Jacob Ross: Master of his craft

JUDY RAYMOND

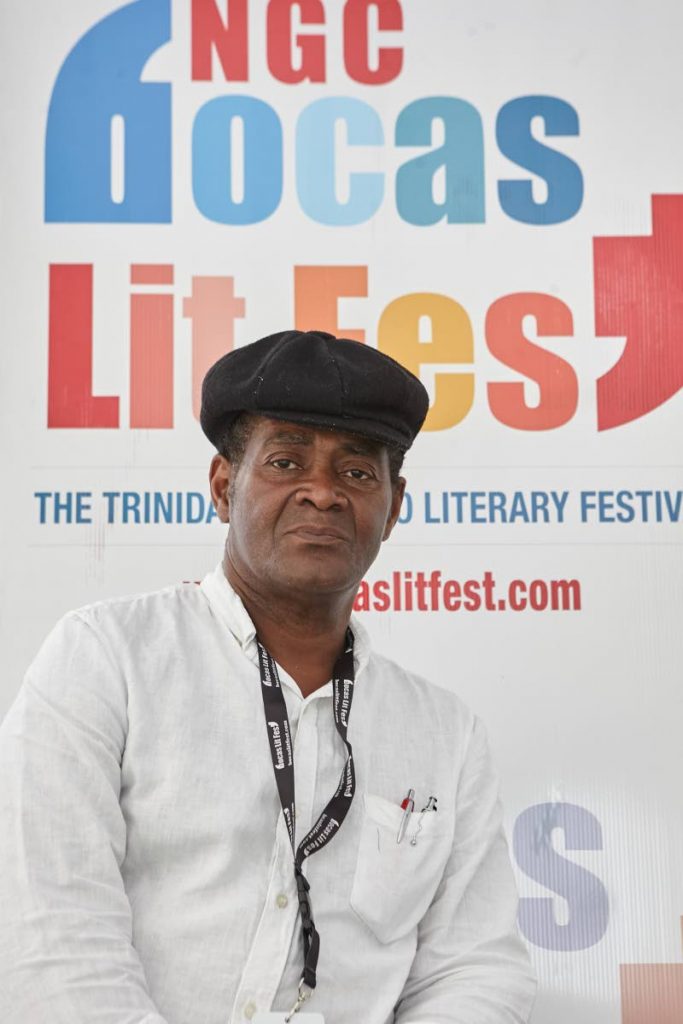

JACOB ROSS looks like a craftsman. Wiry and weatherbeaten, hatted, neatly dreadlocked, he strode purposefully through the NGC Bocas Lit Fest last month. He might have been a sound technician, or a master joiner, or a boatbuilder.

But he’s not any of those things. He couldn’t fix the projector he needed for his workshop on short fiction at the National Library. Luckily it eventually righted itself, as though in response to his schoolmasterly chiding.

Ross is a master craftsman, though. His craft is writing, as he demonstrated in his workshop, dissecting the stories he’d set his class to read for homework, identifying trigger points where the story really begins and tracing the arc of the characters, and how they were changed by the story’s events.

His accent revealing his origins in Grenada and his long years in England, he briskly outlined the techniques he’s devised, stripping narratives down to the framework that gives them shape and makes a story work.

“Write your story, then interrogate it. What does your character lack? Take the story of Cinderella. What does she lack? Not a man,” he said, scathingly dismissing Prince Charming. What she lacks is freedom.

The action needs escalation before the resolution, he said, rephrasing for a Caribbean class: “It has to get worser and worserer.” He revealed the secret of a three-point structure. “It’s a basic idea,” he explained, scribbling on a board, “but it’s magic.”

He’s an editor’s editor, too. One story he chose for the class was good, but far too long. He speedily diagnosed the problem: “That’s just riffing.” As he put it, the writer had talent, but less craft. What it needed was a hard edit – cutting by a third or even half (he admits he’s “pretty ruthless”).

There are engineers in Ross’s family, and he applies similar skills to literature. Perhaps it took years of thinking and teaching to work out the analyses he shares in moments now; or perhaps, given his quick-wittedness, articulated with an acerbic humour, he could always identify the essentials immediately.

It was his intelligence, evident since boyhood, that spared him a life of poverty in Grenada. His stories of country childhoods in the island, collected in Tell No-One About This (2017), and obviously based in experience, offer spare but telling glimpses of that life.

Ross is slightly evasive when asked for an interview, but once cornered, he becomes warm and talkative, his initial caution soon gone.

He was born in 1956 in Hope Vale, in the cane belt. His boyhood was seminal: “It shaped my imagination.” He was one of three sets of twins born to his mother, who had 11 children in all; ten survived. He and his brother Esau, biblically named, were her only children by their father. She was in her 20s, their father in his 70s. A middle-class Barbadian, he didn’t live with them.

But when Ross was ten or so, he was sent to live in a small house about a mile from home with his father, who was going blind. Ross became his eyes, describing the world to his father, and that, he says, led to the importance of landscape in his work. “At 12 I knew words like fuchsia, cyan…He was keen to satisfy his craving for what he’d lost, so I was sensitised to light, shade, patterns, textures.”

