Rise of the magnificent Red House

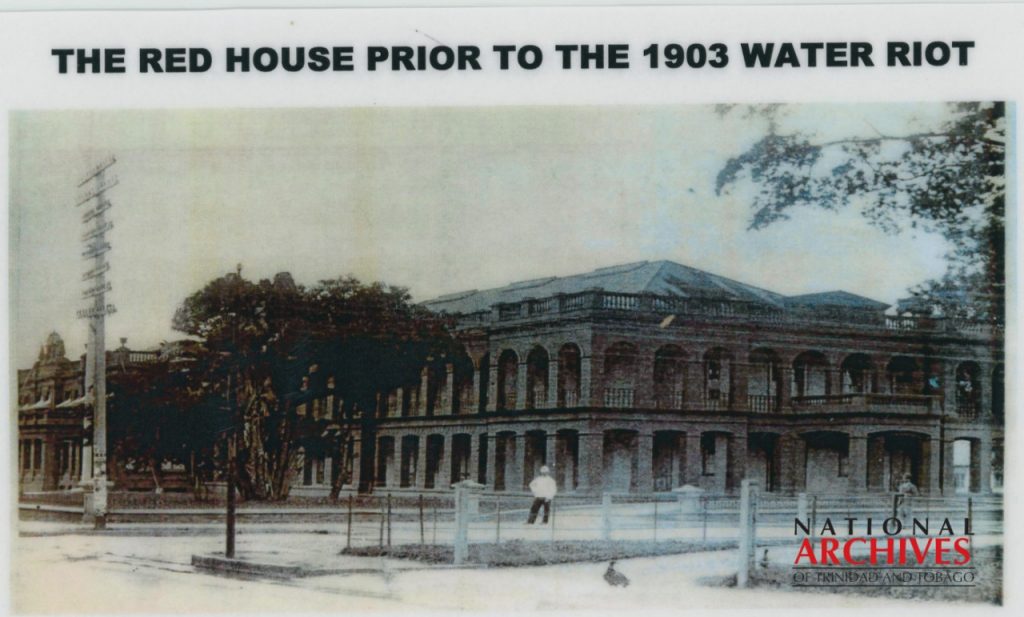

When Governor Col Sir Henry MacLeod laid the cornerstone of the new government buildings on February 15, 1844, the building wasn’t red.

Nor was it one building, but two, joined by a colonnade: Prince Street ran between them.

Though it’s now been restored to its place as the grandest public building in the country, the beginnings of the Red House were inauspicious. Its early days saw the first accounts of what became recurring themes of neglect, near-collapse, and being the target of protest.

In 1846 the Trinidad Spectator scoffed that the interior of the building, still a work in progress, was “monotonous and gloomy,” and from outside, its unplastered brick looked like a factory. That year too it was discovered that the beams were not strong enough to support the roof, and the whole structure might cave in.

The designer died – he was Richard Bridgens, Superintendent of Public Works – and the treasury ran out of money before the buildings were finished. Governor Lord Harris moved into his office anyway; and was there in 1849 when citizens stoned the building, upset that debtors were to be treated like common criminals.

Late in the century, the government buildings were finished and embellished, possibly by Daniel Hahn, Chief Draughtsman of the Public Works, then painted red for Queen Victoria’s diamond jubilee in 1897.

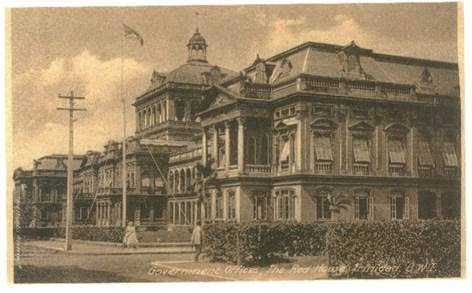

Hahn worked on the restoration after the 1903 fire, set by someone in the crowd protesting against the ordinance on water rates that the legislative council was about to debate. Sixteen people were shot dead in the riot, and the Red House was gutted – but didn’t burn down.

It was outside the Red House that Britain’s union flag was lowered at midnight for the last time in August 1962, as TT became independent.

It was the centre of a literal battle for democracy three decades later when the Jamaat-al-Muslimeen stormed the building in July 1990. Afterwards, a bullet hole in one window of the chamber marked that week-long siege more poignantly than the eternal flame outside.

Then the Red House came under threat from the elements. The only part not damaged by water was the dry fountain in the rotunda. By the early 2000s, sittings of Parliament might be punctuated by chunks of plaster falling from the ceiling. There was also a fire hazard – but the dangerous wiring couldn’t be changed until the roof was repaired.

Full-scale restoration went ahead at last, but was halted in 2013 when bones were found beneath the foundations: they were those of members of the First Peoples, centuries old. Battles – though possibly ritual ones – were said to have been fought on that spot in those times.

The site of the Red House has always been a place of confrontation, the heart of the country, the seat of power.

Comments

"Rise of the magnificent Red House"