Brooklyn Caribbean Literary Festival: Storied bridge between region, diaspora

Founder and executive director of the Brooklyn Caribbean Literary Festival (BCLF) Marsha Massiah is guided by Haitian-American author Ibi Zoboi’s words: “Build the table and they will come.”

This idea was central to the festival’s start. It coexisted with also wanting to share her cultural legacy with her son.

Although not an author herself, the Trinidad and Tobago-born, US based healthcare instructional designer initially saw the festival as an avenue to create opportunities for Caribbean writers in the diaspora and region.

“Because when you live in a diasporic community, the first thing you discover is just how Trinidadian, Jamaican or Grenadian you really are,” she said.

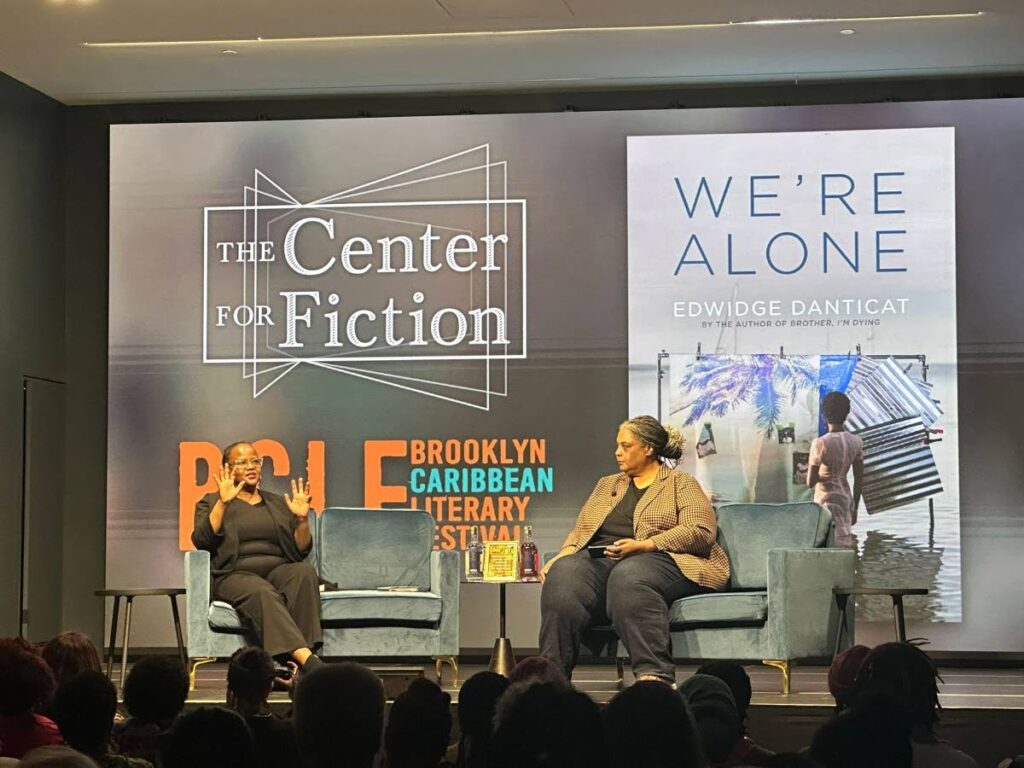

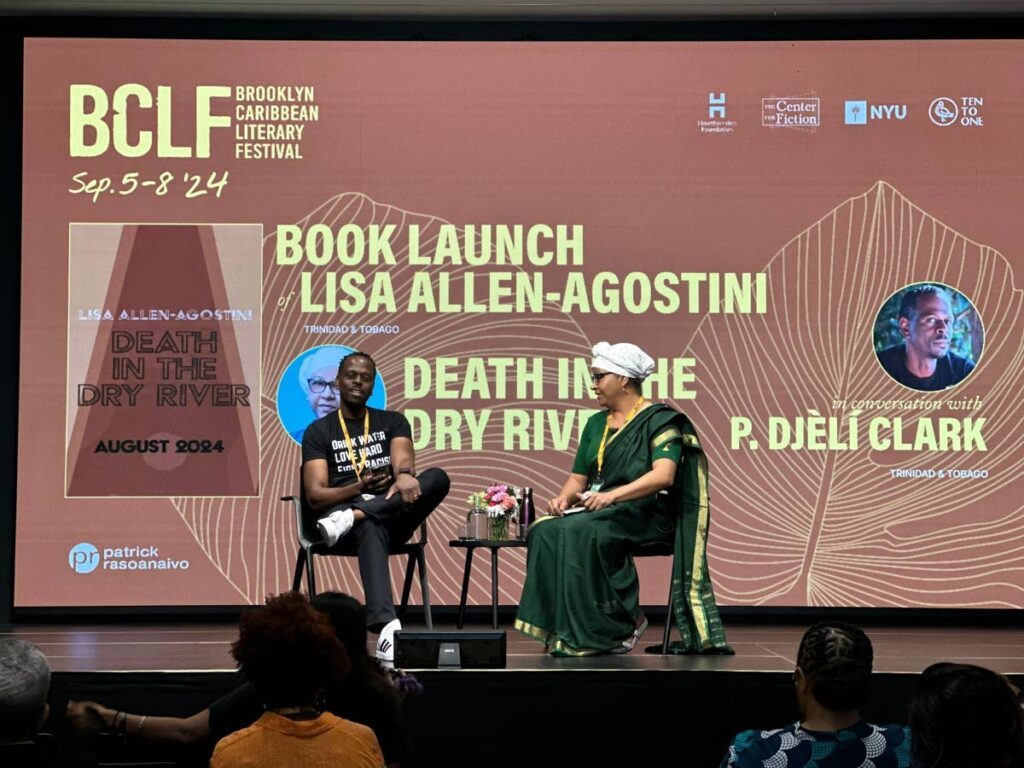

The festival began in 2019. Held annually in September, it has been visited by some of TT’s and the region’s prominent writers such as Edwidge Danticat, UWI vice chancellor Prof Sir Hilary Beckles, Lisa Allen-Agostini and Barbara Jenkins. Danticat’s We’re Alone and Allen-Agostini’s Death in the Dry River were both launched at this year’s festival.

