Changing narratives in Chile, Britain

One of Queen Elizabeth II’s last duties was to ask Liz Truss to form a new government.

Truss was the third female among the Queen’s 15 prime ministers in her 70-year reign, 11 of them Conservative, just four Labour.

A vague chance existed that for the first time an immigrant’s child, a male Tory of East-African Hindu origin, could receive the invitation instead, but the former chancellor of the Exchequer’s resignation precipitating Boris Johnson’s fall was unwelcome, plus his lifestyle was too lavish and his economics too orthodox, and Rishi Sunak lost the leadership of the party to Liz Truss, who stayed put and said what the 170,000 Conservative party members wanted to hear, even though she was not the first choice of many Tory MPs.

There is much to criticise in Liz Truss’s policies, but let’s focus on the revolution she has created by appointing to her 22-person cabinet seven ethnic-minority men and women, three of them to the top jobs of chancellor, foreign secretary and home secretary. Her deputy prime minister is also a woman – the first female duo.

This is very unlike the cabinet of Britain’s first female PM, Margaret Thatcher, who infamously appointed only one female cabinet minister during her 11 years in office. The images of Thatcher surrounded by 22 men, all cut from the same privileged cloth, hardly endeared her to women.

Truss’s cabinet has 30 per cent of women, which is hugely under the 51 per cent they represent in the population, but it is an improvement on all previous Tory administrations, and Truss compensates for it by the rare over-representation of black, Asian and ethnic minorities (BAME) colleagues – 30 per cent – while they constitute only 13.7 per cent of the population.

One Labour-backing British newspaper enjoyed pointing out that 70 per cent of the cabinet was privately educated, while 93 per cent of the public attend state schools, Truss among them.

But like many bright, state-educated people she won a place at Oxford and became destined to meet others who would learn how to inherit the earth. Interestingly, only two of the BAME ministers were state-educated.

People have been asking what that signifies. The answer is that for the Tory Party, which is about enterprise, opportunity, autonomy and getting the job done, class and education matter more than race and religion, even if economic views diverge and different wings of the party exist.

It is striking that the opposition Labour Party has never chosen a female leader or a potential BAME party leader, although it produced the first BAME cabinet members and historically had more women and ethnic minority MPs, including the first black female parliamentarian (of Jamaican parentage).

Just a decade ago it was impossible to imagine a government with the profile of Liz Truss’s.

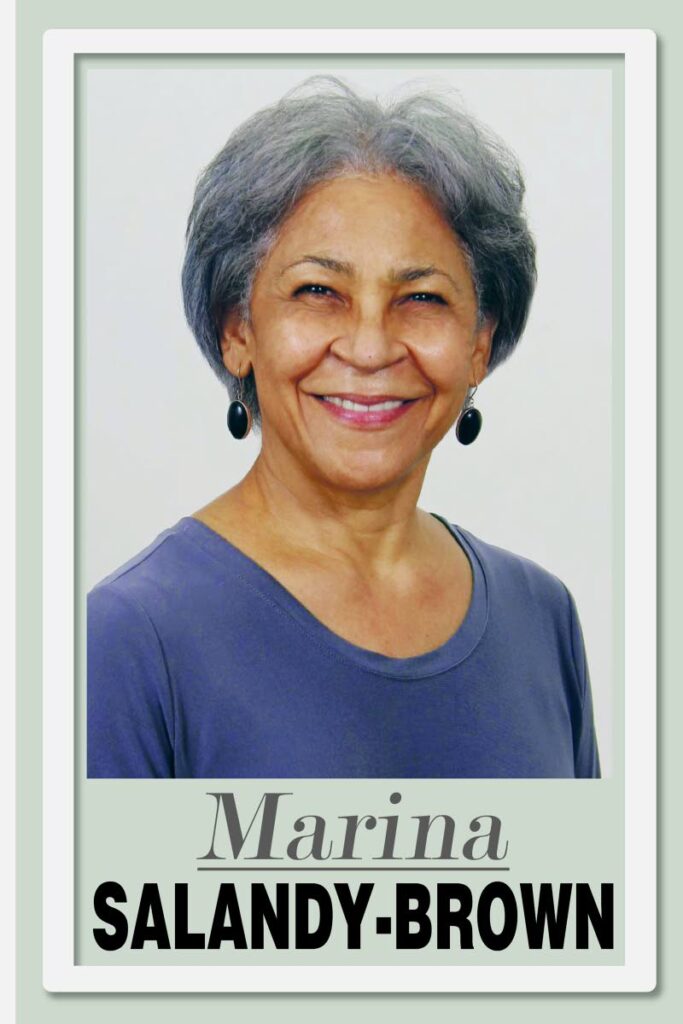

For the women I sat alongside at meetings in the hallowed Council Chamber at BBC Broadcasting House wondering when we might see a female or non-white face in one of the portraits of previous directors general looking down upon proceedings from a lofty height, these political appointments show what we know, that one can dare.

It may seem perverse, though, that the reins get passed at an economic low point that promises recession and worsening crises in energy, foreign affairs, home affairs, health, housing and education.

One pessimistic friend opined that when Truss, her female deputy and her BAMEs fail, they will be hung, drawn and quartered by the media and the reactionary elements of society, and the experiment in diversity will die a natural death, never to be resuscitated, like the idea of being part of Europe.

That might be so, but for some courage, consider recent events in our Latin American neighbour of Chile, where, in a referendum last Sunday, the people voted against the draft of a new constitution. With the rise of something smelling suspiciously like fascism gaining ground in many parts of the world and people willing to bow to unashamed quasi-democratic demigods, events in Chile are satisfying.

The radical left government and its 36-year old president are determined to erase traces of General Pinochet’s stranglehold by rewriting his constitution, which is still in force. The draft was rejected – 62/38 per cent – not because people desire a return to the dark days of military dictatorship, but because they want a workable constitution.

Even supporters of Chile’s new government found the 388 clauses too unwieldy and vague, while others disagreed with the proposed vast extension of social rights and to the personification of the environment. It was simply over inclusive.

Constitutions are notoriously difficult to get right but get it wrong and it comes back to bite you, like it has in TT. Even the US constitution, with its extensive rights, has caused distortions in the functioning of society.

The Chilean people have been very engaged in post-Pinochet social and political change, and seem aware that what is not written in a law is just as important as what is.

They might want to notice the example of Britain, which never codified its constitution, yet its society has remained dynamic and flexible, while its politics has remained stable and shock-resistant, at least so far.

Comments

"Changing narratives in Chile, Britain"