The great books

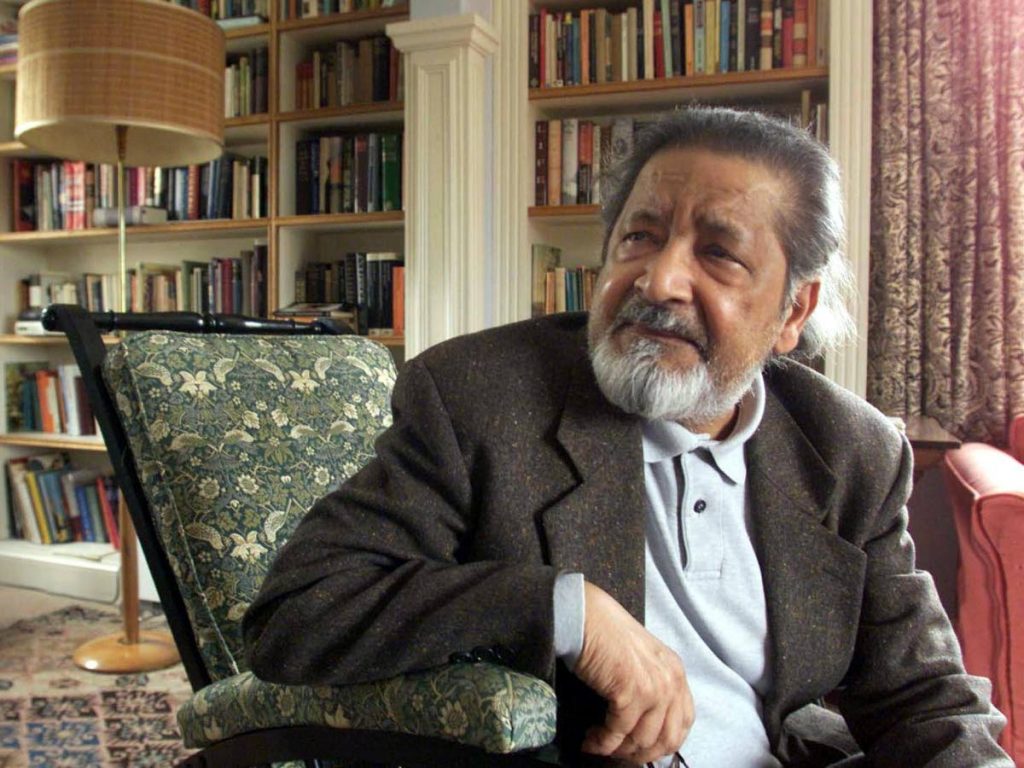

HE WROTE dozens of books, yet, in a sense, VS Naipaul spent a lifetime writing only one thing: his own story.

After the early novels, in which his keen ear for dialogue, technical mastery of prose, and talent for comedy emerges triumphantly; after the magisterial A House for Mr Biswas, in which the title character’s profound vulnerability sheds light on the fate of Trinidad as a new nation; after the novels set in London, in which he sought to prove he could write about anyone anywhere and in wintery tones too; after In a Free State, which saw him push against the margins of the novel; after the ambitious books of sex, violence and Black Power; after The Enigma of Arrival, a work that has not lost its power to confound; after the forced yet sometimes beautiful sequences towards the end of his fiction; and the turn to stunning reportage and travel writing, in which he spoke truth to power and offended in equal measure – after all of this we are left with, in effect, the most astonishing autobiography in English letters.

On August 11, on his deathbed in London, Naipaul took comfort in Tennyson’s poem Crossing the Bar, with its tide that “turns again home,”

For some, the question is: which home?

The books provide the answer. They can and should be read as one. They tell a tale that always leads back to Trinidad. He remains a native son.

His prose is famously crystal clear, but Naipaul the man was as messy as they come.

Fittingly, each publication was a different Carnival costume. Always, a different aspect of the author was revealed beneath each surface, even when the subject matter took him to places like India, Africa, the American South.

“An autobiography can distort; facts can be realigned,” Naipaul once declared. “But fiction never lies: it reveals the writer totally.” He proved himself right.

The opening sentence of his novel The Mystic Masseur (1957), his first published book, tells us as much about his ambition as it describes the title character: “Later he was to be famous and honoured throughout the South Caribbean; he was to be a hero of the people and, after that, a British representative at Lake Success.” We follow Ganesh, a masseur renowned for his healing powers, as he transitions from mystic to entrepreneur to author and politician. The book is light-hearted, but not light, satirical, but not bitter.

Next came the short and entertaining novel The Suffrage of Elvira (1958), which follows a local election in rural Trinidad. Despite its slapstick comedy, it is regarded as one of the first serious attempts to fictionalise the impact of multiculturalism on the democratic process. Lloyd Best said it was Naipaul’s best.

Miguel Street (1959) followed. Famously begun in June 1955 on non-rustle BBC studio paper when Naipaul worked on the Caribbean Voices radio programme in London, its publication was delayed for marketing reasons. Its interconnected stories, with characters such as Hat and Bogart, are among his most memorable. Yet, for all its lambent qualities, the narrator flees Miguel Street at the book’s end. According to Laurence Breiner, professor of English at Boston University, this ending is significant.

