Colin Robinson: In his own words

Poet, LGBTQIA activist and Sunday Newsday columnist Colin Robinson, 58, announced in his May 10 column that his colon cancer was terminal.

On May 24 Newsday ran an edited version of this interview (Colin Robinson: Doing the work of memory), accompanied by comments on Robinson from writers and editors.

He answered the questions, posed to him by LISA ALLEN-AGOSTINI on May 16, from Maryland, US, where he is being treated.

Here we present a longer version of the interview:

What’s your full name? Date of birth? Place of birth? Parents’ names and professions? Siblings’ names and order of birth? Alma maters (primary, secondary, tertiary, post-graduate)? Fields of study? Places of residence (countries or districts, with approximate dates)?

Colin M Robinson. I’m 58.

I am not so fond of my middle name, though it is my maternal Scottish clan name or something so. My father, five of his seven siblings, and all three of his children have the initials CM. The combinations are fascinating.

My parents are both dead. (May 23) is the fifth anniversary of the death of my mom, Josceline Stewart-Robinson, who retired as the principal of Diego Martin Central Secondary. She also taught at Woodbrook Sec, in the 70s, and at SAGHS (St Augustine Girls’ High School) when I was born.

My father, Carlton M Robinson, who died 17 years ago last Tuesday, was managing director of TTMF (I think the first local in the role) and chair of the Stock Exchange for a bit, I believe.

I grew up with one twin-like big-sister; we’re 18 months apart and resemble.

My father remarried and his lagniappe, Catherine, was born when I was in Sixth Form. A decade later, at 60, my mother decided to parent a newborn, Christopher. No, he didn’t get an M, but he got my mother’s surname as a middle name.

I came home from the hospital to a house on Davies Street, by Auzonville Park in Tunapuna. A couple years later, the family joined my father at university in Leeds.

In 1969, my mother became the first mortgagee of a house in the new phase of the Diamond Vale estate, which remains my home.

My first school was “Miss Richie’s” (Edna Richardson) on Phillips Street by Lapeyrouse Cemetery. I sat Common Entrance from Trinity Junior. I chose St Mary’s College. I…won the languages open scholarship.

In 1980, I went away to Yale University on the government’s scholarship, but never finished a first degree until 1998…Paralysed by being an adult in a culturally challenging space (it was another decade before every black Ivy League undergraduate had immigrant roots; there were four of us across the university then), and facing competition for the first time, I flunked out after one term, but New York University was happy to accept me and the government’s scholarship, and eventually awarded me an anthropology degree.

I lived in New York (in central Brooklyn, and – for three years, on the cusp of the crack epidemic – Washington Heights) for a decade after my student visa expired before I legalised my status.

One year I was named grand marshal of the Brooklyn Pride Parade.

For the past decade I’ve functioned as a dual resident, between a house with my sister near the U of Maryland campus outside Washington DC and the family home in Diamond Vale.

Who are/were your closest friends?

Moving around a lot, HIV, and a nerdy childhood have meant few close friends alive, which has been quite painful.

I remain in touch with one of my primary-schoolmates, the son of my mother’s “HC” teacher, who lives in Edinburgh and visits home periodically. I have a long and important friendship with another Trini writer in Brooklyn, Anton Nimblett, but few other friendships have survived.

In 2011 I joined OkCupid and the one local match I found took me out for ice cream at MovieTowne. Nine years of macajuelling and three-minute French kisses later, I’ve come to adore him and he’s the closest thing to a boyfriend I have. But he’s not.

What did you do professionally for most of your life? Did you enjoy it? How did you end up in that field?

Hmmm. Do I have a “field”? On my immigration and other forms, I say I’m a writer.

I got CAISO to call me its “director of imagination.”

After leaving school, degree unfinished, I went to work for the colleague of my professor at a mental health research institute on a big epidemiological study of homelessness with public policy implications.

After my first HIV death, my ex, I went to work in HIV and really haven’t left. I did public policy work for most of my HIV career.

I’ve been the first person in almost every job I’ve had, often by creating them at nonprofits. Though its work wasn’t only with gay men, most of my HIV career was at Gay Men’s Health Crisis, and as early as 1994, I was moving toward doing LGBTI policy work, which is where I have landed.

But, again, as we review what CAISO, for example, is championing: it’s protections against age discrimination, ending child marriage, creating a management back office for NGOs.

When did you start writing? Have you always written poetry? Did you ever write in other genres?

I wrote bad poems in English classes at school and one at Alliance Française growing up.

