The grounding of Anthony Joseph

MARK LYNDERSAY

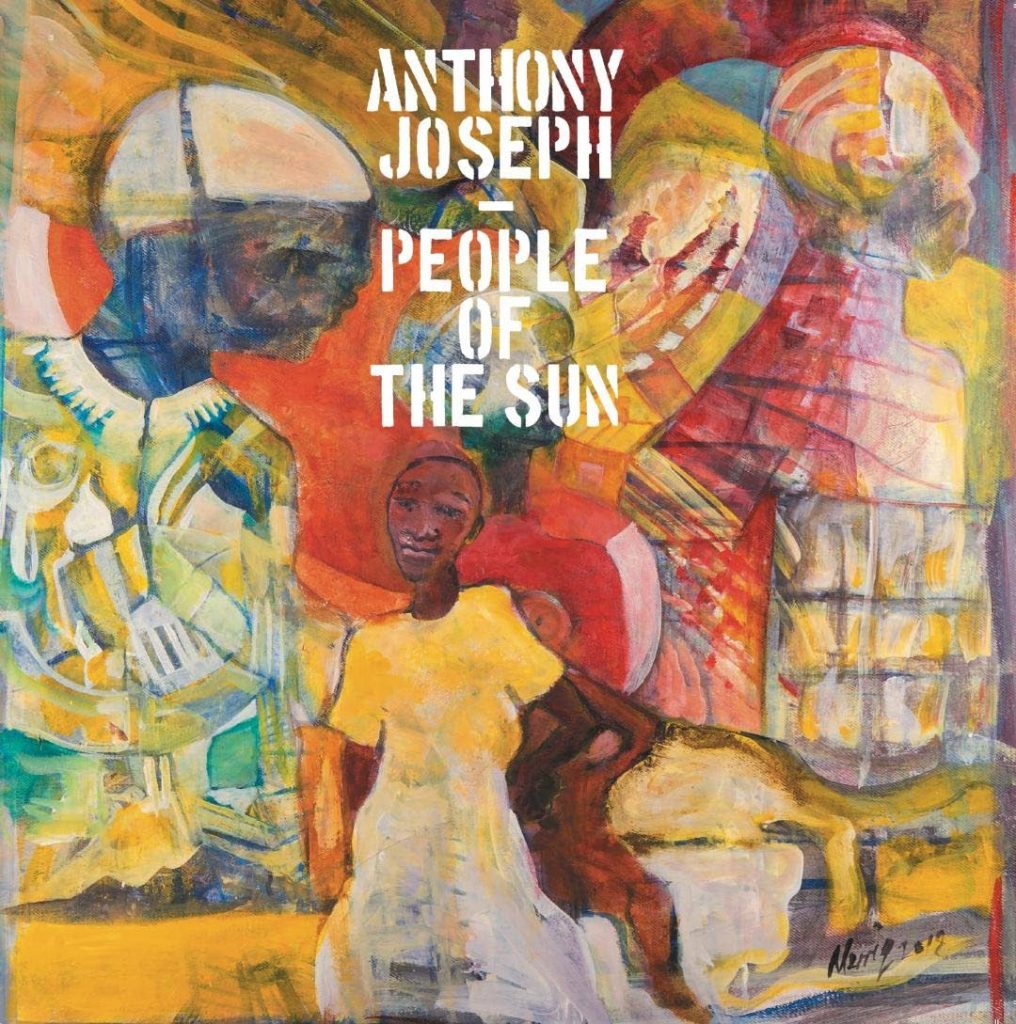

PEOPLE of the Sun is, whether poet Anthony Joseph knows it or not, the peak of a trilogy of albums that have seen him circling in ever more incisively on a vision of TT that is nostalgic, brutally honest and stunningly engaging.

The first part of this work begins with Time, a neo-funk album that emerged from a collaboration with Meshell Ndegeocello, which addressed issues of being black, from Caribbean and being aware of all that means in modern society (http://ow.ly/ZoJD30ljmRf).

That album tasted deeply of the bitterness of slavery and institutional oppression, but found its fullest flower in Michael X (Narcissus), a dense eight-minute poem exploring the fierce legacy of Abdul Malik. It’s a work full of questions and confusion, a man trying to understand the world he was born into but which must seem alien from the distance of Europe. It was also a turning point for me in appreciating Joseph’s craft; unflinching words, atmospheric storytelling, a definite and unmistakable perspective.

