When drawing outdoes the digital approach

MARIAH BISSOON

It is indisputable that we now live in a digital age, when there are handheld devices capable of capturing high-resolution images at our disposal.

With this in mind, it is easy to assume that photographs are the ideal tool for documenting geological data from outcrops.

However, the humble practice of field sketching makes quite a compelling argument against these digital tools.

From a geologist’s point of view, sketching allows one to become more acquainted with the outcrop, hence providing oneself with more intellectual benefits and insights helpful for interpretation that extend far beyond what "a quick photo" can provide. This is not dissimilar to many students' experience that hand-written notes help them remember better than receiving copies of notes.

A fellow geologist, Paul Markwick, once noted geology as a highly visual discipline grounded in primary observations, and I endorse this notion. When geologists sketch outcrops, not only are they engaging in a practice that is cognitive but also deeply reflective.

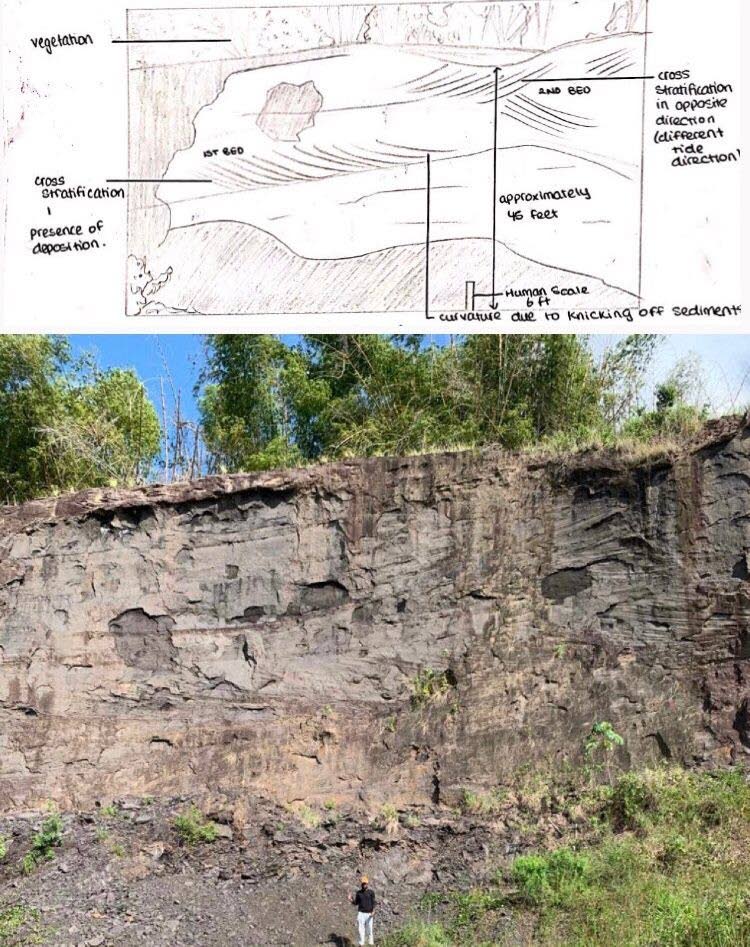

Sketching requires one to be in touch with the subject, creating active observations and recordings which can then enhance and cement a geologist's understanding and allow for the development of more sound interpretations. Moreover, while photographs are a higher-quality depiction of outcrops, they are static, while sketches, on the other hand, are more dynamic. Sketches allow for key details, spatial relationships and overall context of the outcrop to be examined while being drawn. This is because you are prompted to look closer and become absorbed by the outcrop all while actively critiquing your mental model of the structure and composition.

Additionally, as geologists sketch, they often notice patterns and relationships that might be overlooked in a photograph taken with minimal thought. For example, subtle changes in sedimentary layers, textural variations and structural deformations can become more apparent when one is actively drawing them.

This enhanced observation can once again lead to better interpretations of geological processes in relation to the geological history of the area.

It can also be said with a great deal of certainty when someone takes a photograph of an outcrop, they more than likely do not annotate or make note of the features within the outcrop immediately after snapping, but will rather keep moving, towards another location. This creates a greater margin for error, as, for one, the time spent observing the outcrop is significantly lower, and certain features are harder to notice unless you have truly adjusted your "lenses" to the outcrop.

The process of sketching also prompts one to make active decisions on what should be included, highlighted, emphasised and even omitted, allowing one to capture and convey the outcrop in its full glory. Moreover, real-time annotation allows a more flexible approach, especially when dealing with complex outcrops, where the ability not only to replicate but also manipulate the intensity of the features displayed is considered an asset.

On top of the interpretative benefits gained from field sketches, there lies a more practical gain, in developing one's retention span and fine motor skills.

Cognitive psychology studies done over a prolonged interval suggest that active recall mechanisms such as sketching improve information recall more than passive observation or, in this case, photographing. The deeper level of processing visual information by sketching allows for more coherency in one’s understanding and a more robust memory of the geology at the surface.

Though one might joke that what is being observed is at the surface level, the intricate details exhibited do not bring about a depth-less approach, but, rather, encourage deep engagement and documentation, which is invaluable to geologists.

To add to this point, I ask you to try to recall your journey as a geological novice in the field. Almost undoubtedly, next to you was your superior, explaining the geological features with a whiteboard or clipboard for drawing in hand. In educational settings, sketching is dubbed an impressive pedagogical tool, and rightfully so.

Field sketches allow students not only to reproduce features but also to connect the dots between depositional environments, tectonic regimes and other data inferred from examining, as well as linking theoretical depictions to real geology.

On a deeper level, it serves as a mental exercise to deepen the comprehension of the features by also recalling how they are formed and the environment associated with the features witnessed.

Using outcrop sketches as a teaching aid really is an invaluable asset in the field, as these sketches can be tailored to meet the educational needs of students, as not all features are clear-cut and easy to interpret.

It is beyond question that sketching in the field is a cherished practice among geologists.

However, the intention of this article is not to denounce photography but to promote the integration of sketching and photographing outcrops on the field. By combining both methods, one has a more concrete and comprehensive approach to documenting geological features.

Photographs can be used as a high-quality, detailed and accurate representation of an outcrop, whereas a sketch provides one with interpretive insights and a mind more acquainted with the features present. This dual and balanced approach allows one to cement contextual understanding while enhancing the quality and utility of observations made.

For example, photographs allow one to capture the distinct colouring and orientation of beds, while sketches can be used to give a general overview of the geology with context.

As geologists navigate complexities in the field, the lost art of field sketching is a proven asset allowing the general field experience to be improved.

In summary, it is unexpected but true that the ability to sketch outcrops in the field leads to a better understanding of oil and gas plays and prospects, hence increasing the chance of success in the exploration of hydrocarbons. In geologically complex regions like TT, this is a key skill that should be honed and not lost because of improvements in digital technology.

Mariah Bissoon is a final-year student doing an undergraduate degree in petroleum geoscience at UWI, St Augustine. She is a recipient of the Wayne Bertrand Bursary from the Geological Society of TT (GSTT) for the 2023-2024 academic year.

This article was submitted by the GSTT.

Comments

"When drawing outdoes the digital approach"