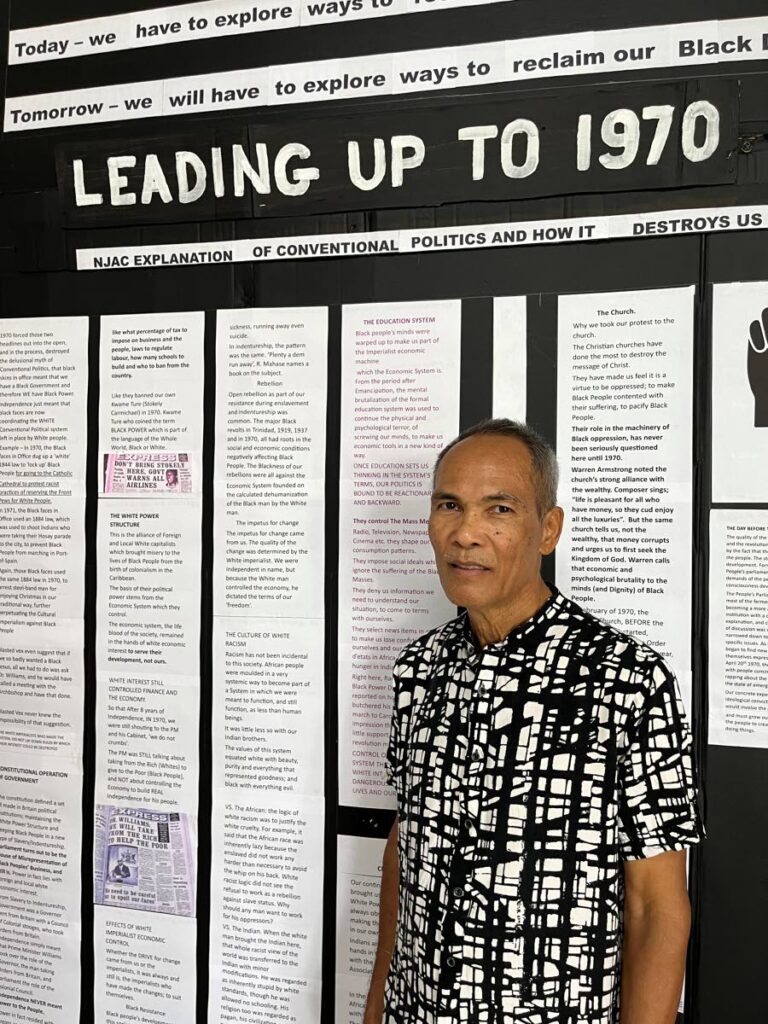

Mario Lewis exhibits Blackness of Our Rebellion 1970

THE Blackness of Our Rebellion 1970, an exhibition by Mario Lewis, seeks to tell the backstory of the February Revolution.

“The exhibition was conceived by Chi Kamose as a text exhibition to be interspersed with archival newspaper reports and headlines of the events leading to the revolution," Lewis said via e-mail after phone interview.

Kamose, 69, is a member of the Emancipation Support Committee (ESC); he joined the National Joint Action Committee (NJAC) as a teenager when the movement was new.

“My life interest has been focused on contributions to addressing the misunderstanding and inequalities between the black/white interplay of the world,” the retired civil servant said.

“The idea was to celebrate the 54th anniversary of 1970 and put it in another perspective,” Kamose said.

“We didn’t want to only focus on the demonstrations. I wanted to explore what were the philosophical reasons behind 1970. There was thought about the political system and the economic system. To show how something that happened on Independence Night, August 31, 1962, led to this.”

The late Makandal Daaga, who would later go on to found NJAC and be a leader of the revolution, is at the heart of the story Kamose tells about Independence Night, 1962.

“Daaga had gone to a party and the DJ put on a calypso and those in attendance revolted against the calypso being played. ‘Take off that calypso, it’s not Carnival!’ We couldn’t rely on our music to take us through. We didn’t have a sense of self. And that was Independence Night.”

The experience led Daaga to found an organisation called Pegasus, Kamose said, “to help people find true and meaningful independence.”

The subsequent revolutionary actions of 1970 – including anti-imperialist demonstrations in the capital, cross-country solidarity marches and vandalism of the RC Cathedral in protest of racist practices in the Church – hinged on this search for the authentic black Trinidadian and Tobagonian self.

“Some changes were made in big leaps, and there have been reversals. But when you come to the exhibition you will see what those changes are,” Kamose said.

“I’ve known Chi for many years through ESC,” Lewis, 55, recalled. As a youth, Lewis joined other makers, including Chi’s son Tau DuFour, in creating some of the iconic public art pieces that marked the ESC’s Emancipation Day celebrations.

