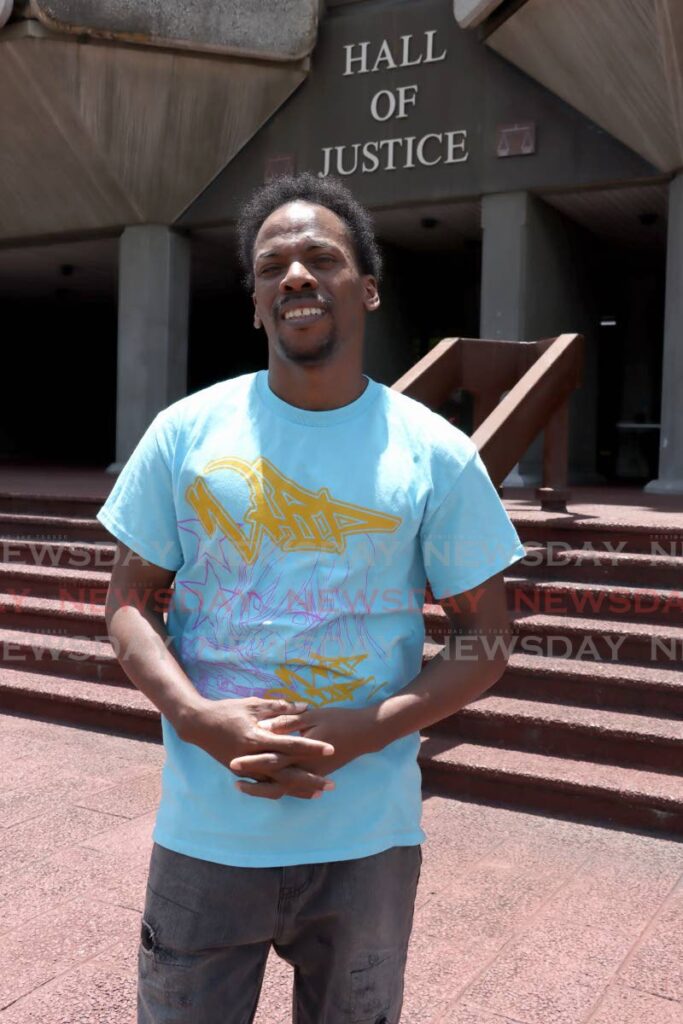

After 14 years in jail for murder, Donnell Inniss's road to freedom

It all felt like a nightmare – except the story Donnell Inniss describes is common for many young men in this country who are charged for murder, tossed into prison and forgotten for over a decade as remanded inmates.

Inniss, 23, from East Port of Spain, was charged for the murder of Ronald Ettienne who was shot to death on September 23, 2009.

Inniss waited nearly 14 years for his day in court.

On April 21, Judge Carla Brown-Antoine found Inniss not guilty of murder in a judge alone trial. It took 11 more days for the DPP’s office to drop some of the gun possession charges against him related to that murder and to untangle the situation with his bail for other gun-related charges.

On May 2, Inniss finally walked out of prison as a free man. He is now 37.

“Before my arrest, life was kind of up and down,” said Inniss.

“I did plumbing in St Augustine, but the work and money wasn’t regular enough. I started to lime with certain friends and sell marijuana for a living.”

Then, Inniss said, he got caught up into things he shouldn’t be doing.

“I was given firearms to keep to protect the community from outsiders. That’s just how it is now. Everyone wants to protect their base. Eventually I started to have guns too. Then my name started to call with the police for different crimes in the area. They’d take me to the station, and give me 72 hours in a cell, but I didn’t do anything wrong so I got out every time.”

But his name kept coming up in police investigations.

“I ended up with a gun and ammunition charge and a shooting case just from someone calling my name. A fellow pointed me out. It’s that easy. When people start to call your name, you can get a charge.”

Inniss got charged with ten counts of shooting, five for shooting at a police officer, and five for shooting at another person.

“In court, I won the five charges for shooting at the man. I still had five counts of shooting with intent against the police officer – even though that person who called my name and got me arrested on both charges never came to court and dropped the charges.”

Inniss spent three months in Port of Spain Prison for those charges and came out in early 2009 on bail.

“I went back to lime with the same group,” he said.

Then, Ettienne got shot and killed in Charford Court, Port of Spain and Inniss’s name got called for that crime.

“The officers came and met us gambling, gave me a gambling charge and carried me down for the murder one time. No one had given a statement, but the street was talking and it said, ‘We think it’s Donnell.’ I knew Ettienne, but we weren’t friends.”

When the police asked where he was at the time of the murder, Inniss said he couldn’t remember.

