Sons of Kwame Ture legacy for new generation

The sons of civil rights activist Kwame Ture did not have much time with their father, but they are carrying on his legacy in their own way as Pan-African activists.

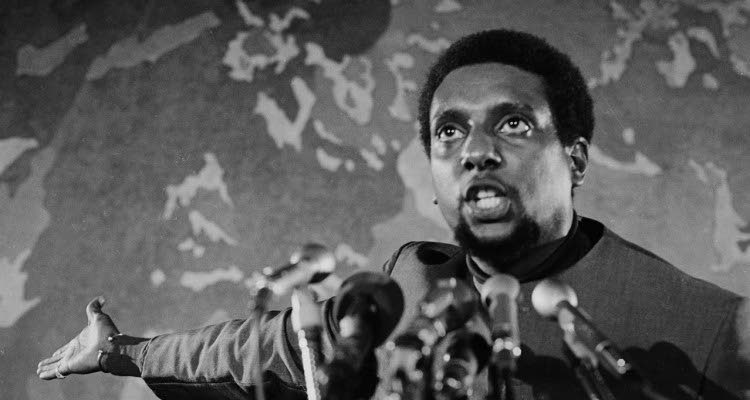

Ture, born in TT as Stokely Carmichael in 1941, moved to the US at age 11 and became involved in black activism while attending Howard University. He was well-known for his part in America’s Civil Rights Movement, the global Pan-African movement, and for popularising the term “Black Power.”

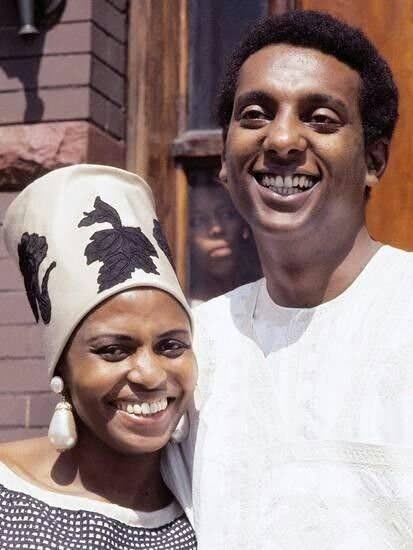

In 1969 he moved to Conakry, Guinea with his first wife, South African singer Miriam Makeba, and changed his name to Kwame Ture in honour of his friends, Pan-African leaders Sekou Touré (president of Guinea) and Kwame Nkrumah (president of Ghana).

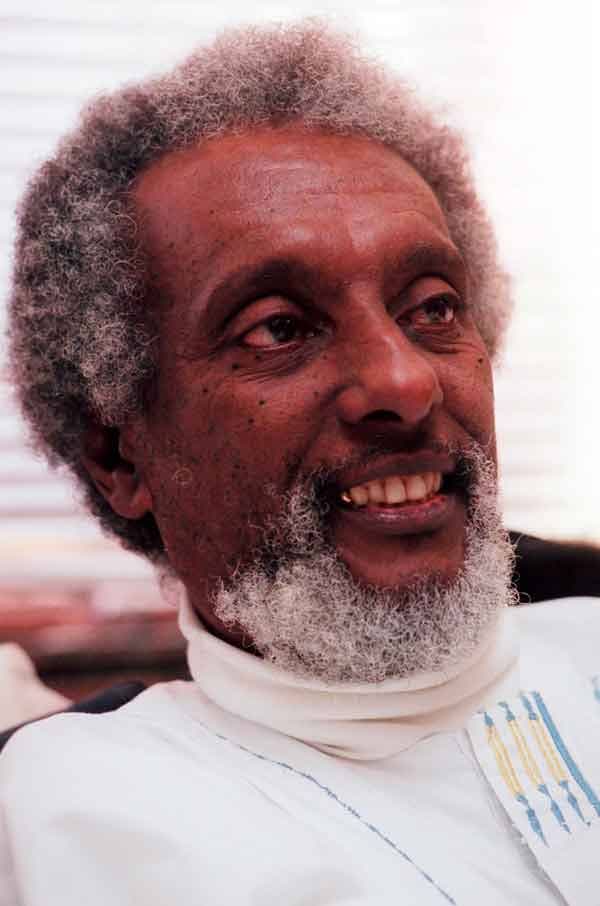

In 1996 Ture was diagnosed with prostate cancer. He was treated at the Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center, New York, before he returned to Guinea, where he died in 1998 at 57.

Sunday Newsday spoke to Ture’s eldest son, Bokar Biro Ture, in Guinea.

At the time he was travelling in a hired car on his way to do some errands before he flew out of the country for work. The internet connection was not great and the call was disrupted several times as people tried to reach him on his phone.

Despite the connectivity issues, he said he knew his father well, as he lived with Ture in Guinea for 11 years before moving to the US with his mother. He also saw his father during Ture’s recruitment tours and travels to the US, and stayed at his home in Guinea during his school vacations.

Bokar, 40, was named after Bokar Biro Barry, a ruler who fought against French colonial rule in Guinea in the late 1800s. He is also a descendant of Barry on his mother’s side.

Ture taught Bokar and his friends maths, politics, history, about people who had an impact on black people both positively and negatively – and took them to the beach to learn to swim.

“I had the privilege of living in the same house with my father for many years. His house was like a community centre. In the neighbourhood where we lived in Guinea it was pretty much like Belmont in Trinidad. It was a tough environment, but his house was open to everyone. All the neighbouring kids used to come there. We used to play there – all my friends would come – and he would teach us.”