Next year, Massiah hopes to develop an arts-based children’s programme, put together an anthology and launch a new Caribbean voice talent initiative.

She takes pride in knowing that the literary festival is the only one on the US’s east coast that is solely dedicated to sharing the stories of Caribbean people, Caribbean American people and Caribbean diasporic people.

Massiah’s love for literature and the literary arts began with what she described in a phone interview with Newsday as a solid educational foundation at Bishop Anstey High School and the plural nature of TT’s society. Massiah said she had the best of TT’s postcolonial education and that equipped her to perform with a measure of success.

“The festival and the enterprise of the festival was how I thought I would be able to pass on this inheritance and heritage to people in the diaspora.”

She grew up in San Juan and then moved to Trincity. After Bishop Anstey, she read for a double major at UWI, St Augustine, in history and English.

Massiah wanted to build on a conversation started by Danticat about diaspora and identity.

Initially, literature in Brooklyn, New York was very “diaspora-facing” and “meant to lift the chains of Caribbean people who live in the diaspora, meaning North America – USA and Canada.”

But it quickly grew beyond its original vision and became “a bridge for the movement of stories between people in the diaspora and home because we are inextricably linked.”

Although the festival was interrupted by the pandemic, that turned out to be a blessing rather than a curse for the organisers. It gave them a reach they did not ordinarily have, she said. The digital innovations hastened by the pandemic allowed the festival to go beyond limited resources and geographic boundaries. It also gained more attention in diasporic communities beyond North America and grew its appeal in the region.

It gained audiences in Australia and Japan and has continued building on that, Massiah said.

It takes a three-pronged approach: engaging contemporary writers, classic Caribbean writers and netting upcoming ones.

For them, although some publishers might refer to some writers as b-listers, this is not something done by the Brooklyn Caribbean Literary Festival, as each voice and expression is equally valuable, she said.

“As we are hoping to contribute to the development of a robust literary ecosystem, we are giving credence and creating opportunities for everyone to exist at the same time.”

Massiah believes the festival fulfils another important role: allowing people to explore the nuances of their identities.

“When you are here you are not quite one thing; and vice versa when you are at home, they might say you are too American.

“I think the literacy space allows for the fleshing out of identities and just like how we think through those things, providing the opportunity to investigate, interrogate and then come up with the answers collectively.”

A May 2023 Fortune article outlined print was profitable again and its profitability on the rise.

Massiah attributed this to the pandemic, the Black Lives Matter movement and the death of George Floyd. These events led people to question the stranglehold the global minority had on people and how they were represented in literature, publishing, film and art, she said.

Massiah added that the stories of minorities were reduced to almost no existence but the minority was the majority.

“The publishing industry – perhaps in a bit of tokenism during George Floyd – did do some incentives which we benefited from.”

Some black American and Caribbean writers got “really good book deals” as a result, she said.

The festival has also found new ways to market and promote Caribbean literature, like using podcasts, she said. It has two: Cocoa Pod, through which writers voice their work, and BCLF Small Talk, where they speak about Caribbean writing.

It runs a short story contest, which opens on May 1 and signals that the festival will be held in September.

Writing workshops, conversations with authors and book launches are also among the BCLF’s offerings.

Through its work, the organisation has seen more and more publishers contacting it to launch books by Caribbean writers.

“We also see that writers’ bios are now disclosing Caribbean identities – and we are going to take a lot of credit for the relentless work we have been doing in this space to allow writers to own their stories and own their identities and disaggregate themselves from the black American writer,” she said.

The festival has also taken a welcoming approach to its definition of the Caribbean.

“We do not define who being a Caribbean person is according to the Columbian definition of Caribbean. It is not the archipelago that we know. For us, it is wherever the Caribbean Sea touches. So Colombians, Belizeans, Guatemalans, Mexicans are also welcome in our space.”

While the voice of the diaspora might always have been represented in works by people like Marcus Garvey, Sam Selvon and Kwame Ture, Massiah said the voice of the diaspora was now more urgent and was being more recognised.

“Caribbean people have always been making very seminal contributions to diasporic communities. I think we did not possess the language and there was not enough integration perhaps we did not occur in those spaces.

“Journey, as a practice, has been central to us as Caribbean people. I don’t think it is new. I think we now are equipped with the language and consciousness, and that is why communities are now established and larger than they were 50-60 years ago.”

She said when festivals continue to increase in popularity, get support and people show up to support Caribbean writers, a parallel opportunity is created so that these festivals can morph into an imprint – a subsidiary of a publishing company.

This was important for Caribbean people and writers, as it would determine the creative direction which would benefit the region, Massiah said.

It required action from Caribbean people to support Caribbean writers and not wait on someone else to do it for them, she said.

“We have to buy the books.”

She also called on Caribbean people to write reviews for online books, as that was the way Caribbean books would get pushed up the digital algorithm.

Comments

"Brooklyn Caribbean Literary Festival: Storied bridge between region, diaspora"