“It happened about a month before. I couldn’t recall for sure where I was. The police put me on an ID parade and then said I was identified. I couldn’t believe I get this charge, but I still wasn’t worried. I thought, ‘They’ll find out I didn’t do this murder.’”

Inniss remembers he went to prison on a Friday 13. The endless cycle court of postponements began.

“Every time I went to court, I thought it would all be over, but months turned into years.”

After four years, he joined the Wishing for Wings/prison debate team and prison programmes taking CXC English and history classes, PVC furniture making and bible studies. He earned a school leaving certificate.

“I had my common sense, but I wasn’t really educated,” said Inniss.

He had attended Tranquillity Government Primary, Mucurapo Junior Secondary and then Malick Senior Comprehensive before being expelled for fighting in Form 5.

After about five years, Inniss’s case got sent to high court.

By now, Inniss said he felt once the police and the courts had a statement from someone, the case would be sent up the judicial ladder – even if the case didn’t add up.

“No one is bothered by this delay in justice,” said Inniss. “There are a lot of weak cases and once the system gets ten to15 years in prison out of someone, it comes like a win for them. In prison, we talked about how we’re treated like we’re guilty until we can prove our innocence. It’s supposed to be the other way around, but they’re not giving us time to prove our innocence. We’re just locked up.”

Inniss said he was lucky he had family to stand by him. Meanwhile, postponements in the high court turned into nearly eight years.

“The same procedures as magistrate court started all over again: wait until the state is ready. Then the pandemic came and delayed everything a next two years. I kept praying.”

He thought about the purpose of prison, which didn’t seem like a place where justice is served.

“It’s a form of slavery,” he said. “Over 22 hours a day we’re inside cells with four to seven other people. We beg to use the toilet. We have to use newspaper for toilet paper most of the time. No running water in cells.

When a judge was finally appointed to preside over his matter, Inniss said it took about five months for his case to finish.

“I waited almost 14 years for what only needed to take five months.”

The trial showed that the eyewitness' account didn’t match the post mortem.

The state’s witness said he saw Inniss shoot the victim close up. Forensic evidence showed Etienne was shot from a distance.

Inniss returned to prison to wait the dismissal of the gun charges related to that murder.

Inniss did not have the traditional raucous celebration when he left prison. Usually, inmates make noise and shout, “Out there, out there,” whenever an inmate enters the “free world”, but Inniss had asked for the superintendent to summon him to the office so he could leave quietly.

Now, as he reflects on his time in prison, Inniss said he will always remember the experience of being on the prison debate team.

“Learning how to speak in front of people was a very high point for me along with meeting Pastor Gill. He taught me a lot about my God.”

He doesn’t belong to any one religion.

“I would say I follow the Bible,” said Inniss.

He recalls the low points too.

“My grandmother died while I was in prison. I felt helpless. Any time you want to get a picture of hell – that is prison.

He knows life will be a struggle out here.

“People are killing each other. I know a brethren who did nothing and got killed just because they were working on a garbage truck passing through here,” he said.

Inniss would have no faith in the justice if it hadn’t been for his legal team, which included Stephen Wilson, Renee Atwell and Avionne Bruno-Mason of the Public Defenders’ Department.

“People always say, ‘Don’t trust public defenders,’ but my lawyers were the best. They worked as a team and it was an incredible experience for me. Mr Wilson was so fantastic. He stood by my side. I would advise people a lawyer is a lawyer. The private lawyer could be studying money.”

“No effort was spared by the Public Defenders Department in ensuring that Mr Inniss was represented competently and vigorously,” said Inniss’s lawyer Stephen Wilson.

When Inniss stepped out of those prison gates his first act of freedom was to cut his hair.

“Then I went to eat something nice – curry crab and dumpling.”

Ordering food felt so exciting and so overwhelming that Inniss said he tried to eat everything at the same time.

“I didn’t know what to do. I drank some beers. I gave up smoking two years ago so I didn’t do that.”

Inniss will never forget his long struggle for freedom.

Wilson, his lawyer said, “…the evidence spoke for itself. It spoke loudly and caused the judge to return a verdict of not guilty because [the court] was not satisfied that the evidence supported the charges brought by the State against Mr Inniss. It took the criminal justice system 14 years to conclude that a man was not guilty for murder.”

Inniss said, “In prison I used to dream I was out here, and when I came out, I wondered if I was still dreaming.”

The nightmare is over, but there’s no denying that Inniss was robbed of his freedom.

Editor’s Note: See Debbie Jacob’s Monday column on The Donnell Inniss I knew in Port of Spain Prison.

Comments

"After 14 years in jail for murder, Donnell Inniss’s road to freedom"