On Gadsby-Dolly’s expulsions

The Ministry of Education’s decision, following Cabinet’s approval, to enrol ten “expelled” secondary students in the Military-Led Academic Training Programme (Milat) has raised some important issues.

The disturbing extent of school dropouts, high failure rates and school violence has serious consequences for students as well as present and future public safety.

While we worry about today’s “ten expelled,” it looks as if there are more to come.

Dr Nyan Gadsby-Dolly has several other challenges: two are the 40 per cent not scoring above 50 per cent in this year’s SEA, and over 2,000 school dropouts recorded.

Where have these dropouts gone, from which schools, whose homes?

Three were expelled last year; this year the number grew to ten and counting. These ten have been suspended and repeatedly warned about their troubling misconduct. How effective is her disciplinary matrix?

No doubt the minister has consulted with her National Advisory Committee.

The Education Act (No1 of 1966) states: “The principal of any public school may suspend from attendance any pupil who for gross misconduct may be considered injurious or dangerous to other pupils or whose attendance at school is likely for any serious cause to have detrimental effect upon the other pupils, so, however, that no such suspension shall be for a period exceeding one week.”

Note, among the 11 statutory duties of the school principal are managing ”discipline of the school” and “supervising the physical safety of pupils.”

School supervisors are required to ensure principals conform to the act. So what happened?

Over many years, teachers have been complaining about the classroom difficulties caused by the persistently "gross misconduct” of some students, especially when the expected co-operation from parents was not forthcoming. The restorative treatment required in some schools was also hampered by deficiencies in school management, even though the Education Act provided several provisions for intervention.

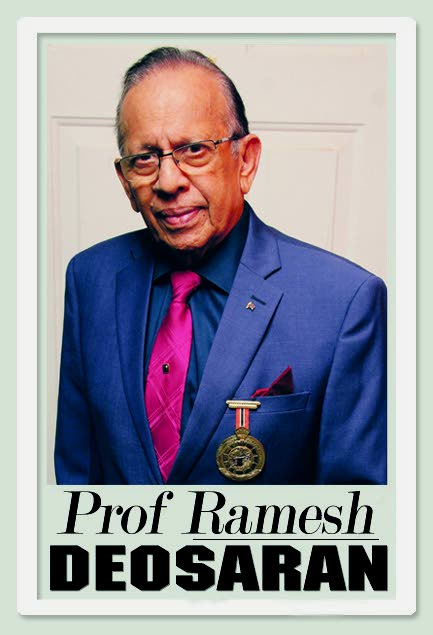

Teachers’ complaints from 20 urban and rural secondary schools about students and their parents were recorded in a research publication titled Voices of the Teachers (R Deosaran, 2008) and submitted to the ministry. We heard of many students rudely “answering back teachers, refusing to come inside the class, fighting, drug abuse, smoking, gambling, illicit sex, extortion, absenteeism, obscenity, standing up in class to insult teachers,” etc.

Some older males (14-16) were “not afraid to tease or threaten female teachers,” all this suggesting how “old” such school problems are.

Accompanying this 2008 research report was a separate, related one titled Empowering Teachers to Reduce Student Violence and Delinquency (Deosaran, 2008). Both reports were presented to each school and the ministry for action.

One complaint from a senior comprehensive school was: “There was recently a major school fight with more than 20 students and rival gangs, like a big riot. School safety officers and security guards were unable to control them.”

There were 30 school-by-school teacher-driven recommendations, ranging in complexity, which were then forwarded in 2008 to the ministry for action.

One was an early “filter and teach” system according to students’ “abilities and attitudes” with matching teachers. Also, an “early proactive disciplinary-control system.”

In fact, in those 2008 reports, we had developed a profile for “high-risk” students for proactive interventions.

Of course, all this takes great effort and resources.

The government changed in 2010.

For this and other reasons, it seems we have an amnesic syndrome affecting some government agencies – forgetfulness, an absence of project evaluation, cumulative progress and continuous improvement. It’s a cycle of one minister inheriting what previous ministers left behind.

The action now taken by Dr Gadbsy-Dolly and supported by both the TT Unified Teachers’ Association and the National Parent Teachers' Association (NPTA) indicates that the time has come to start tackling the problem seriously and sustainably.

The Education Act further states: “Where any pupil has been suspended from attendance the principal of the school shall immediately notify the parent of the pupil and the minister of the suspension and the reasons therefore and the minister may, after receipt of the notification:

"(a) Order the extension of the term of suspension in order to enable proper inquiries to be made

"(b) After due investigation, order the reinstatement of the pupil on a date to be fixed by him.

"(c) Or, order the removal of the pupil to another school including a special school or order the expulsion of the pupil."

There is therefore due process.

However, the uncertainty enters with the “expulsion.”

Now these are students under 16. The minister has no direct control after 16. There is no specific provision in the act as to where to put these “expelled ones,” to save them from themselves.

Mind you, the act allows the minister, if she wishes, to define an institution or build a school as a “public school” for this purpose. Or if necessary, the act itself could be amended to make special provisions for under-16 expelled students.

But something must be done.

Former ministers of education, especially Clive Pantin in 1989, also wanted to “remove” such students. It got controversial. Among the criticisms was the fear of creating “boot camps” for young boys. Pantin backed down.

However, it is now time to take the bull by its horns, but with further consideration, especially for girls.

Dr Gadsby-Dolly said: “We are recognising more and more our young ladies are getting involved in negative behaviours.”

NPTA president Walter Stewart, commending the minister’s action, said the NPTA was "very much aware of the success of the Milat programmes and what it had done for many boys.”

Putting police in some schools is a short-term measure, inviting stigmatisation and leading to a “police schools vs prestige schools” stereotype.

School expulsion, however, remains quite a significant symbol, a strong psychological deterrent to other deviant students and their parents.

But like the education system itself, the research tells us there are limits as to how far you can rehabilitate all students who have committed “gross misconduct considered injurious or dangerous to others.”

Like in counselling or psychiatric treatment, a lot depends on the extent to which the targeted individual is willing to change. After all, these students have been repeatedly warned, with parental notice, then suspended, before expulsion.

Even when you place them at Milat, they can leave after 16. Milat, for 16-20-year-old males, holds some promise. It is designed to build discipline, character, goal-getting, attitudes alongside academic training.

If not sent to Milat, where else? Will they become subject to the Anti-Gang Act rather than being inside Milat, especially after 16?

Comments

"On Gadsby-Dolly’s expulsions"