Lighting up freedom of speech

The seven-page 1920 Sedition Act is a threatening set of laws which should interest citizens, politicians, the media, even calypsonians.

It imposes arguable limits on freedom of speech and publication. There are dark fears over state abuse.

It took a Tobago-related hot controversy sparked by late Satnarayan Maharaj and the Sanatan Dharma Maha Sabha’s (SDMS) Central Broadcasting Services Ltd (CBS, radio and TV Jaagriti ) to bring this intimidating Sedition Act again into public light. As explained later, is the Act (Sections 3, 4, 13) constitutional or not?

On April 9, 2019, Mr Maharaj expressed some provocative views on Jaagriti TV regarding Tobago men, PM Dr Rowley’s expenditure on Tobago, etc. This led to a questionable police search for the recorded tape and Maharaj’s fears that he would be charged for sedition. The Telecommunications Authority of TT (TATT) said Maharaj’s statements could be seen as "divisive and inciteful."

Though Maharaj was not charged, doubts arose over the police warrant, and CBS and Maharaj challenged the constitutionality of Sections 3, 4 and 13 of the Sedition Act. As if to bring light to the darkness, attorney and UNC Opposition Leader Kamla Persad-Bissessar, SC, filed a private motion loudly calling on government “to repeal the Act.” PM Dr Rowley said he may amend but not repeal.

Tobago’s then Progressive Democratic Patriots’ leader Watson Duke called for Maharaj to “apologise or face the hate of Tobagonians.”

Letters to the press flowed. (Maharaj died November 29, 2019). The Sedition Act became subjected to heated political debate. It was therefore left to the courts.

As recorded by the Privy Council, (Appeal No 0099 of 2021), as Jaagriti TV talk-show host, Maharaj said “They lazy, six outa ten of them working for the Tobago House of Assembly, getting money from Port of Spain. They doh want wok and when they get a job, they go half pass nine and ten o’clock they go for tea, breakfast.”

He added: “The rest of them able bodied men they doh wah wok ah tall. Run crab race, run goat race and go on the beach hunting for white meat. Yuh see a white girl dey. They rape she.”

Of course, the Privy Council had recognised Mr Maharaj’s irreverent broadcasting style by saying “He often used his talk show to criticise the Government and to express strong and at times provocative statements on matters of public interest.”

At his press conference two weeks ago, SDMS attorney Ramesh Lawrence Maharaj, said Sat Maharaj had a right to express his views even if others disagreed.

Rather than focus on Sat Maharaj’s views, the higher judiciary focussed on the larger issue – the constitutional status of freedom of expression as against Sections 3 and 4 of the Sedition Act, and the necessary tolerance for robust, even “offending” views against the government – as long as there is no clear intention to incite or overthrow the government by unlawful means.

The Act provides, for example: “A seditious intention is an intention

(1) To bring into hatred or contempt or to excite disaffection against government or the Constitution or the House of Representatives or the Senate or administration of justice.

(2) To raise discontent or disaffection amongst inhabitants of Trinidad and Tobago.

(3) To engender or promote feelings of ill-will or hostility between one or more sections of the community. In this, however, there is allowance for lawful public comment to correct government errors, mistakes or defects. (section 3)

The Sedition Act is an Act, like many others, requiring judicial interpretation from broad statutory definition, High Court Justice Frank Seepersad, resting on the “vagueness, lack of clarity and certainty, unreasonable and arbitrary restrictions on freedom of thought and expression, and overly wide definition of seditious intent,” concluded Sections 3 and 4 not constitutional (January 13, 2020). He argued that, fundamentally, the Sedition Act “infringed” the individual’s rights and freedoms in Section 4 of the Constitution.

However, then Attorney General Faris Al-Rawi, obviously flabbergasted, filed “an urgent appeal.” Indeed, Appeal Court judges (Mark Mohammed, Charmaine Pemberton, Maria Wilson) in March 26, 2021, said yes – Sections 3 and 4 are constitutional having regard to “well-established common-law principles, time, context of issues facing present-day society,” “tall or turgid language may not necessarily be offensive,” can’t hold a person “into account for something he might have said in the heat of the moment,” there must be “a certain level of latitude for freedom of expression.”

The Appeal Court rejected the arguments of “vagueness and lack of clarity” in the Act. They also emphasised the DPP’s approval before initiating prosecution. Notably, too, the judges were careful to indicate their views are not to "undermine" the Act’s "public order and safety objectives but to balance the scope required for freedom of expression."

But the constitutional fight was not over.

On September 13, 2021, the SDMS and CBS got leave to appeal to Privy Council. The Privy Council hearing was richly served by recalling how sedition laws developed and a flurry of references by the appellants (SDMS) to definitions, case precedents and principles from several countries, and most crucial for us – respect for the separation of powers, especially in granting bail and sentencing.

(For Vijay Maharaj, Peter Knox, KC, Robert Strang, Stephan Ramkissoon: for CBS, Ramesh L. Maharaj, SC, Dinesh Rambally, Kiel Taklalsingh, Rhea Khan: for AG, Fyard Hosein, SC, Rishi Dass, SC, Vanessa Gopaul). Brilliant yet quite modest, Mr Hosein executed razor-sharp arguments at Privy Council in winning for the AG.

Given the recurring view that “existing laws” (there “before 1976 Constitution”) are “immutable,” the Privy Council stated: “One of the functions of Section 6 of the Constitution is to give Parliament the power to determine which pre-independence laws should be retained and which should not.” Mr Knox (SDMS) said the sedition law is “so vague and lacking legal certainty” so as not to meet the criterion of “existing law.” The PC disagreed. It said to accept Mr Knox argument would make it possible to challenge many existing laws. (para. 53)

Quite a precedent-setting opinion. The PC also felt that it must be proven that there was a deliberate intention to incite violence and disorder.

Freedom of speech repeatedly received golden mention. While Lord Devlin said "the jury system is the lamp that shows that freedom lives," Lord Steyn stated: “Freedom of speech is the life-blood of democracy…It facilitates the exposure of errors in the governance and administration of the country.”

In the end, the Privy Council concluded with just one short nine-word sentence: “For the above reasons, the Board dismisses this appeal.” That is, Sections 3 and 4 are constitutional.

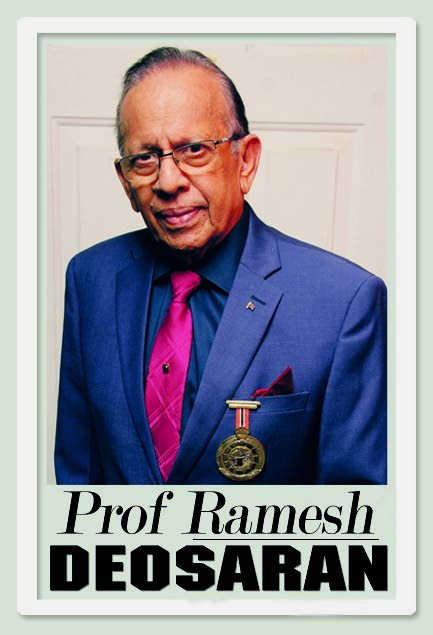

(Prof Deosaran was a member of a Cabinet committee appointed to review the Sedition Act and its banned publications)

Comments

"Lighting up freedom of speech"