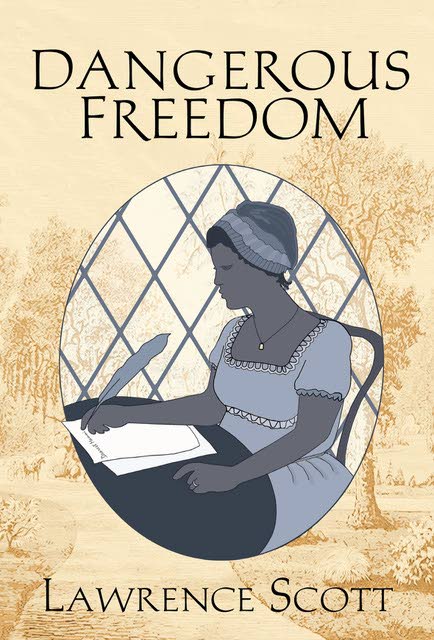

Dangerous Freedom: Lawrence Scott journeys into Elizabeth d’Aviniere's world in age of emancipation

BC Pires

Every age is modern to those who live in it. Two centuries from now, novelists, looking back at events we ourselves find hard to accept as real today, will try to create, in fiction, a real picture of our lives, ravaged as they have been by the lethal covid19 pandemic and the idiotic 45th occupant of the White House.

Future novelists will invent stories around real historical figures to try to convey that, as bizarre as they may seem to people reading 200 years from now, our times were indeed normal and modern for us.

In his new novel Dangerous Freedom, Lawrence Scott’s major achievement has been to put his reader in the mindset of the people of Elizabeth d’Aviniere’s now 200-year-old Age of Emancipation. Baffled readers in 2221 will turn to historically based fiction, made-up stories more credible than their realities, to understand how in hell anyone could have claimed to have loved an obviously self-obsessed ignoramus as Donald Trump.

And Lawrence Scott’s future readers – the novel was published on March 31 – will find themselves in a London (and, to a lesser extent, a Florida) very much like the London in which Elizabeth d’Aviniere lived, a time and place where the law allowed people to be owned like cattle, whipped like mules and jettisoned for convenience, if it meant a profit could be turned.

Elizabeth d’Anviniere died a minor gentlewoman in London but she was born Dido Belle to an African-born slave in Pensacola. Dido may have been her mother’s own child, but she was legally owned by her father.

Scott takes his reader into the world as it then was, where to be black was to be captured on the streets of London and sold to a slave ship headed to Jamaica.

Like her real-life inspiration, Elizabeth “Dido” d’Anviniere lived in fear of her own children being taken from her in this way. And Scott’s reader today knows what it is like to live in d’Anviniere’s constant fear of the loss of freedom itself.

Scott was not the first creative person to notice how well his subject lent herself to fiction. Her modern English biographer, Paula Byrne, was engaged to write The True Story of Dido Belle in 2014 (subtitled The Slave Daughter & the Lord Chief Justice in the Kindle edition) as a tie-in to director Amma Asante’s film version, Belle, released the year before. The 2013 novel Family Likeness by English author Caitlin Davies was also based on the Dido Belle story. There have been other stories and plays and even a musical.

Indeed, as in all the other works, most of the dramatic interest in Scott’s novel comes from d’Anviniere’s real life: her father, Royal Navy captain Sir John Lindsay, was the nephew of the then Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales and, when Lindsay decided to marry properly – to a white English gentlewoman – he left his mulatto daughter with his powerful uncle, like a favoured pet; but not one the new wife could be expected to accept.

By this alone, Dido Belle/Elizabeth d’Anviniere would be tied to Emancipation, because it was her guardian’s legal judgements in a series of high-profile cases that birthed and helped to shape that movement.

In his own treatment of her story, published by the Dominica-based Papillote Press, Scott covers d’Anviniere’s whole life, from a totally imaginary happy passage to England aboard her father’s ship, to her very real early death. Scott handles his task competently throughout. He knows his way around a sentence.

The novel’s strength, though, comes from Scott’s portrayal of a world the modern reader can scarcely believe could ever have existed, where 132 human beings could be tossed overboard on the high seas, and the court case that arose from it was, not a mass-murder charge, but the insurance claim for the “cargo” of the Zong by the owners of the lost property: a Liverpool slave trading firm.

The reader accepts Scott’s world of 200 years ago as easily as he or she may find it hard to accept our own modernity, where the whole world can watch a police officer extinguish the life of a man whose last words were a call for his own mother… and the outcome of the subsequent murder trial could be in real doubt.

Comments

"Dangerous Freedom: Lawrence Scott journeys into Elizabeth d’Aviniere’s world in age of emancipation"