Psychology of adoption

This is the final part of the Beyond Blood series

Kirsten MacLean's Kalinago identity crisis and Ron Julien's acting up in adolescence shows behaviour typical of adopted children.

Julien stole his sister's watch set and tossed it down a manhole, out of a feeling of powerlessness and rebellion.

Though he loved his adoptive family, he longed for connection to his birth parents. Both he and MacLean felt like the outside children in their family, lacking a genuine sense of belonging.

Newsday spoke with Dr Varma Deyalsingh, secretary of the Association of Psychiatrists,

about the psychological issues adopted children can experience.

He suggests adopted children and their families begin psychotherapy early so the child can develop coping skills to deal with their feelings as they arise. Julien was put into both psychological and church counselling.

"It gives them a safe space to normalise these feelings. Peer support groups are also a great resource, as it allows children who are adopted to know they are not alone, and they can share their experiences and feel seen and heard," he said.

The adoption process does not end when a child is placed in a home. It is only the beginning, as parent and child work towards negotiating their new relationship and manage their expectations.

"Some parents may want to overcompensate, and the child may grow up spoilt and lacking independence. Some parents may not be prepared for normal teenage resistance, and feel betrayed when these young persons act up. Some even want to gave back the child."

The adopted child will experience different emotional issues, depending on their age and life experience. In Julien's case, as he was abused, he had difficulty expressing himself in the beginning, and his acts of rebellion got him put out of his home.

Julien told Newsday in an interview he started stealing out of rage.

"I can’t fight with them. I can’t do nothing. I could only get banned, so things that I knew they liked, I stole...These things had a domino effect on me. They used to say, ‘You’re just like your father.'"

Deyalsingh said some children are afraid they will be sent back, and have fears of abandonment and anxiety.

Adopted children may also feel isolated from their peers, as their background is different from other children's.

They may have an inferiority complex – a feeling of inadequacy. They may compare themselves to other people, put themselves down or be hypercritical of themselves.

Both Julien and MacLean actively sought connections with their biological families – MacLean as an adult, and Julien as an adolescent. Deyalsingh said sometimes adopted people feel guilty if they need to search out their biological parents.

Attachment theory

Psychosocial rehabilitation specialist Kendra Cherry,

in a Verywell Mind article, Bowlby & Ainsworth: What Is Attachment Theory? The Importance of Early Emotional Bonds (https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-attachment-theory-2795337) discusses the various forms of attachment in childhood.

The pre-attachment stage is from birth to three months. The child does not show a specific attachment to a caregiver. An infant starts to show preference for a primary and secondary caregiver between six weeks and

seven months. This is called indiscriminate attachment. Infants begin to develop trust in that caregiver during that time. Between seven and 11 months an infant forms a strong attachment to a caregiver. This is called discriminate attachment. After approximately nine months, children begin to form strong emotional bonds with other caregivers such as grandparents and older siblings, called multiple attachments.

"The central theme of attachment theory is that primary caregivers who are available and responsive to an infant's needs allow the child to develop a sense of security. The infant knows that the caregiver is dependable, which creates a secure base for the child to then explore the world."

However, children adopted after six months old have a higher risk of attachment problems. Deyalsingh said children who were not able to attach to a caregiver in the first two years of their life have greater difficulty fitting in.

"Attachment theory explains (that) a child may learn there is someone out there for him to fill his needs. This provides a level of comfort to the child and neural scans show cuddling and kissing a newborn causes a burst of oxytocin, a neurochemical, which generates a feeling of affection and attachment."

Abuse

Previous abuse can take a toll on adopted children's self-esteem and self-perception, sometimes making them feel unworthy of love or even of a new family. Deyalsingh said such feelings of self-doubt and worthlessness can make them act out in many ways.

"Some may have decreased performance in school, act aggressively towards their peers or even new siblings, some may fall into feelings of depression with associated self-harm behaviours."

Effects of previous trauma on adopted children

Many children who are adopted have experienced early trauma as a result of abuse, early deprivation and neglect, or institutionalisation.

Children and youth who have been removed from their birth families and placed in foster care, particularly those who have had multiple placements, have often experienced chronic or complex trauma.

Even for children whose early life experiences may not seem to have included significant traumatic events, being removed from their families of origin can be traumatic.

The effects of trauma on development vary from child to child and may not always be evident until later years

Identity

Some adopted children have questions about their identity, yet may not get answers, like MacLean, who wondered what her father looked like.

MacLean travelled to Dominica to meet her family. She desperately wants to learn about the Kalinago – Dominican First Peoples – culture. Even little things like making cassava dumpling and pumpkin bread.

"I really would like to learn about my heritage, my culture...I would have liked to have known if my father had black in him. I would like to know if I am full-blooded Amerindian. Certain things would be dead to me," MacLean said.

Some adopted children question why they were given away.

Deyalsingh said identity formation is an important part of child development.

"Identity formation begins in early childhood and moves to greater prominence as a child reaches adolescence. Identity formation forms the building blocks of a person’s adult identity."

