Hero’s journey from Hitler to Africa overshoots target

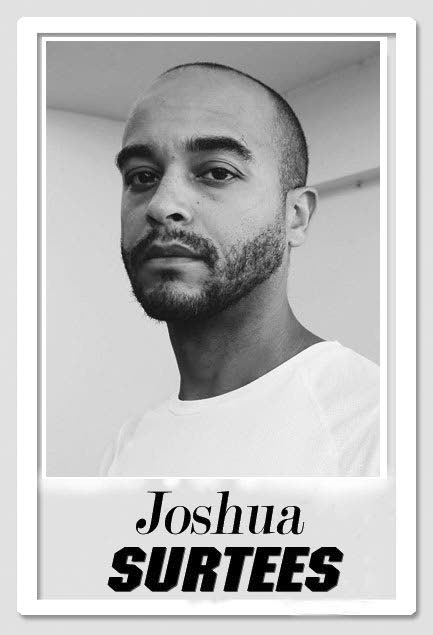

Josh Surtees

The TT Film Festival opens on Tuesday with another ambitious Trinidadian production. Hero, a film about the extraordinary life of WWII pilot Ulric Cross, follows the magnificent Green Days By The River, which blew audiences away in 2017.

It again takes us back to the mid-20th Century, but unlike Green Days which delved inside Trinidad’s rural colonial underbelly, Hero, directed by British-born director Frances-Ann Solomon, will confound those expecting another rich slice of West Indian nostalgia. It will also leave those who, like me, thought they were about to watch a war movie, somewhat perplexed.

Hero is really a film about Africa. It hastily pushes through Cross’s early life in Belmont, where he was born in 1917 into a middle-class family – “not black, not white, but sandwiched in between.” It skims through his early encounters with academia, literature and tragedy. Then it intersperses archive footage of wartime London with scenes of the handsome uniformed young Cross, played by Nickolai Salcedo, bonding with other eager West Indian recruits ready to drop bombs on Hitler.

Hitler is swiftly defeated, Cross gets a job at the BBC, meets the love of his life, Anne, is introduced to Caribbean intellectual heavyweights like CLR James and George Padmore, and suddenly we are witnessing the birth of African politics with Ulric (now a trained lawyer) absconding to a summit in independence-era Ghana, where he’s wedged into the role of catalyst, revolutionary, mediator, diplomat, agitator, organiser and friend to leaders like Nkrumah and Lumumba.

The extent to which the film fictionalises Cross’s part in liberating Africa from European colonisation is up for debate. It does not purport to be all fact, but rather, "inspired by true events," like biopics tend to be. The question here is, if the film is intended to educate people about the endeavours of a Caribbean hero like Cross, shouldn’t it provide more detail, more focus, more accuracy?

Instead, in attempting to do an awful lot – the real-life Cross appears in family footage shot before his death in 2013, his wife Anne is interviewed in close-up pieces, and their daughter Nicola is played by a woman with an American accent – Hero ends up a somewhat embellished Wikipedia entry. At times it’s even a spy movie. Snippets of a courageous, free-willed life spent in England, Cameroon, Tanzania and Trinidad flash by, with scenes rarely lasting long enough to absorb. It moves at a fast pace but with a stodgy rhythm.

Still, there are intriguing moments in Hero, not least those featuring CLR James, played by Joseph Marcell, that reveal how the British establishment viewed James as a threat.ss

Seeing the real-life Anne captured on screen is a coup – perhaps the best thing about the film. She embodies the spirit and wisdom of all those radical, strong, progressive white women who fell in love with Caribbean men and didn’t give a damn what society thought. She was ahead of the curve that helped make Britain a cosmopolitan place, perhaps the most integrated and multicultural white society today. Pippa Nixon, who plays the younger Anne – wooing Cross in post-war London, cussing him when he deserts her, reconciling, fuelling his adventurous spirit – does a decent job portraying the modernness of her personality, though her millennial accent and phrasing seem at odds with Salcedo’s more formal tones.

It was vital that this film was made, not just for its content, but to continue propelling the forward momentum of Trinidadian cinema. Green Days was a pivotal moment that showed the world the Caribbean can produce large-scale, exquisitely-costumed, well-acted movies with lush cinematography, after years of low-budget, experimental output. That Hero doesn’t quite follow through is mostly because it doesn’t know what it wants to be. That’s not meant as harsh criticism, but rather an indication that Trinidadian cinema as a whole still does not know what it wants to be.

How the film will be received depends on the level of interest Trinidadian audiences have in pan-Africanism.

Attitudes here die hard. Sixty years on, despite much Caribbean flattery of Africa – the conspicuous celebration of its look, feel, sound and culture – the truth is that the connection was severed long ago. Very few Caribbean folk have been to Africa and very few have any real desire to go. It is not their motherland.

In Hero, we glimpse how Britain used Caribbean people “like cattle” for the war effort, then discarded them. Still, Cross felt England was home, while Africa was an exotic, riotous adventure. That cleaving to European sensibilities has not dissipated.

In an increasingly inward-looking, xenophobic Trinidad, Hero may struggle to convince so-called patriots of the value of heroism, presented here in a hardworking portrait of a true man of the world.

Comments

"Hero’s journey from Hitler to Africa overshoots target"