Bokar did a degree in economics as well as African American and African Studies at the University of Virginia. He then went to the London School of Economics, where he got his MSc in economic development.

Earlier, after leaving school, he worked as a community organiser in underprivileged communities in the US, then worked at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem, NY.

“A good part of my foundation years were spent with my father whose life was dedicated to the service of others. That obviously had a deep impact on me.

“Then, if there’s one thing I strongly share with my father (it’s) this Pan-African-ness feeling. Anything dealing with the African diaspora is something I’ve always felt strongly about.”

So in 2007, he returned to Guinea, as he always wanted to help develop the continent of Africa. He said he always felt better living in the motherland and outside of “Babylon.”

He told Sunday Newsday while there have been some political improvements for black people since his father’s time, in general economic dependency is an issue around the world. While small pockets of black people are doing well, generally there was a lot of poverty, unemployment, and a lack of certain skills so there is a lot more work to be done.

“The history in Guinea is very colonial, even though it is one of the more revolutionary countries and less colonial than other places. I know another set of history that’s not necessarily available to other people here because a lot of the research is written by other people that are outside of Africa.”

But he said it would be “silly” for him to assume he should do exactly as his father, who was born in a different generation and lived under different circumstances. Instead, he has been working in different fields over the years with the goal of developing Africa’s infrastructure.

However, he says, “I don’t see me working in business or economics as being detached from (my father’s work). I just see it as being my generation’s calling, that we need to have stronger community development.”

He is now an Africa-focused energy and infrastructure project manager with 15 years of professional experience developing Africa and its diaspora. He has managed and helped build national and multinational infrastructure projects in several countries.

“Thanks to the struggle led by previous generations, like that of my father and those prior, we now have greater political freedoms worldwide. Yet we still suffer from material oppression, requiring the building of quality schools, infrastructure, and industries to develop our communities in an inclusive manner. “Developing our limited financial and technical skills, matched with African consciousness, is crucial in making that a reality.

“That is where my greater focus has been as of the last decade and a half, to participate in the socio-economic transformation of Africa and its diaspora.”

He says he would love to put all his energy into political activism, as it remains important, “I nonetheless feel that at this particular juncture in our history, there is a greater need for our global economic development.”

The struggle with racism, he said, can be as direct, as in the US, or indirect, as in Africa and the Caribbean. Either way, western powers or interests still have “their knee on our necks” politically, socially, and economically, he said, in a reference to the killing of George Floyd last year that sparked Black Lives Matter protests worldwide. Therefore, it is important for black people to band together and pay attention to what is happening around the world.

“Say you want to send your child to school in the US for four years, for them to come back to Trinidad. You want to make sure they don’t become a victim because of the colour of their skin. That goes to the Martin Luther King saying, ‘Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.’”

He added that many black people have poor self-determination and need to have greater consciousness and pride in themselves. For example, he said the fact that TT still has street names like Oxford Street (where his father was born: there is a movement to rename the street after him) gives the idea that the country is still looking to Britain and it gives a sense of “psychological domination.”

Brothers in arms

Bokar said he and his brother, Alpha Yaya Ture, are close even though there is a 13-year age gap between them, and the two grew up with their respective mothers.

“I’ve been doing my best to see that he received some political education as my father would have wished. I have also been taking care of his studies, most recently taking him to Tunisia to do a master’s.”

The brothers gave virtual presentations about their father’s legacy at the Kwame Ture Lecture series hosted by the Emancipation Support Committee in observance of Emancipation Day recently.

Alpha, who will turn 27 on August 18, did not get to know his father personally, and only did so through research.

With his native language being French and not being especially fluent in English, Alpha preferred to communicate via e-mail.

He wrote, “Personally I did not live much with my father. When I was born, he went to the USA for two years without coming to Guinea, and upon his return he was diagnosed with prostate cancer. But I recall things where he picked me up from school, or we go shopping before dropping me home.

“His fight influences my life positively, because through his fight I see how many people he continues to illuminate even after his death. He continues to awaken consciousness, and I see him as an idol, not a father proper. That’s why I embarked on the same struggle in another way to defend the voiceless.”

Also through research he learned Ture was a deist: he believed in the existence of a god, but did not care for religion. Relationships with others were important to him.

“I am also a deist and a Muslim, which matters in human relationships. The rest I do not calculate.”

Based in Tunisia, he is an information systems engineer and hopes to graduate with a masters in information systems engineering from the University of Tunis in September.

He is the president of Club Africa Culture at the university, and a member of many Pan-African movements, including the All African People Revolutionary Party of Ghana and Sekoutoureism of Guinea. He is also the communication director of the Convention for Pan-Africanism and Progress in Guinea.

“I evolve as a learner since I have a scientific background. But I am also working on the establishment of an international platform which will be called African Space for Organization. I am working on the bottom for the moment, with the help of certain elders.”

He explained that, like his half-brother, he was named after a Guinean resistance fighter against French colonisation, Alfa Yaya.

He believes a lot has changed for the good since his father’s revolutionary days. He said in the past African Americans did not want to be associated with Africa, but now many have accepted the truth and gone to Africa to visit and even live there. Also, on the continent, young people are becoming interested in the history of Africa and its great men.

Also part of his history is TT, though unlike Bokar, who has been to TT several times for Carnival and to visit family in Belmont and Curepe, Alpha has never visited. He said he is interested in doing so one day, as soon as the opportunity presents itself.

Comments

"Sons of Kwame Ture legacy for new generation"