His talent was noted by his teachers, among them Jacqueline Creft, Maurice Bishop’s partner, who taught him English. In addition, his father, who lived a frugal, secluded life, was highly educated and taught his son a lot: “He would say, ‘I want to leave you with everything I know.’”

Ross went to the Grenada Boys’ Secondary School: “I was one of the first boys from a peasant background to go to a prestige school.” He and his twin were also regarded with suspicion because they were outside children, but they weren’t intimidated. “We said, ‘We goin’ show them.’”

Young Jacob was an introvert; he didn’t play cricket and football with the other boys. When he visited his mother’s home, then lived there again after his father died when he was 14, he spent his time reading, to escape reality. His mother understood him; sometimes people thought he was her favourite. But it wasn’t that, he says: she saw him as the little one, needing special attention, just as he had had the best of his father.

By then his mother was married, to “a brutal man,” but Jacob told his stepfather never to hit him, “‘or I’m going to kill you.’ I said it with a certain amount of conviction.”

After O-levels his mother pressured him to get a job, but he went to live with friends and was put in the scholarship class at school. He couldn’t find work when he left; those were the days of Eric Gairy’s dictatorship, and the school was considered a hotbed of dissent.

Ross took to lying in the road that ran through the village, in despair, reading Walcott and other Caribbean writers, and writing himself, “as a kind of release.” He got a sense of the lives of ordinary Grenadians during that time, he says, especially the women, with whom he’s always empathised. There were few opportunities for poor boys; far fewer for girls, including his own sisters.

But he got out – with unexpected help. “You never know who’s watching you, constructing a narrative about you.” He applied for a job as a hotel waiter, but instead his former headmaster asked him to teach religious instruction. Ross hastily read the Bible and took on a class of girls almost his own age. It was a baptism of fire, he says, but things improved when he began teaching human and social biology, which he’d actually studied. Again, other people were looking out for him, and when a scholarship to France came up, he was nominated, and won it.

He returned to Grenada from the University of Grenoble, taught again, then became director of culture during the Revo. He didn’t always agree with the Bishop government, but became associated with it, and after the American invasion, his family feared for his life.

The Flying Turkey saved him. A calypsonian whose real name was Cecil Belfon, he had put aside money for his own escape, but lent it to Ross, who paid it back after he reached England in 1984.

“There’s this serendipity, chance, magical conflations that have made me what I am today,” he marvels. He still tries to repay these debts, by helping Grenadian writers when he can.

In England he was reunited with a woman he’d met while touring with a Grenadian cultural production, Camaho (the First Peoples’ name for the island, which Ross has used in his fiction). He and Pamela – a Grenadian raised in England – married and had a daughter and a son. Ross, who already had a daughter in Grenada, was besotted with his second baby, and spent a year at home in Harlesden, north London, looking after her while Pamela worked as a telephonist, then became a teacher. Later he packed boxes in a supermarket, but he was driven to become a writer. His wife saw things differently; they separated 20 years ago.

Again friends came to his help. Thanks to Grenadian writer Merle Collins he became editor of an arts magazine; then he taught linguistics and textual analysis at Goldsmiths College, London.

His first book was published shortly after he arrived in England, stories collected by friends who thought he’d died in the US invasion. Those early stories, he says, are the ones Grenadians love the most. Around then, feeling betrayed after the invasion, he also wrote a “massive” manuscript, out of anger and hysteria; he says it was “no good,” but is reworking it.

Ross went freelance after seven years at Goldsmiths, because he couldn’t write and teach at once. He says, rightly, he’s good at teaching, and he taught evening classes, and for the Arvon Foundation. Those were his “rockstone years,” though.

But now he’s been an editor for five years with Peepal Tree Press, Jeremy Poynting’s little company, based in Leeds, where Ross too now lives. It’s given many Caribbean writers their sole chance at being published, and like them, Ross is full of praise for Poynting’s patience, self-sacrifice, and for being “the best editor I’ve ever worked with.” (Both finalists for this year’s OCM Bocas Prize, poetry and fiction – Shara McCallum’s Madwoman and the winner, Jennifer Rahim’s Curfew Chronicles – were Peepal Tree books.)

PHOTO BY MARLON JAMES courtesy the NGC Bocas LitFest.

Ross has edited several anthologies and written two collections of short stories and two novels. The Bone Readers (2017) a crime thriller, is the first of a planned quartet.

His rockstone years are over. His first novel, Pynter Bender, was shortlisted for the 2009 Commonwealth Writers Regional Prize. He’s a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. The Bone Readers won the 2017 Jhalak prize for Book of the Year by a Writer of Colour. Bernadine Evaristo wrote in the UK Guardian: “Jacob Ross…deserves a much wider audience…

“Ross’s characters are always powerfully delineated through brilliant visual descriptions, dialogue that trips off the tongue, and keenly observed behaviour…

“The Bone Readers is a page-turner, but its insights and language are equally testament to a literary novel of impressive depth and acuity.”

Next year, if we’re lucky, he may return to Bocas to teach a workshop on novels. Now, he shoulders his backpack and goes on his way, a watchful, self-contained man, reflecting deeply on “this messy, fractious, uncertain thing we call humanity.”

Comments

"Jacob Ross: Master of his craft"