In 1984 I started hanging around a queer writers’ group, Blackheart Collective, doing organising work as a volunteer. In 1986, someone I met there started a writing workshop. I was among the many university-educated guys for whom it became a critical social and support group who brought work secreted in sock drawers – and we all went out to dinner after. A lot of us discovered we were writers. The group started a literary magazine and took work in performance into gay bars and other spaces. I became its leader. And, through the workshop, a poet.

I’ve long done policy-related writing and editing, and the fact that I’m CAISO’s director of imagination reflects the fact that I recognise that what may be seen as business and professional writing is indeed creative work.

For a long time people pressed me to write fiction, and I imagined – like I’d seen so many poets in the academy do – that I was going to be able to pull it off. When I entered the UWI fiction MFA in 2009 (you were a reference), I developed confidence that my writing sample had got me in.

But the responses I got from the instructors to what I wanted to fictionalise cut my nature. What I thought was boldness they found inartful. I’ve not returned to fiction.

As one of the few openly gay Caribbean poets, you have become canon with You Have You Father Hard Head. Who were your influences? Have publication and reader response made you feel differently about the poems in the collection? What’s your favourite piece of your own writing?

But ay-ay, look how I reach “canon.”

I consistently feel like the book has been underappreciated, underreviewed, undernoticed.

As I said, I learned to write in a peer workshop of black gay men. I learned that writing community is the most powerful way to write, that we are each others’ influences and editors and nurturers. Editing and critiquing others’ work is a phenomenal way to learn craft.

Audre Lorde is an undeniable influence, but I don’t know that other than the way we are all shaped by Walcott and Naipaul, Brathwaite and Miller, I am particularly influenced. Ah lie. Roger Bonair-Agard and Cheryl Boyce-Taylor, Trinbs on the New York spoken-word circuit at the time, helped shape my language. Roger and his poem Melda’s Song show up in the poem that opens my book; a line from Shivanee Ramlochan two poems later, Alake Pilgrim and James Aboud and the Spoiler two poems later; a line from Cherríe Moraga at the start of Section III. Perhaps by the gorgeousness of a Lovelace sentence, to whom my poem If Language Were Liquid pays tribute.

The most notable responses to the collection have been acknowledgments, particularly by Amílcar Sanatan, of how the work contributes to the imagination of Caribbean masculinity.

I can’t pick a favourite poem; the one I’m proudest of (and the most widely published) is perhaps The Mechanic. Some of the 1987 poems like Epiphany, about f---ing with Vaseline, stand out. Writing is an Arsenal predicts my cancer.

My favourite piece of writing used to be my March 2015 Guardian column, Grief, Hope, Love & Activism. It is now a passage embedded in one of my Newsday columns (August 24, 2017) about how my mother hid her shame from me.

I think the column has more become canon. It is a space where over six years I have been given the opportunity mostly by (Newsday and former Guardian editor-in-chief) Judy Raymond to write as a gay man about current affairs and culture – and myself. I can think of little like it in the local media. I think it’s the writing I’ve done that’s had the most impact and significance.

Is there uncollected work that you wrote after the book, or work that didn’t make the cut at the time but which you still consider worthy of publication? If so, do you have a plan for it?

I don’t have plans for another poetry collection. Indeed, it seems as if I stopped writing new poems after we made the final cut for Hard Head. So much so that I’ve found it hard to get into writing workshops to try to start writing again, because I don’t have new work to submit.

There are a lot of weak poems about desire on the cutting-room floor.

If you had to do it again, would you establish CAISO? What do you consider its most profound achievement? Its greatest disappointment?

You know, the CAISO board discussed this just last night.

If I had to do it again, CAISO would have been founded in 2007, when the people in the room in 2009 gathered at a Rust Street agency to meet Kennty Mitchell – the maxi driver with the gold caps and the rag over his shoulder who had just won a court judgment after he was arrested, stripped and taunted by a corrupt police officer for being gay.

Our most important achievement is that our discursive work has been key to changing how sex and gender diversity in TT are imagined. It’s not the only factor; but I’ve watched the needle move. While we can’t yet claim any clear policy win for ourselves, we certainly did the critical cultural groundwork that made Justice Rampersad’s judgment in the Jones case possible. Meanwhile, the case has set back our key policy objective. The AG says Government will take no action on either the Equal Opportunity or Domestic Violence Acts (to address gaps in the protection of LGBTI people from violence or discrimination) until a final judgment in the Jones case – perhaps two elections from now.

But our recent reflection did acknowledge two things: we’ve done critical work not just at building mainstream support for LGBTI causes, including from institutional players; but at creating a genuinely intersectional social justice movement.

