Finding the local balance for a doughnut economy

An economy based on continuous growth will deplete the natural systems sustaining life. It’s time for a mindset shift to balance and wellbeing, according to Kate Raworth’s proposal for a doughnut economy. Anjani Ganase considers the challenge for Trinidad and Tobago.

Ideas of the growth economy took hold in the last century; there was a global mission to get people out of poverty and improve social wellbeing. For the most part, we have been incredibly successful in improving the quality of lives by getting people out of poverty. In 1981, 42.7 per cent% of the world’s population was in extreme poverty; and in 2018, only 9.3 per cent is still in extreme poverty (World Bank). However, experts have come to realise that endless growth of economies comes at significant ecological cost, especially as many economies are based on extractive industries such as oil and gas, minerals and agriculture. Continuous extractive processes will undermine the very ecological foundations fundamental to our lives. The biggest backlash we face now is climate change, which can thrust a country back into poverty with a single environmental devastation.

It is time to shift from the mindset of endless growth to a new phase of maintaining wellbeing and enhancing social infrastructure and connectivity.

Kate Raworth, an economist and senior associate at Oxford University’s Environmental Change Institute, tells us how in her book Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist. Raworth understands the urgency to upgrade economies of the world to be more reflective of social wellbeing and mindful of ecological limitations. She sees the push for continuous growth as the contributor to many of issues of the 21st century such as ecological disasters and now social disparity because of poor ethics and governance. Raworth has come up with an alternative vision for economies, one that seeks a significant shift in mindset: we stop growing and start thriving.

What does her doughnut represent?

