Birds and the Tobago layover

Faraaz Abdool asks us to look out for the birds using Tobago as a rest stop on their annual migrations.

Animal migration has been billed as one of Earth’s most impressive spectacles. This is not the measured expansion of creatures slowly meandering beyond established boundaries; migration knows no borders whatsoever.

As humans, we demarcated a world with strict imaginary lines. Walls and fences and borders separate populations into nations, states, counties, and towns. Falling into this system helps us to forget that we are one planet, a fact that underpins the existence of countless creatures that depend on movement for survival.

Beyond mere wandering in search of food or habitat, migration is a wholescale rhythmic phenomenon. The dance of the rains over the East African savannas ensures that the thundering hooves of wildebeest and zebra continue to follow the fresh growth of greener grasses, timing their reproductive cycle with the gathering storms.

Annual variations of ocean temperature initiate the seasonal migration of humpback whales. And as our planet traces its wobbly path around the sun, the temperate seasons dictate the mass movement of millions of birds.

For us in the southern Caribbean, the annual influx of birds provides a front-row seat to the saga of migration. Timeless yet time-dependent, birds begin arriving with clockwork precision without a clock. Every year, once the cold fingers of winter begin to creep south, these tiny bodies grow restless, maniacally feeding in order to pack in as many calories as possible. Many of these traverse the Antillean arc toward warmer climes in tropical America and back again with the rhythm of the planet.

The exact timing of a migration is determined by a combination of factors. Generally, food availability or the welfare of their offspring would precede a decision to depart brought on by extreme temperature. Some migratory birds spend the entire northern winter in the tropics; others transit through tropical regions en route to temperate regions in southern South America.

Rest stop Tobago

Migratory birds come in a wide variety of shapes and sizes and have diverse origins. Some species that may never encounter each other in their breeding grounds may find themselves in close quarters when seeking refuge in the tropics.

Relatively near to the equator, Trinidad and Tobago sometimes hosts migrating birds from both north and south simultaneously, birds from different continents spending time together for a few days.

In Tobago, one of the most apparent migratory birds is very small. The metallic-sounding vocalisation of a northern waterthrush – “Chink…chink…chink” – begins to punctuate the soundscape across the island from as early as September. As its name implies, it is most often found near water, mountain streams or leisurely rivers. It can frequently be seen on or near the ground within sight of flowing fresh water. The habit of pumping its tail up and down is one of the northern waterthrush’s most noticeable traits.

Northern waterthrushes are members of the mostly migratory warbler family, Parulidae. Other warblers that call Tobago home for many months of the year include the yellow warbler, prothonotary warbler, blackpoll warbler and American redstart. They occupy a variety of habitats, though the prothonotary warbler is partial to mangrove swamps.

Another bird that spends the northern winter in the mangroves is the yellow-billed cuckoo. Like warblers, it is an insectivore. Its larger size means that it preys on larger prey. While warblers will snack on tiny flies and midges, the yellow-billed cuckoo feeds on large caterpillars, moths, cicadas.

In Trinidad, they depend on the much-maligned Moruga grasshopper for sustenance on their northward journey. Few yellow-billed cuckoos spend the winter in Tobago; seeing one is a privilege.

Mangroves and wetlands are invaluable to migratory birds: most migrants to Tobago are dependent on healthy swamps.

Ducks need additional protection against poachers. Both the diminutive blue-winged teal and the sizable northern pintail migrate from far afield to inland bodies of water. Sometimes ducks will form mixed-species groups that travel together. When you look closely at any group of ducks, you may sometimes notice there is an odd one!

From the Arctic to Bon Accord Lagoon

The migratory family of shorebirds, Scolopacidae, consists of some of the farthest-travelling birds on the planet. Sandpipers, snipes, and godwits are all record-setting members of this family.

The white-rumped sandpiper, for example, sometimes spotted on Tobago’s beaches and tidal mudflats, travels from its breeding grounds in the Canadian Arctic to the southern tip of South America and back each year. This global journey takes place in stages, each stage typically involving non-stop flights of up to 60 hours, covering approximately 4,000 kms at a time.

Odysseys like these are only possible with convenient stopover sites – areas that are rich in food, such as the Bon Accord Lagoon and Kilgwyn Swamp in southwest Tobago. Without areas like these, migratory birds would starve on their journeys and populations would be likely to crumble.

Plovers resemble sandpipers, but tend to have a more upright posture and thicker bill. Many plovers feed on worms and small crustaceans accessible at the surface of a sandy beach or muddy riverbank, while sandpipers and their relatives have much longer, thinner bills that can probe deep into soft substrate for hidden morsels.