Self-esteem issues follow identity issues. Some adopted people may view themselves as different, unwelcome or rejected. Some of these feelings may result from the initial loss of birth parents and from growing up away from birth parents, siblings, and extended family members.

Interracial adoption

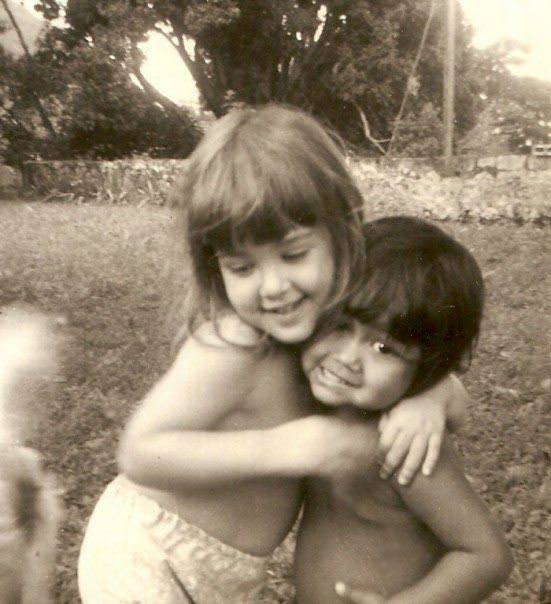

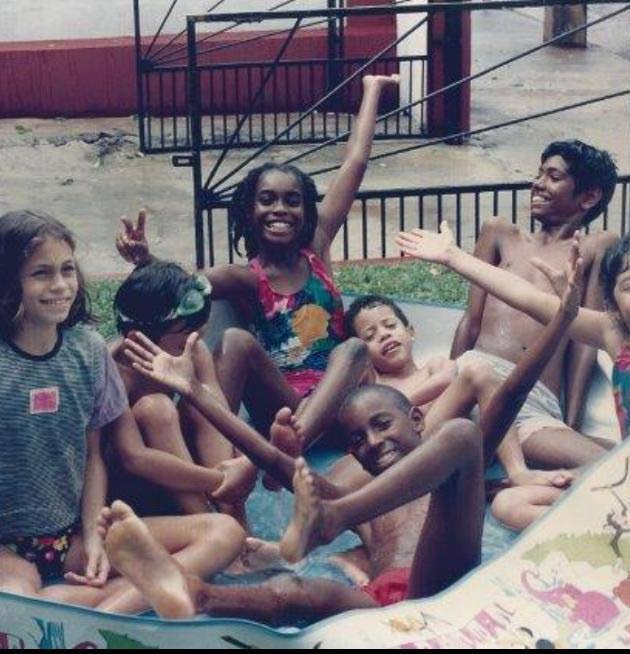

MacLean's adoption was interracial, a

s she was a brown-skinned Kalinago baby adopted by a white Trinidadian family.

“But I felt like a sore thumb – a black child in a white family. I always had to answer questions. I was always put on the spot. I had to dodge the questions. I formed certain things in my head to cope with the reality of being adopted.

“I am adopted; that’s it. I dealt with it like that, but I would not tell anyone I was adopted,” MacLean said.

In interracial adoptions, Deyalsingh said, parents should prepare their children for possible racism and questions on identity. Parents should establish open communication with their child about their heritage and try their best to expose that child to that part of their identity.

"Parents sometimes worry about their adopted child assimilating and as such try to avoid exposing their adopted child to their original culture, in an attempt to not confuse them. That does more harm than good, as the child will inevitably be confronted with issues of racial identity. It is unavoidable. It is best that parents create an open environment where the child can inquire without fear of judgment or hurting their adoptive parents.

When to tell a child they are adopted

Deyalsingh suggests telling a child they are adopted during pre-school, as the child does not yet understand reproduction and must first understand that they have a birth mother.

"Telling a child his or her adoption story at this early age may help parents to become comfortable with the language of adoption and the child’s birth story. Children need to know that they were adopted. Parents’ openness and degree of comfort create an environment that is conducive to a child asking questions about his or her adoption."

Side bar

Deyalsingh's suggestions on how to help make the adoption transition go smoothly:

Talk to your child, ensure that the child knows they can talk about anything, including their birth parents.

Make sure that the child has their own space – big or small – that is just theirs.

It can be helpful to create a book about their history so if they have questions you can tackle them together.

Don't rush the integration process, follow the child's cues, don't overwhelm them with activities.

Prepare yourself and family for the challenges. Explain to your kids that this process may not be easy and know that their new sibling may act out, or become sad and withdrawn.

Create bonding activities such as planning activities you can do together and as a family, but don't overwhelm them with too much.

Past abuse of an adopted child can create barriers to a child's integration to their new forever family. Abuse and neglect can cause a child to have a mistrust of his or her care givers. They may feel they can only trust themselves, which makes them guarded and self-isolate.

Older adopted children who leave their original would feel some level of grief related to the loss of their birth parents.

Comments

"Psychology of adoption"