can also be found in Arm/y.

Alonzo says that these arms are another historical reference, this time to Jacob Delworth Elder’s Cannes Brûlées published in 1998. The articles features a retelling of an eyewitness account of stickfighters confronting police with their arms interlock: sticks in one hand, flambeaux in the other. The piece features mangrove trunks sinking into the water, shooting off into roots.

The trees, which go from black to blue to white from top to bottom, are being gripped by six pairs of arms. The water in this piece also changes into all the same colours as the mangroves. Colour comes sparsely in Alonzo’s work.

She says that after working in costume design, fashion, and production design for film and television – notably with Peter Minshall, Meiling Inc Ltd – she wanted to focus on lines and textures, reducing her palette to black and white. At some indeterminate and forgotten date, she wanted to add in colour while retaining that focus on lines and textures and chose blue.

Blue carries many meanings for her: it reminds her of water, of migration (wilful or not) and of the sea imagined as history; blue as a protective colour to ward off maljo; of the film she worked on which featured blue devils, Play The Devil. If one considers all these symbolic meanings, Wire Bender becomes more than interplay between a contemporary, almost-industrial scene of someone bending wire for costumes and the natural twisting of the mangrove roots.

Arm/y, in which the hands are all grasping blue segments of the mangrove, can be imagined as representations of TT’s capability to grasp its histories, narratives – to both preserve them and mould them. Another theme the work tackles is “the female body as a site of liberation.” The female figures within Alonzo’s work are almost all in a state of motion, save for a few disembodied faces.

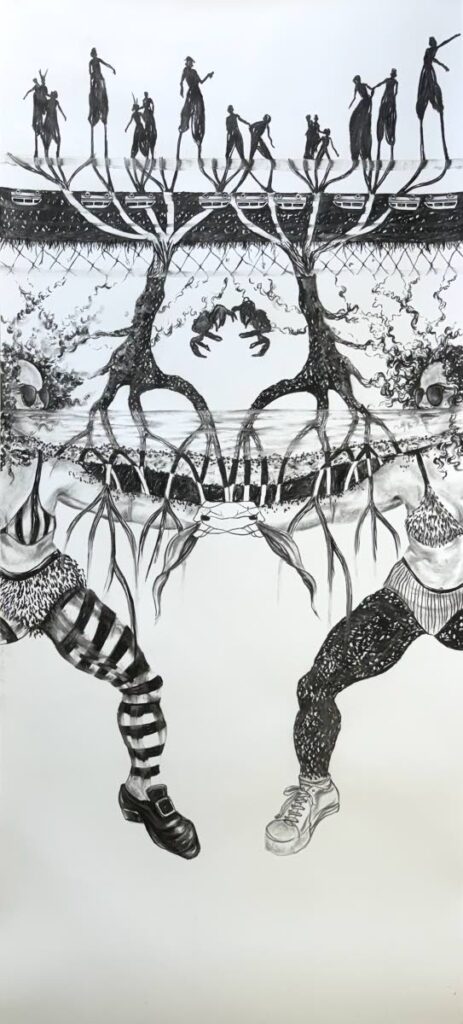

In Chip, three female figures, all caught at different positions in a dance, occupy the top half of the frame. Beneath them, the bottom half of the paper has been cut and painted to show blue, disembodied legs. Blue threads hang from most of these legs – one hangs from the uppermost female figure. She has three pairs of legs sprouting from her head, one striped, one white/blank and one blue. On her hips, a police notice has been placed. The same notice has been pasted over the faces of the other two women. Alonzo says she got these notices as a reference from old police signs prohibiting masks and masqueraders. Furthermore, she notes that identity is one of her concerns with liberation. There is a little irony at play here. The women are free to dance and masquerade as they please, as demonstrated by their motions. If any mask is prohibited here at all, it is the mask of the conscious face.

The striped leg which appears here and in several other pieces comes from Melton Prior’s 1888 illustration of Carnival in Port of Spain for Illustrated London News. It is the first recorded image of Carnival in Trinidad – per Nalis’s website. The identity of the particular character isn’t recorded anywhere – Alonzo posits that it’s either a jamette or a Dame Lorraine. In the mas, women are able to find liberation from TT’s general insistence on “proper ladyhood” and can explore emotions, movements which would typically see them denigrated and degraded.

The largest pop of colour in the room, Occupy My Body, is a massive sculptural work hanging in the gallery’s northwestern corner. It features a large blue banner on which a lavway has been sown with blue and yellow/electric green thread which reads as such: ZINGE TALA LAS ENFAN SANS MAMA MALIWAY. The lavway is repeated twice on the banner. Per JD Elder’s translation in Cannes Brûlées, this means: “Children without a mother see misery in exile.” Behind the banner, soft sculptures of cotton, thread, and wadding take on the shapes of various limbs clumped together. There is also a hat. The fabric here is mostly blue with some madras patterns with colours reminiscent of pierrot grenade costumes. There is again some irony here. Alonzo sees Carnival as being capable of transmuting trauma. In this way, one considers whether TT can be described as “Children without a mother.”

Yes, most of TT’s peoples were torn from a mainland, one way or the other, and in this way can be imagined as motherless children in exile. However, TT has had time to develop its own cultures and create its own expressions. Those exiled children are the grands and great-great grands of today. Through Carnival, specifically its call towards historical remembrance and its appeals to the id (subconscious mind), TT is capable of remembering and celebrating its ancestors who found freedom in exile.

The largest piece of the show, a mural in charcoal on the gallery’s eastern wall, titled Together We Perspire, Together We Retrieve. It features two disembodied faces. The right face has a neck which bleeds into a mess of mangrove roots and murky water below her. From the left face springs a series of legs. Throughout the piece, Alonzo has drawn strings dangling straight down, bearing whistles on their tail ends. The police notice also makes a reappearance throughout the top half of this piece. Alonzo says that she likes to keep her symbols and use them time and time again.

The arms in Arm/y, the twin faces in Perspire and the crabs are all repetitions in her work. This is on-theme for the show. Part of what she wanted to express with sediments is the use and reuse of symbols and tools, the cycles which TT’s culture rolls through – how it seems like Carnival is sleeping until February (or after Christmas you’re a big radio listener).

Sediments runs until March 18. If you’d like to see what memories or murmurs the mangrove has for you, Y Art Gallery, at 26 Taylor Street in Woodbrook, opens from 9 am to 5 pm on weekdays and 9 am to 2 pm on Saturdays. Furthermore, on March 10, Alonzo will be doing a live performance wherein she transforms the contents of the mural. She says that there is no specific plan – only that performances generally go from about an hour or two and that people are free to pass in and leave at their leisure.

About the artist

Shannon Alonzo (born in 1988, St Joseph) is an interdisciplinary artist focusing primarily on drawing, sculpture and performance. She holds a BA from London College of Fashion and MRes Creative Practice from the University of Westminster. In 2024, she was commissioned to present work at Prospect 6 in New Orleans and participated in the exhibition Hard Graft at the Wellcome Collection in London.

In 2023 she was the recipient of an Artist Fellowship from the Caribbean Cultural Institute of the Perez Art Museum Miami and has exhibited work at the Liverpool Biennial 2023, Documenta Fifteen in Germany, Ambika P3 and London Gallery West in the UK, Alice Yard, Loftt Gallery and Black Box in TT and the Atlantic World Art Fair on Artsy.

Comments

"Shannon Alonzo’s Sediments takes patrons into the world of mangroves"