On Caribbean Roots, the poet dispenses with worldliness to become specific, daring his international audience to consider darkness and dust in these islands where hope thrives in spite of observed reality.

I began my review of that album during a time of personal upheaval, and never published it before now (http://ow.ly/NTj430ljmSd).

Joseph drilled down into black Caribbean experience on Caribbean Roots, becoming ruthlessly specific and detailed in his cross-examination of history and remembrance. I have no idea what foreign listeners made of that album, but they could only learn from its insightful storytelling and visionary, sometimes hallucinatory descriptions of life experiences of these islands.

They’re likely to have even more problems with this one, on which the poet exercises his potent gift for colourful narrative and rich awareness of cultural detail.

Or they might not.

Of the three albums, this is the most powerful musically. I needed to reach out to the poet for a lyric sheet after realising that I’d listened to the first pass of the album without paying any attention to the words. On the musical level alone, it’s a riveting work, with beats and collaborations that anchor the work fully in local musical style and using its TT creators for more than window-dressing.

The core band, David Bitan on drums, Modupe Folasade Onilu on percussion, Florian Pellissier on keyboards, Andrew John on bass, Kiwan Landreth-Smith on guitar and Jason Yarde on sax and anything he can lay his hands on, apparently, lay down a bed of grooves that’s pleasantly surprising in its range and complexity. Critical moments soar on strings supplied by Napa musicians and brassy horns straight from Ed Watson’s notebook.

The album opens with a remarkable groove, Milligan, The Ocean, sent soaring from its first notes with a haunting vocal introduction by Ella Andall, whose choral scatting underpins the entire work, a seductive tale of Milligan Benji, another of Joseph’s doomed protagonists who flail their way through the temptations, tragedies and the mystical soul surrender that are the hallmarks of his best work.

And early on the fifth day he met a merman.

And he asked the merman, he say, Mister man, where my Iere?

And the merman replied: Iere dissolved in the flood like sugar in saliva, only fragments remain

And Africa? Milligan asked

And to this the merman calmly replied,

Many died.

The album’s commitment to its music as an equal partner with Joseph’s words is hammered home with San Souci (Totem), a number that bounces along with all the eagerness of a 1980s road march, driven by Len “Boogsie” Sharpe’s coolly precise pan soloing for three minutes before the poet says a word.

Joseph is smart enough to use the strengths of his collaborators and even to be influenced by them. Bandit School sounds like the kind of groove that 3canal might have come up with on their own, but for all its enthusiasm, it ends up being one of the weaker tracks on the album.

It wilts when compared with the fearsome intensity of Suffering (This Savage Work), an unflinching love letter to generations of Caribbean women who shelved their lives to do scut work and raise families and extended families.

Joseph has spoken of love and passion, but there’s never been anything as bleak and terrifyingly familiar in these three albums as his breakup song He Was Trying. It’s as sad and painful a love song as you can imagine, an all-too-familiar story of a tolerant wife and an itinerant but charming husband. The poet details “rows of sorrows that had no ending,” limning a disastrous but oddly beautiful relationship that ends in a dark and emotional cul de sac.

On the Move, a dizzyingly adventurous bit of word and music play that bounces words and phrase off sharp horn stings from Yarde and QB with roaming drum snaps by Bitan, doesn’t sound like it belongs on this album, except perhaps as a springboard to another work, one that takes the richly realised music of this one in a more technical direction.

More properly sited is the ethereal Incense Taxi, a fancy of imagination that floats on an arrangement of woodwinds and strings like a candy floss wisp of memory.

People of the Sun and its predecessors, Caribbean Roots and Time, are more than just the work of a poet in fine form exploring the marriage of his words and an increasing comfort with dressing it with music that now uplifts and explains beyond simply accompanying it. This is work that’s both accessible and challenging, something that’s increasingly difficult to accomplish in a world with little time to consider words, far less meaning.

Joseph brings the circle of this exploration of things Caribbean broadly and things TT specifically back to its beginnings with the sharp funk of the title track, led by local soul singer John John Francis. This is a song that could have appeared comfortably on Time, the first album in this navigation of difficult history and painful reality, but it probably wouldn’t have been this triumphal or this celebratory.

“The surface of a thing will never give up its secrets if all you do is ask,” the poet explains on the track.

Those words seem to come now from a place removed from the gentle curiosity of Time and have the urgency of earned authority and experience.

Comments

"The grounding of Anthony Joseph"