We’ve been pivotal in coalition victories on sexual offender legislation, outlawing child marriage, and have an onging campagin to protect people from age and health-related discrimination. And achieved significant changes to Government’s NPO Act last year.

Secondly, we’ve rallied some key players around an idea that has nothing to do with sex: the creation of a shared mechanism to make management of nonprofits sounder and more affordable.

Looking back at your upbringing, your family and your early education, what would today’s Colin Robinson tell his younger self at 13 and 25? And, considering your time in the US and returning to TT, what would you tell your younger self at 40?

The ages you chose are fascinating.

Thirteen is the age I remember when I woke up one morning and told my mother in tears that I thought I was a homo. I had a name for the thing that inhabited my wet dreams and daytime fantasies.

I turned 25 in New York in 1986, a transformative year for black LGBTI organising when three key groups formed, all of which shaped my life indelibly.

I turned 40 in New York four weeks after 9/11. That was the incident that set in motion my move to re-anchor my life in TT.

I don’t know that I have for advice that any of those three selves would heed. I guess I would counsel that life holds more joys and successes than hurt and failures. That I would gain self-confidence I have now that I could not imagine then.

Where are you now, and what are you doing there?

Do I know?

I’m currently in the care of doctors at the Johns Hopkins Hospital and my sister in Maryland. Between my eight cycles of cancer treatment starting last year, I think I was in TT four times; and Bangkok and South Africa during two other intervals.

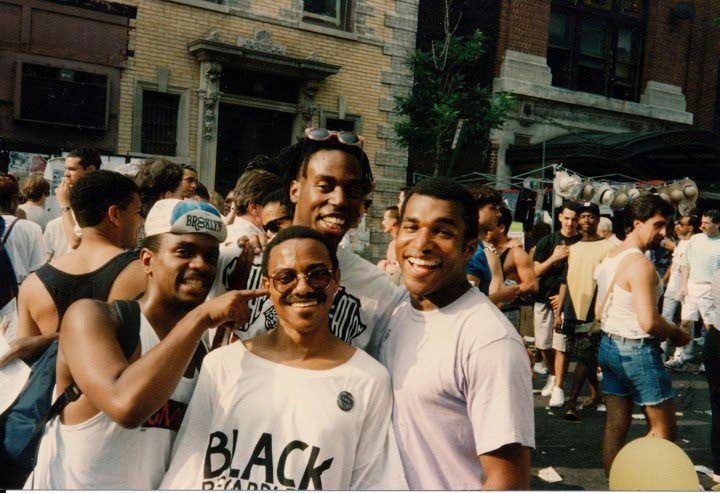

FILE PHOTO

What’s it like to know you’re dying? Is it frightening or comforting?

It isn’t terrifying. I’ve always been comfortable with dying.

It’s really just annoying that I may not get to do a few things I would really like to.

I think I’m probably my best me at the moment.

Is there anything you feel you still have left to do?

What would you say was the thing in your life of which you’re most proud? (Whether it’s something you wrote, a group or action you spearheaded, a relationship you nurtured etc.) Who or what do you imagine you would miss the most (supposing you could miss anything after death)?

I’d like to see two big things happen in TT before I go: 1) the Equal Opportunity Act to be expanded to protect LGBTI folks and others and fulfil Government’s promise four years ago to create a national human rights institution; 2) for the vision of a shared management services hub for NGOs to become real.

And a much smaller one, that a stubborn self-righteous man who pretends he’s the best adherent to international public health guidance, the current minister of health, is standing in the way of: following Caricom-endorsed international public health guidelines and giving HIV-negative people who want it access to antiretroviral drugs to strengthen their ability to protect ourselves from HIV.

I hope politicians won’t cheat me out of all three. But I do plan to haunt Terrence Deyalsingh.

I’ll miss everything. I think I would miss taste and smell most.

I’m proud of my life. Not just one thing. I’m proud that I’ve come to the space that I can say that.

I spent long periods of life unhappy and with a sense of failure and loneliness.

When my mother died just five years ago, I discovered that I had lost a sense of purpose.

I’m proud of the ideas I’ve generated, of the alliances that I’ve built, of the work I’ve written, of the people I’ve been able to share love with.

I’m doing things I never would otherwise, fixing relationships where I’ve held onto stuff, recovering memories and telling stories like never before.

And then I’ll have a moment of panic when going to bed at nights (sometimes in front of the mirror last night, where I see my ageing mother’s face looking back at me) that there will be sickness and pain once again ahead.

But in this stretch of morphine’s relatively stable comfort and enough alertness, I feel blessed.

Comments

"Colin Robinson: In his own words"