“A lot we were exposed to was building our awareness and black consciousness, our enlightenment about history,” Lewis said. He was one of “50 or 60” youths involved in the movement then.

“Some of those young people are now lawyers, doctors, all over the world, doing their own thing. That environment harnessed a confidence that they have carried all their life.” DuFour, for example, is an architect and spatial theorist and teaches at Cambridge.

Lewis’ own path led him to teaching animation, music technology and software engineering at the University of Trinidad and Tobago.

He has continued to make art, and last year showed Forest Notebooks at Medulla Gallery in Woodbrook. The exhibition will be remounted at OXY ARTS in Los Angeles in 2025, he said.

Kamose found Forest Notebooks “an eye opener” about the potential of a similar, unused space Kamose had built in Morvant for his own NGO, Chi Interface.

“He made me understand why he had the space and I started thinking of the possibilities,” Lewis said.

“It could be a studio space for artists; it could also be a space where artists could do workshops, a community space for sharing new experiences, skills and connections.”

Both men live in Morvant, which Lewis said “gets little recognition for what’s good."

"The community that I’m in is rich in understanding what a community should be like; when friends say they’re not coming to Morvant I say, 'Morvant is a big place and it’s diverse in its landscape, population and design.'”

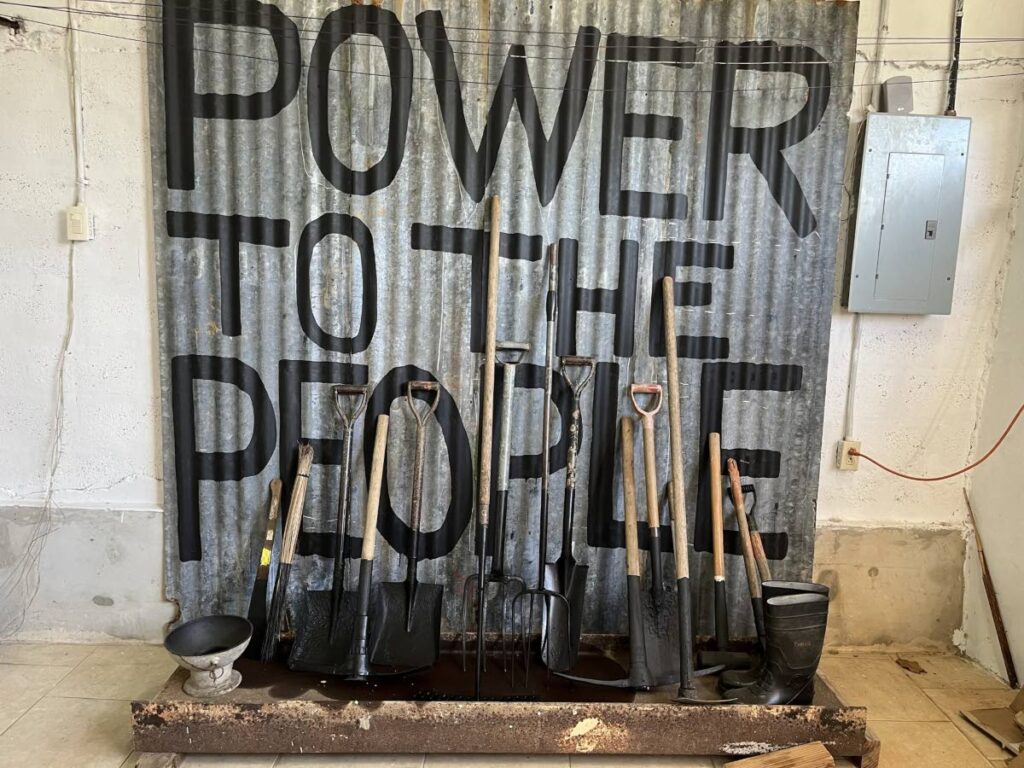

The materials of the exhibition are “cardboard, reclaimed wood, wooden pallets, paper, fabric, used galvanise, found objectives, aquarium and fishes, charcoal, burnt tree trunk, tree branches, emulsion paint, oil paint, photocopies, video projection, soundscape,” Lewis said in the e-mail – a list explained by Kamose in the interview.

“We had no choice of materials,” Kamose said.

“We had to work with what we had. We had old galvanise around the place and Mario put them on the wall. I had no idea what we were going to do with that galvanise.”

The Blackness of Our Rebellion 1970 continues Monday to Saturday, 1 pm - 6 pm, at 4 Flamingo Road, Morvant, until June 1.

Comments

"Mario Lewis exhibits Blackness of Our Rebellion 1970"