Migratory birds feed on specific fauna in their stopover. But the birds themselves are also a valuable nutrient source for predators.

However, to be a world traveller at only a few grams, one must truly master the art of flight. Most migratory birds are off-limits for many more generalist hunters.

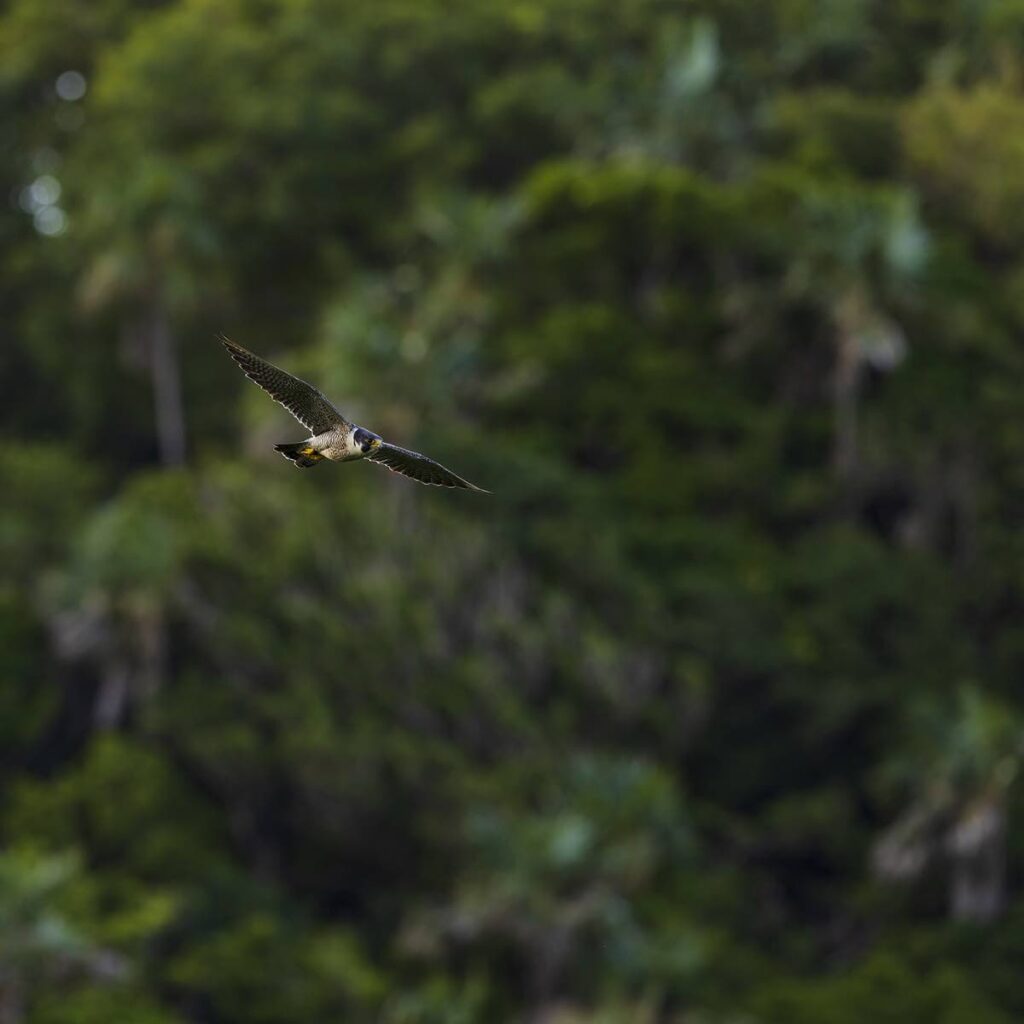

The specialised abilities of falcons, however, make them the perfect predators. But falcons which depend on migratory birds for a food source must be migratory themselves and follow their dinner. The migratory ducks, sandpipers, and cuckoos on Tobago are often terrorised by two species of falcon, the hulking peregrine falcon and the tiny merlin.

The beauty of migration is not simply the movement of birds, but the way it parallels other natural processes. Even the most basic of these involve flow, which underpins migration. This flow transports life-giving nutrients and supports life on all scales.

Whether salmon swimming upstream or oxygenated blood coursing through capillaries, a wider perspective finds the same flow everywhere: the branches of a tree, tributaries gathering into a mighty river, bronchi in our lungs, and, in this case, the paths traversed by migratory birds across our beautiful planet.

Comments

"Birds and the Tobago layover"