The missing mass memory of mas

BitDepth#1344

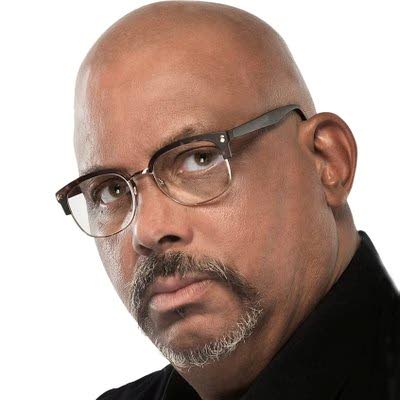

MARK LYNDERSAY

MEMORY IS the basis of civilisation and it is the basis of the reconstruction of our treasured incivility, the celebration of Carnival.

My memories of Carnival span a half-century, beginning with a wonderment at the surreality that characterised the festival just five decades ago.

The trickle of individual eccentricities that sluiced down Hermitage Road in Belmont where we lived with my grandfather over the span of two Carnivals was ground zero.

The violent shuddering of a black jab, commanded by the pistol shot chatter of biscuit tins, obsidian skin glistening in the sharp light of early morning, possessed by a spirit of celebration that urged a portrayal into the realms of the supernatural.

Professional men, fair of complexion but ruddy with the dawning sun who sauntered down the street wearing diapers while sipping from a posey as large as their heads.

But memory is treacherous, depending on multiple vectors of recollection to properly render the past.

Writing and imagery are often our most accessible resources for remembrance, but they are often wrought from singular perspectives without the experience of the senses.

We remember most truly what we have personally experienced, all else is reconstruction.

In distributed cognition, we consider the problem of recall in collaboration, sifting from shared experience and agreed reality.

The accuracy of the result depends a great deal on the quality of the group's collective memory and its willingness to be ruthless in pruning errors.

Studies of collective intelligence applied to problems suggest that group cohesiveness improves results when a cohort of people works together collaboratively toward an identified goal.

By any of these measures, the recording, codification and accessibility of the history of all aspects of Carnival since the first street parades of 1838 have been appalling.

Trinidad's Carnival is in shouting distance of its 200th anniversary. What can we say that we truly know about this festival that is convened with such passion each year?

In 1987, the last issue of Key Caribbean's Trinidad Carnival was published. For at least a decade, the publication, helmed by Roy Boyke and Pat Ganase, stood as a benchmark in recording each year's festival.

Over the last 35 years what replaced it has increasingly been commercial, editorially under-funded Carnival magazines that reached their nadir in slick photo album books of bottoms in the road published by the largest Carnival bands for their players.

At the turn of the century, Rubadiri Victor began an effort to record the skills and memories of what he called the golden age of creators, which he dubbed the Independence Generation, who worked between 1957 and 1980.

At the time, he estimated that most of that talent would have died by 2012 and a youth generation would come of age knowing little or nothing of their work.

"I identified more than 144 traditions in clear and present danger of dying because the information was only in one or two elders’ heads and created templates for their resurrection," Victor wrote in response to questions about the project.

"More than a quarter of those traditions have since disappeared. At every turn, we were resisted by the State."

What happens to cultural memory when it has no common baseline for reference? When what is remembered becomes a kind of hearsay? When tradition becomes fettered by dogma?

There is often talk, and I am guilty of mouthing this as well, of reinventing Carnival.

But how can a thing be reinvented when we have so little idea of what it was and find ourselves trying to reconstruct it from ever smaller fragments of memory, scattered documentation and a romantic fiction of its past?

Mark Lyndersay is the editor of technewstt.com. An expanded version of this column can be found there

Comments

"The missing mass memory of mas"