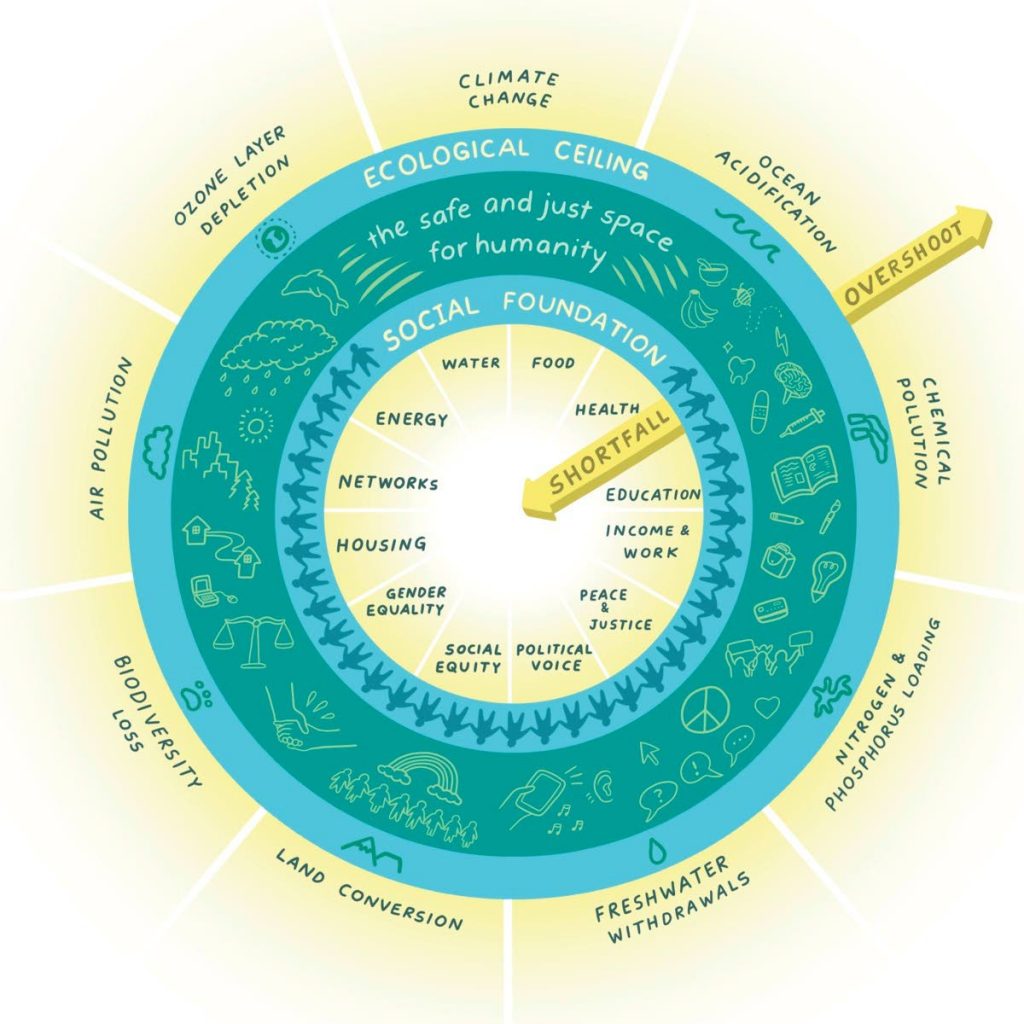

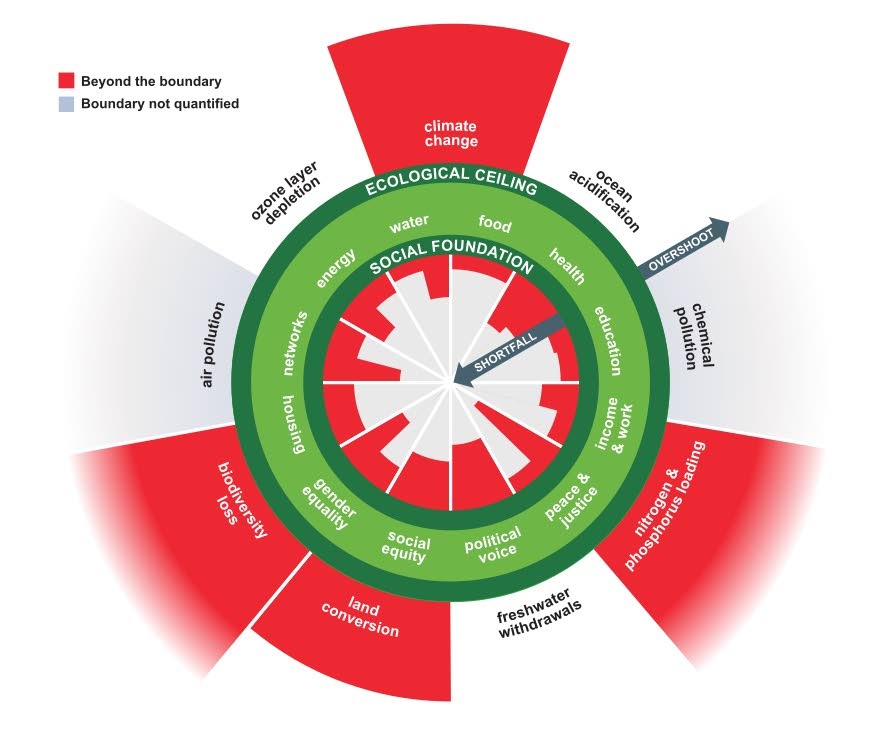

Kate Raworth’s doughnut is a society living in the happy balance where all the social wellbeing needs are met, while avoiding overconsumption and exploitation of the ecological resources that provide life-supporting services. The hole in the centre represents social shortfalls where we must ensure that basic needs, such as education, equity, food and water resources are met. The space around the donut is the zone of ecological overshooting. This area represents things that we have over-consumed and over-exploited which undermine the planetary life support systems. Systems that we have already overshot or are likely to overshoot in the near future include biodiversity, land and ocean resources, the planet’s capacity to mitigate climate change and pollution.

What does the global doughnut economy look like?

Kate Raworth, Johan Rockström and others (2009) paint a clear picture. Today, we see that while billions of people have been brought out of poverty and have had significant improvements in social development, there are still millions of people that suffer social shortfalls, such as lack of a political voice, gender equality and basic health. Meanwhile, we have pushed past the ecological glass ceiling with respect to pollution of our waterways, driven considerable biodiversity loss (68 per cent loss in the last 50 years), land conversion (75 per cent degraded land habitats) and climate change.

For Trinidad and Tobago, our ecological degradation is similar to patterns all over the world. With respect to social wellbeing, Trinidad and Tobago has shown significant improvements in getting people out of poverty, access to education and healthcare over the last 30 years (World Bank). At the same time, we’ve lost over 50 per cent of our coral reefs, lost 12 per cent of our primary forest, lost seagrass beds in the Western peninsula, and lost or degraded the mangrove forests.

If there is continuous extractive growth, then we will suffer further ecological degradation without regeneration and undermine the social framework.

We have also seen the GDP of Trinidad and Tobago’s economy tip downwards over last couple of years; and the pandemic is guaranteed to tip it further with a direct hit to our social development. The solution is not to increase the fund for recovery. Trinidad and Tobago, like the rest of the world, needs to innovate a sustainable vision for wellbeing, balance rather than growth.

How do we meet this vision?

Raworth identifies fundamental insights and methods to assist in the shift towards the doughnut vision; already accepted and applied to cities around the world including Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Under this vision, leaders place wellbeing factors at the centre – health, human rights, labour etc. Methodologies are based, for example, on circular economic principles, where we recycle resources so the waste of one resource feeds another process. Practically, we must consider the waste in all processes, as well as the true and long-term cost of ecological losses. For example, the price of rock from quarries equals loss of natural habitat, loss of biodiversity and clean water, as well as higher flood risks in downstream communities and habitats, and impacts on present and future generations. Multiply this with a factor for increasing drought conditions and warmer temperatures.

In the post pandemic, Trinidad and Tobago would have taken an economic hit that will no doubt compromise the wellbeing of our nation. However, as we move towards economic stability, let us include a plan that allows the society to thrive by decoupling wellbeing from material wealth and extractive systems.

How can TT thrive while maintaining a healthy planet?

We need to visualise a good life in TT along the metrics of the doughnut economy rather than dollars and cents. We need to visualise TT as resilient with a healthy social and ecological biome. All the cards need to be on the table, including social and ecological values. We then seek only the solutions that satisfy the deficient parameters. While we continue to improve lives and livelihoods, we must include the true social and ecological costs of the things we consume. We need to think about the labour laws in the context of social wellbeing. We need to consider land loss, the waste generated from production to purchase, pollution and carbon emissions. Such considerations can make us more mindful consumers and help us understand our connections to ecosystems and communities worldwide.

Let what we consume be healthy, with low carbon emissions, and ethical in waste disposal. If we build, let the building contribute to green energy. Let us create green spaces outfitted and made with a low carbon footprint, support biodiversity and include community members so that no one suffers social shortfalls. If we innovate, let it be inclusive and holistic to include all social and ecological boundaries. Instead of reaching for more, let us eliminate inefficiencies in distribution systems. Instead of thinking as individuals, it’s time to think as a community.

For more information on the doughnut economy and the work being done to implement, visit doughnuteconomics.org.

References:

Rockström, Johan, et al. "A safe operating space for humanity." nature 461.7263 (2009): 472-475.

Raworth, Kate (2017), Doughnut Economics: seven ways to think like a 21st century economist,

Comments

"Finding the local balance for a doughnut economy"