The gathering storm

The Assassination of Maurice Bishop: Part 1

Godfrey Smith

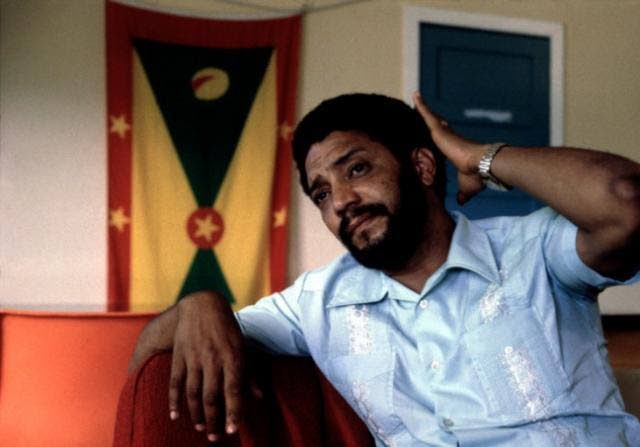

On October 20, 1983 Maurice Bishop, prime minister of Grenada, was shot dead in a bloody coup, along with ten others, after a violent split in his party.

Bishop’s New Jewel Movement had staged the socialist “Revo” in 1979 against the dictatorial prime minister Eric Gairy.

After the coup, US troops invaded the island (TT was one of the few Caribbean countries which opposed the US invasion, along with the Bahamas, Belize and Guyana).

The coupmakers, the “Grenada 17,” were tried and imprisoned. They were freed in 2008.

This week we publish the first of a series of excerpts from Godfrey Smith’s new book The Assassination of Maurice Bishop.

Smith, a former attorney General of Belize, is the author of George Price: A Life Revealed (2011), for which he won the Bocas prize for non-fiction in 2012. He is also the author of Michael Manley: The Biography (2016).

Smith spent 76 days in Grenada doing research and interviews for this book. He takes part in a panel discussion, A Question of Leadership at the NGC Bocas Lit Fest today.

Shortly before 1 pm they began arriving at Mount Wheldale. The cars revved up the steep incline and slowed at the checkpoint before being waved through to the secure compound. The occupants alighted and walked up the broad, railless, concrete staircase leading to the verandah of the prime minister’s residence. The spacious, colonial-style house with jalousies and an expansive red roof nestled near the summit of Mount Wheldale. It commanded a breathtaking view of ancient Fort Rupert and the picturesque town of St George’s horseshoed around a majestic, turquoise, deep-water harbour, dotted with a flotilla of fishing boats bobbing and creaking as the waves rolled in.

They had been summoned to an extraordinary, three-day meeting of the Central Committee of the party. That it was extraordinary and fixed for three days did not portend any major happening. Central Committee meetings routinely droned on for days like a kind of endurance exercise to build revolutionary stamina. A litany of reports from what seemed like a hundred sub-committees was usually tabled and reviewed. What was unusual, and might have injected a frisson of apprehension, was that all members scattered overseas had been instructed to return home for this meeting, regardless of where they were or what they were doing.

George Louison, the minister of agriculture, hurried back from the German Democratic Republic. Lieut-Col Joseph Layne aborted his studies at the Vistrel Military Academy in Russia, where he had been for the past three months, just four weeks shy of completion. He returned via Cuba, overnighting with his good friend, Leon Cornwall, Grenada’s ambassador to Cuba, who was also a member of the Central Committee. They stayed up chatting deep into the night, making their way to Grenada the following day. Neither man would ever return to complete his assignment.

The 13 members of the committee gathered on the sprawling verandah, catching up with each other as they awaited the start of the meeting. Most were packing Makarov pistols. There was nothing unusual about that. This was revolutionary Grenada; militarised Grenada. Many people walked around with guns. Party activists from every parish of the island earnestly made out a case for a “small piece” as security against counter-revolutionaries, or “counters,” as they were called.

The dictator Eric Gairy, a more charming Idi Amin of the Caribbean, had been overthrown, but the new People’s Revolutionary Government (PRG) was wary that he might try to retake the island. In the early weeks following the coup, the numerous reported sightings of “counters” and mercenaries invading by sea turned out to be just phantoms, imagined by a panicky populace, fearful of Gairy’s vengeful return. The whole island was on high alert.