“It is nearly irresistible to regard the narrator as Naipaul. The adult narrator tells the stories in standard English,” says Breiner. “But when the same person speaks, as a child within the narrative, he uses creole. In an autobiography this would be a crucial and problematic transformation of the protagonist. Here no attention is drawn to it at all.”

If it is tempting to see Naipaul as the narrator in Miguel Street, it is impossible not to find him in his next book.

A House for Mr Biswas (1961) follows its titular character, who has ambitions to be a writer and to own a home of his own. Biswas seeks to escape a life in which one remains, “as one had been born, unnecessary and unaccommodated.” The title character is modelled after Naipaul’s own father, Seepersad, a reporter at the Trinidad Guardian, from whom he got his desire to write and, arguably, his lifelong passion for journalism.

The book anatomises Trinidad society against the backdrop of a father-son relationship. Its prose approaches pure poetry. Naipaul writes that the Biswas family would soon fall prey to the vagaries of memory; their experiences will commingle or be forgotten:

“Occasionally a nerve of memory would be touched – a puddle reflecting the blue sky after rain, a pack of thumbed cards, the fumbling of a shoelace, the smell of a new car, the sound of a stiff wind through the trees, the smells and colours of a toyshop, the taste of milk and prunes – and a fragment of forgotten experience would be dislodged, isolated, puzzling.”

In his next fiction, Naipaul would cover new ground. Mr Stone and the Knights Companion (1963) features only white characters and is set entirely in Britain. While this elegant and enjoyable book was an exercise designed to prove his range, it arguably also tapped into his anxiousness to divorce himself from his Trinidad roots. If that was the case, the divorce did not last long.

A Flag on the Island (1967), with its outstanding short story The Nightwatchman’s Occurrence Book, would take him right back, as would the wintry The Mimic Men (1967), which followed a Caribbean politician in exile in London. Unlike his previous books dealing with politics, the tone is not comic, there is no plot. Eric Williams described its dense passages as “harsh but true.”

Williams’s words could have also described In a Free State (1971), a novel that strings together separate narratives. While Naipaul should be praised for seeking to push the limits of the novel here, the work is more a collection of sequences than a book proper. Its central novella is a strange road-trip narrative through a fictional African state featuring a gay character who, at the work’s climax, is abruptly assaulted.

Violence, and problematic depictions of violence at that, would also feature in Guerrillas, an attempt to fictionalise the case of Trinidadian black activist Abdul Malik or Michael X, whose band of associates murdered British socialite Gale Ann Benson. The book contains strong descriptions of the Trinidad landscape. However, its post-modern aspects, such as a novel within the novel, are tone-deaf. Naipaul once wryly suggested the book could be regarded as comedic when read in his voice.

Yet here is the book’s climax, the brutal murder of the Gale Ann Benson character: “Sharp steel met flesh. Skin parted, flesh showed below the skin, for an instance mottled white, and then all was blinding, disfiguring blood.”

Writer Paul Theroux describes the novel as “a shroud slowly unwound from a bloody corpse.”

The book’s female characters are problematically flat. The tantalising possibility of Benson’s being a spy – later portrayed in a 2008 film – is not allowed. And the female body subjected to violence and humiliation in a manner that feels moralising. This is more disturbing when coupled with Naipaul’s later declaration that women writers are inferior.

“There is strong evidence from the biographical details he has revealed, from the ranting of his detractors and from his treatment of some of the female characters in his books that he resembled the profile of a misogynist,” professor of gender and cultural studies at UWI Patricia Mohammed says of Naipaul. “But I would argue he was committing himself to his own brand of honouring truth – through a Trinidadian admission of one’s innermost foibles; an admission that misogyny is alive and kicking.”

A Bend in the River, published four years after Guerrillas, would be set in an unnamed African merchant post. The book is full-bodied, containing some of his finest prose. Its focus on negative aspects of African nationhood, as well as its unvarnished picture of post-colonial African society, have been interpreted as an indication of his neo-colonial views. Yet, for all its uncomfortable passages, it is perhaps more fatalistic than pessimistic. That fatalism is summed up by its opening: “The world is what it is; men who are nothing, who allow themselves to become nothing, have no place in it.”

Naipaul’s major novel in the 1980s was The Enigma of Arrival (1987), a work as confounding as the de Chirico painting which gives it its name. Described by Derek Walcott as “scarred by scrofula,” the book was nonetheless praised by the Nobel committee, who described it as Naipaul’s masterpiece, “an unrelenting image of the placid collapse of the old colonial ruling culture.” Another gay character, Allan Grey, meets a sad end. The book follows no plot to speak of, or, if there is a plot, it is the slow discovery of the Wiltshire countryside. However, its blurring of the lines between fact and fiction, its self-reflection, and its final act – in which a key event is revealed which brings Naipaul right back to Trinidad again – make it one of literature’s most tender acts of anamnesis.

With A Way in the World (1994), Naipaul seemed to be going over already-covered ground. So too in Half a Life (2001) and its fatigued sequel Magic Seeds (2003). While he made a career of revisiting the same subject matter – namely, his life in Trinidad – in these works the charisma of early Naipaul is not apparent. The Enigma of Arrival is, therefore, in some respects, the final word.

Here is how that novel’s fictional narrator, a writer who strongly resembles Naipaul, sums up the origins of the book eventually held in the reader’s hands: “Death was the motif; it has been the motif all along… Faced with a real death, and with this new wonder about men, I laid aside my drafts and hesitations and began to write.

Comments

"The great books"