The destruction and death of our cities

“The city is a teenager, with a certain formation already; character, personality, the bones are here. We’re sending this adolescent to finishing school.. These were the recent insightful words from architect Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk in a highly recommended podcast interview with the Harvard University Graduate School of Design.

The dean of the University of Miami’s School of Architecture for nearly two decades, she is one of the founding members of a movement in urban planning and design known as the New Urbanism, a movement of which I am an advocate.

In a lecture to the Congress of the New Urbanism in 2015, Duany described the power of architecture as the “power of camouflage.”

The opposing view sees it as the power of self-expression, or architecture as a “peacock” meant to stand out.

Plater-Zyberk and others, like her husband Andrés Duany, promote an architecture and urban design that respects context, the vernacular, and public tastes.

New urbanism, as applied to cities, is based on a deep respect for the existing, and the qualities that define urbanism: the vibrant and intricate intermingling of people and activity in public spaces. Architecture is integral and should serve to reinforce urban character and coherence. The city is the only place where one can experience urbanism in its most grand, intense, intimate, and authentic way.

Many planners and architects, and those who wield similar influence in our midst must see these qualities of urbanism and socialisation on the public streets of a city as abhorrent and corrupting. The existing city must be an unfortunate menace standing in the way of their vision. For it is exactly the existing that their designs eliminate.

Intentional or unintentional, the effect is the same. Their approach shows a deep disrespect for the city as a bubbly teenager in need of better social skills. It shows a paternalistic attitude that seeks to send the adolescent under the plastic surgeon’s knife and, through intense sessions of psychotherapy, to remove all traces of warmth and affection, to create an entirely new anti-social child in the vein of their modernist urban design dogma.

Their vision must be a place where rejection of public life is the norm. Where buildings are seen as isolated entities with no role in adding to the coherence of the neighbourhood as a whole.

A recent conceptual plan for a new development in uptown Port of Spain, on a prime piece of land in a desirable location, left me outraged and frankly demoralised. A well-designed project at this location could be a game-changer, serving as a catalyst to improve the immediate vicinity, which is vibrant, yet undervalued and a bit unrefined.

The designers have instead proposed two towers that sit in the middle of the sizeable lot, surrounded by a sea of surface car parking, and some token green spaces with the leftover land in this to-be-gated compound.

The large distance between the sidewalk and the buildings is rationalised as a desire to protect the building users from exposure to the undesirable public roadway. The positioning, form, and orientation of the buildings serve to maximise the perceived benefits for the private inhabitants, with no apparent consideration of the impact on the public street around it, nor the characteristics of the surrounding buildings.

In other words, no attempt to conceptualise the development as a unifying and uplifting addition.

This design mentality – being replicated in Arima, Chaguanas, and San Fernando too – replaces the urbanism of the city with a vapid nothingness that scorns the vitality and life that a street and sidewalk are supposed to foster, and eschews the role that private buildings – which give definition to public space – must play in this process of social interaction.

Offending designers must forget that building inhabitants have to leave the confines of the property, as regular people do, and enter the very public spaces that their projects have caused to deteriorate.

Of course, the project perfectly fulfils the requirements by the regulatory agency, the Town and Country Planning Division, since few or no urban design or architectural design requirements are currently imposed. Despite the well-established economic, environmental, social, and health benefits of pedestrianism, the regulations simply are not meant to create a city with lively, walkable streets.

As more projects like this get built in our urban centres – the only places where one can experience true urbanism – we will have succeeded in destroying a way of living that many love, cherish, and yearn for.

These are the same qualities and liveliness that millions of tourists flock to San Francisco, Tokyo, Casablanca, and Barcelona every year to experience. And, ironically, the same types of places that many of the offenders will cite as models of urbanity, or escape to – when they have had enough of the soulless places whose creation they have fostered right at home.

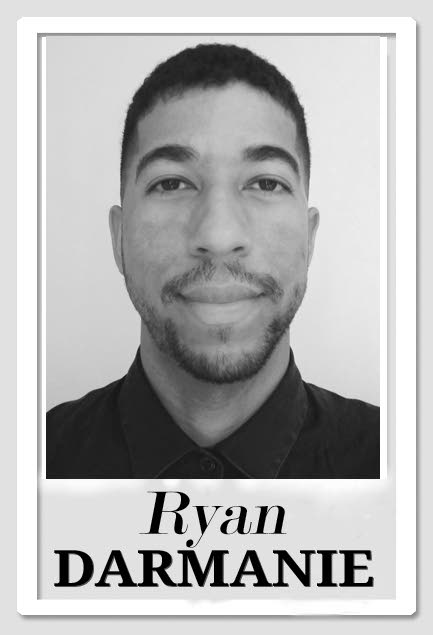

Ryan Darmanie is a professional urban planning and design consultant, and an avid observer of people, their habitat, and the resulting socio-economic and political dynamics. You can connect with him at darmanieplanningdesign.com or email him at ryan@darmanieplanningdesign.com

Comments

"The destruction and death of our cities"