Wither calypso

BitDepth#1238

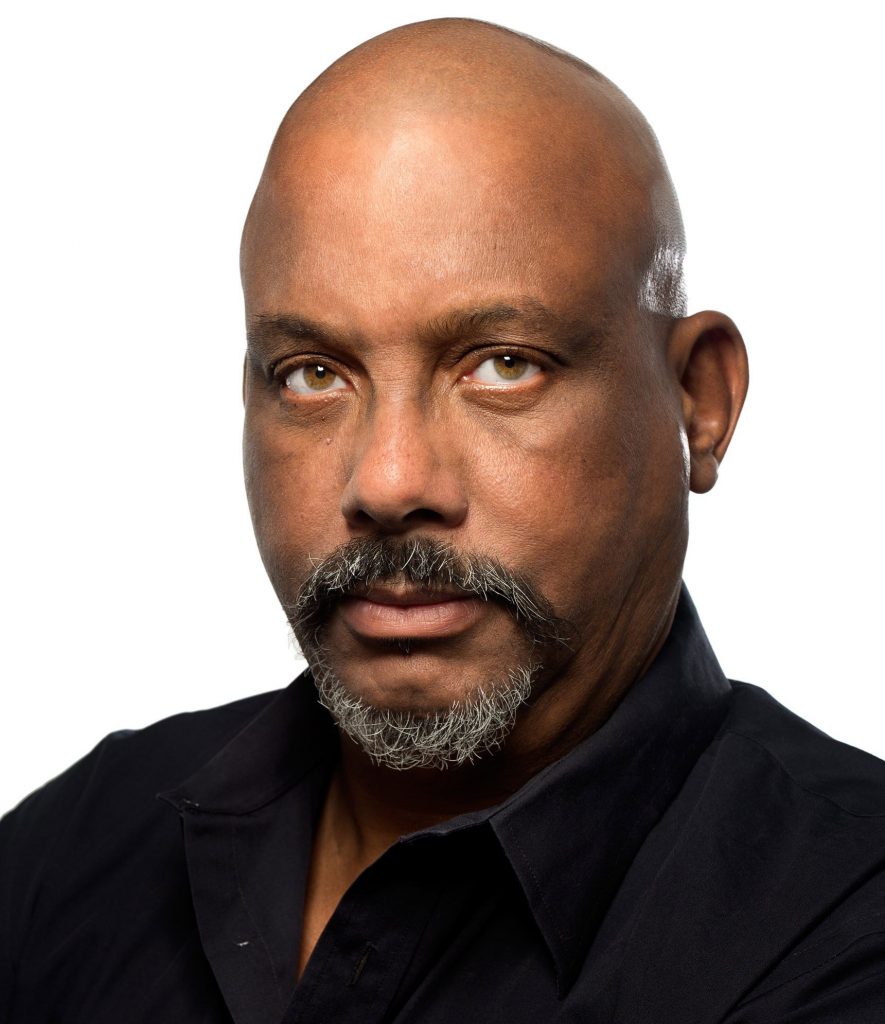

BETWEEN February 9 at 8.30 am and February 22 at 10.32 pm, I photographed calypsonians backstage at six calypso tents this Carnival (http://ow.ly/zgXd30qkCwu).

That experience gave me an unusually intimate look into how calypso tents operate in 2020.

What sustains the business of calypso performance in TT, the land of its creation, is what built it in the first place – the determination of calypsonians to perform their work.

There is a surprising range of people showing up to sing.

Young women in their twenties would casually mention that they had been singing calypso for 12 years. That suggests a major success story for calypso in the Junior Calypso and Junior Soca Monarch competitions.

But then the young performers grow up. What they find in professional calypso is a wasteland where there was once abundance.

I’d drifted away from covering calypso for almost two decades. Nobody really wanted reviews of tent presentations any more as they devolved into set lists with cheerful commentary. Demand for photographs of calypsonians for editorial use bottomed out to near zero as the marketability of soca artists began to soar. Making money writing and photographing Carnival has always been marginal, but serious journalistic consideration of, and engagement with, calypso dwindled in the face of general lack of interest.

Some of this was the fault of calypsonians themselves, who after, confidently striding through more than a hundred years of Carnival, began to think of themselves as invincible. Tents that opened their doors right after New Year’s would run right up until Carnival Saturday, creating massive traffic jams outside their halls as crowds gathered to hear the lacouray. Tent clashes, which brought the best of each participating tent into creative conflict with their rivals were so huge that only the Grand Stand could accommodate the massive crowds. There were ticket scalpers.

Calypsonians then chose to lustily excoriate the politically ascendant Indian population, confidently cutting their audience by half, even as a new generation chose to experience their Carnival music in parties fuelled by live bands and DJs.

Today, tents will often stage a show in a one-to-one ratio of cast and audience. Government subventions are both overt, through direct funding from TUCO, and abstract, as city councils and regional corporations pay for the staging of a free show for their constituents.

This largesse has not been without cost to the art form. In any business, there is a delicate relationship between investment, audience and product. A dramatic change in one always has an equivalent effect on the others.

Calypso, as any practitioner with experience in the art form already knows, is beyond crisis and approaching collapse. Shows are intermittent and performance schedules are sketchy. Lyrical ambition is compromised. Music hews to a formula that desperately needs inspiration. Staging is uninspired and often brutally minimalist.

What we see and hear at the Calypso Monarch finals, often the only calypso that many will hear for the season, bears little relationship to the songs that excited audiences during the savagely truncated season.

But calypso must survive. The tradition of the griot is deeply embedded in our culture and our creative expression, even as its creative tradition has become a dogma of repetition. Our music deserves better. Our calypsonians deserve better.

Without subventions, there is no institutional architecture or business model that allows the successful staging of a traditional calypso tent in this country.

Because there are subventions, there is little incentive to explore alternative models for calypso’s sustainability.

So every year, without fail, the calypso chicken eats the calypso egg and the public is invited to view the inevitable result.

Mark Lyndersay is the editor of technewstt.com. An expanded version of this column can be found there.

Comments

"Wither calypso"