Sterling performances, but pitfalls affect Riddim Nation

NIGEL CAMPBELL

Trinidad and Tobago's Carnival, its ethos, and its traditional characters and creative performances – the moko jumbie, midnight robber, kalenda, the steelband, and more – have been the inspiration for a number of books, plays, dance productions, and even jazz music outside the annual calypso/soca song cycle.

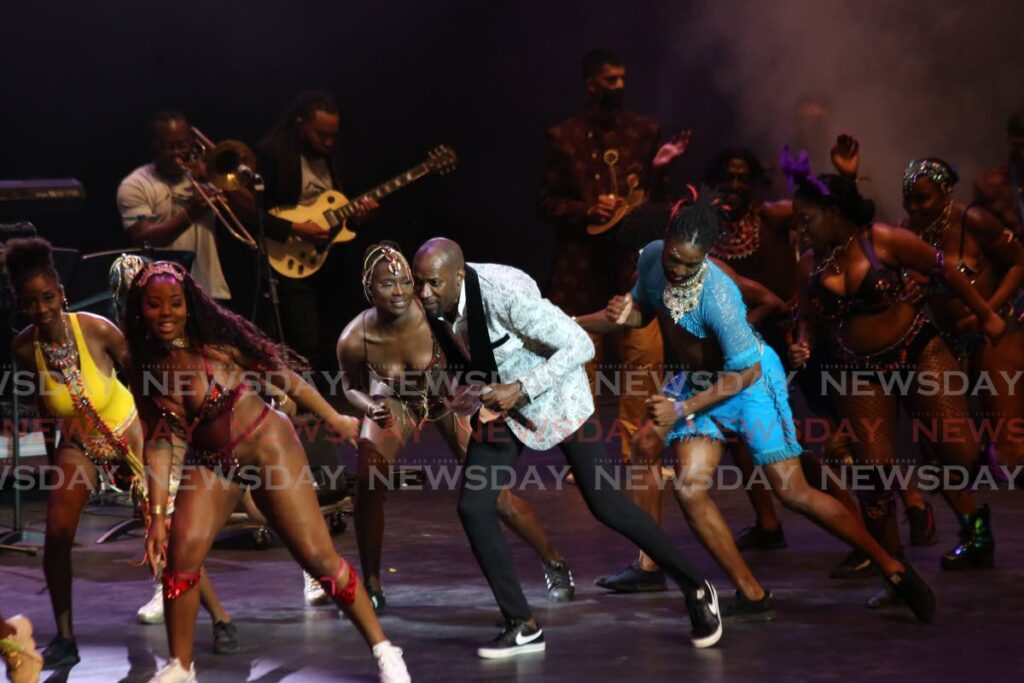

In the realm of local theatrical productions, there exists a significant body of work and a history of pioneering achievements that would justify Errol Hill’s theory of total theatre based on the region’s carnivals as the only true West Indian theatre: “a theatre in which music, song, mime, dance, and speech are fully integrated and exploited.” Add to this corpus of work, the recently-produced Riddim Nation: Bring Yuh Riddim, written and directed by Penny Gomez and produced by Czar Ltd, helmed by Carnival event entrepreneur Jules Sobion.

This production, held on the covid19 limited Carnival Monday and Tuesday at the Lord Kitchener Auditorium of NAPA, Frederick Street, Port of Spain, follows a new trend begun last year by the producer to introduce another element of Carnival entertainment into the milieu devoid of fetes, parades and other mass participatory events. Riddim Nation appears to have been inspired by the Dimanche Gras shows of the 1950s and early 60s, by attempting to pull together elements of our festival heritage under a coherent theme to present a “valid” theatrical production with dramatic dimensions that remains faithful to the spirit of Carnival.

The theme, in this case, is the continuous search and ultimate elucidation for the inherent and sometimes improvised rhythmic pulse that drives the evolution of Carnival music and defines the festival as a whole. Broko, the protagonist in the play, is a young man who is remarkably devoid of rhythm at the beginning of the play. A series of performers and entertainers, within the context of picong, give him short lectures on the origins of the Carnival music development to fill in the blanks, and one assumes, to quantise his rhythmic imperfection.

The evolution of the riddim from African hand drums to tamboo bamboo to iron and pan was noted. The inclusion of chutney music and the celebration of the brass bands were seen as signifying our cosmopolitanism here in TT. As a coda to these stories, the audience is entertained by the performers, in their various musical areas, who give the play a lift where other production elements failed it.

Opening night on February 28 was beset by too many errors to make one believe that this was just nervous jitters. Stage-management woes gave the production a stalled effect that extended the show to close to three hours, but tellingly, exposed an audience to the pattern of the pitfalls and pitiful nadir of bad Best Village drama productions from decades ago.

Scene transitions were hampered by failing projection screens. Sound reinforcement was too poor to lift otherwise sterling performances above a low aesthetic bar. Set design and blocking were uninspired. Dramatic prose was upended by what sounded like Wikipedia entries being recited by untrained actors. A dramaturg, and possibly more preparation before a two-day-only performance would have paid dividends for a local audience.

Some highlights were obvious, as the idea of this kind of production becomes a new normal in a fully-recovered Carnival, and possibly beyond the boundary as an international production. Destra Garcia is a singer and performer of the highest calibre, and her gifts were on full display here. Her comedic timing as an actress playing Broko’s mother Singing Shirley, was admirable. Johann Chuckaree, Nishard M, Drupatee Ramgoonai, and Terri Lyons all shone as performers, signalling that fine stagecraft comes with experience in front of live audiences.

With foreign eyes not widely present for Carnival for the second year, the context of audience participation and involvement was key. This local audience became part of the theatrical experience, and this augurs well for any revision of the play to sustain a unique Caribbean form.

The possibilities from this production and any others to come from Czar Ltd rest with the recognition that the history of Carnival plays is replete with examples of efforts at a theatre rooted in the culture of the country that both have worked and did not work. The legacy of our best writers and dramatists to construct the memorable Carnival theatre experience continues. Errol Hill (Whistling Charlie and the Monster, 1964), Derek Walcott (Batai, 1965, said to be “an unmitigated calamity”), Earl Lovelace (The Dragon Can’t Dance musical, 1986) join many other local playwrights in the battle for positive audience uptake and critical praise for their productions; some won, many lost. Penny Gomez’s name can be added to the roll call of dramatists using the Carnival as a catalyst for a varied entertainment beyond a calypso and a “wine and jam.” We wait to see if it is a temporary addition, or a passing fantasy.

Comments

"Sterling performances, but pitfalls affect Riddim Nation"