In that early period, Grenadians walked with their heads held high and chests out, proud as hell of their revolution. Their tiny dot of an island was being discussed in capitals of the world’s most powerful countries.

Teenagers excitedly enlisted in the people’s militia, seduced by the appeal of handling guns and defending the glorious revolution. Even from the affluent families in the posh neighbourhoods like L’Anse aux Epines they came, to receive the rough and ready training. “The People are the Militia; the Militia is the People” was emblazoned on large billboards.

Older folk who joined could expect to find themselves being drilled for two hours by teenaged soldiers, transported at the dead of night in a Soviet-made truck, left in a cane field far from the main road and instructed to find themselves back.

That is how it was in the immediate aftermath of the “revo.” People of all ages and classes were mixing and co-operating, happy for an opportunity to participate in the building of a new Grenada. Revolutionary calypso songs intoned, “From backwardness and oppression to liberation and education; now that we free we have to fight illiteracy.”

But four years on, the halcyon days were fading and some disaffection, like bitter weeds, began sprouting in little clusters around the island. It was said that people were becoming disillusioned. Growth of the militia had flatlined. The enthusiasm of party members was flagging. Some were physically collapsing under the heavy demands of the revolution. At the upper echelon of the party the situation was being characterized as a crisis. This extraordinary meeting, scheduled for September 14-16, 1983, was convened specifically to address this situation.

Two of the 15 members of the Central Committee were not present. Ian St Bernard, the commissioner of police, was ill and Gen Hudson Austin, Commander of the People’s Revolutionary Army (PRA), was en route from Pyongyang, where he had represented the PRG at North Korea’s 35th-anniversary celebrations. He had changed his itinerary to find the fastest route home but still would not make it back until the last day of the meeting. There was none among them whose revolutionary credentials could be questioned. Most had risked their lives in planning and executing the brilliant coup that toppled the dictator. Each was committed, heart and soul, to the success of the revolution.

Just about 50 yards across the courtyard from the verandah where they congregated was the home of Deputy Prime Minister Winston Bernard Coard. He, his wife Phyllis and their three young children lived in a house located in the same compound as the prime minister’s. The Coards’ verandah afforded an unrestricted view of those who arrived and departed the prime minister’s residence.

Not long after the triumph of the great March revolution, the prime minister had moved into the Mount Wheldale premises. His deputy had followed, occupying the adjacent house. Judges of the West Indies Associated States Supreme Court, then headquartered in Grenada, had abandoned the residences and relocated to St Lucia after the PRG suspended the constitution.

It was at the urging of the Cuban security advisers that the prime minister had moved from his home at Parade in St Paul’s to Mount Wheldale. The Cubans had been horrified at the vulnerability of his home, which lay completely open and accessible. Such a high security risk to the leader of the country could not be tolerated, they sternly advised. The prime minister would have happily remained among the people in St Paul’s, but he could not afford to be foolish about it, not while Gairy was still actively seeking support to be returned to power. Too much was at stake. At any rate, the lofty and salubrious atmosphere, high on the hill away from the gaze of the masses, was commensurate with their immense responsibilities. It was no exaggeration to say that the survival of the revolution depended on the prime minister and his deputy staying alive, and Mount Wheldale was one of the safest locations in St George’s. It was where all Central Committee (CC) and Political Bureau (PB) meetings were held.

Living close to each other had been convenient for the island’s two most powerful men who collaborated closely and consulted each other around the clock. At least that is how it had been for the first three years of the revolution. For close to a year, relations had been strained, ever since Coard resigned from the Central Committee and the Political Bureau in October 1982. Mistrust ran so deep now that the PM’s trusted security officer, Cletus St Paul, said he erected a barrier of galvanized zinc on top of the fence to obstruct the Coards’ view into the prime minister’s house.

Coard remained in cabinet as deputy prime minister and minister of finance but had relinquished all party positions and removed himself from party work. He would therefore not be attending the meeting next door. Only members of the Committee and the Bureau were aware of his resignation. The party was so secretive that cabinet ministers who were not party members knew nothing of it. Just a handful of people knew about the strained relations.

Copyright 2020 Godfrey Smith. All rights reserved.

The Assassination of Maurice Bishop is published by Ian Randle Publishers,1 (876) 978 0745, info@randlebooks.com. Available online at www.amazon.com, BookFusion.com and in bookstores.

Comments

"The gathering storm"