Design, drama & mas

SHEREEN ALI

Trinidadians love to be dramatic, and play a mas. Some people perform to escape reality, while others perform to engage with it. We use performance for many things, including therapy, art, business, persuasion, and entertainment.

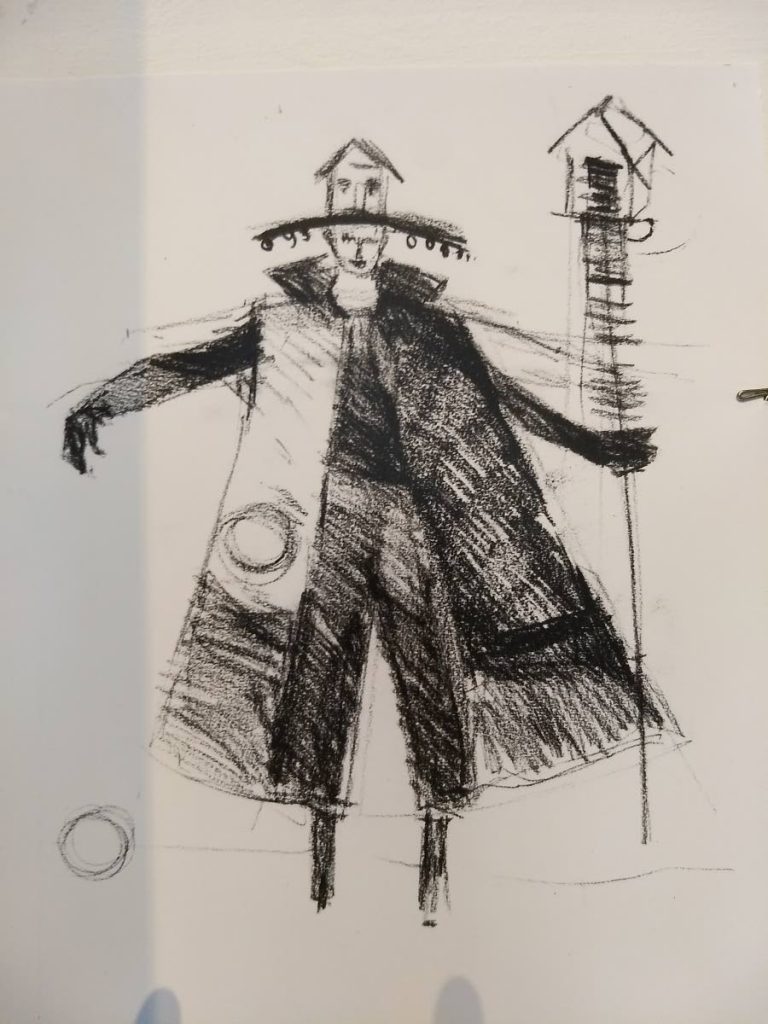

But what makes for a compelling performance at a professional level are the unsung, essential design elements and processes that all come together to make the whole. How you design a set, make a costume, paint an actor’s face or mask, skilfully deploy sound and light and props, and even how you collaborate or quarrel with your fellow team members to create an original performance piece all feed into the quality of the final work.

The recent three-day event Design for Performance TT 2018 shone a light on some of these elements, while also being a staging ground for TT’s ambitious participation at the Prague Quadrennial 2019 (PQ 2019), where theatrical local designers hope to showcase their talents.

Held every four years, the Prague Quadrennial is the world’s largest event in contemporary scenography, which includes costume, stage, lighting, sound design, and theatre architecture for dance, drama, multi-media performances and performance art. The PQ 2019 takes place in Prague, Czechoslovakia next year from June 6-16.

The Design for Performance TT events were presented by the Academy for the Performing Arts (APA) of the University of TT (UTT) in collaboration with the National Drama Association. A programme of this type has not been held since 1990. It included panel discussions and a lively exhibition of beautifully made miniature set designs and full scale theatrical costumes, with work by UTT students as well as design professionals Meiling, Kathryn Chan, Greer Woodham-Jones, Mervyn de Goeas, and others.

Held at NAPA, Port of Spain on March 8, 9 and 10, Thursday’s opening sessions included a live video presentation by associate professor of design Loyce Arthur from the University of Iowa’s College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. Arthur has expertise in costume design, masks and puppetry. She has designed costumes for many US productions, and has studied mask making traditions from cultures including Italy, Ghana, and Bali, as well as researching East Indian Kathakali theatre forms. She has also studied carnival traditions from around the world.

Arthur said she grew up in Grenada playing mas, and she owed her interest in costume design, especially her love of colour, texture and bold design, to the influence of Carnival in her formative years.

She remembered her delight in 1990 when she travelled to Trinidad and saw Carnival here (that was the year of Peter Minshall’s band Red): “I was hooked, I was in heaven. It was a seminal moment which led me down a fruitful and exciting path.”

She went on to outline six key areas in which carnival traditions intersect with theatre design:

(1) visual storytelling;

(2) diverse processes and sources of creative inspiration;

(3) use of basic design elements like shape, balance, space, texture and rhythm;

(4) processes of art making where one must test, refine, re-test, and assess design approaches;

(5) processes of collaboration involving networks of people and sometimes, managing conflicts;

(6) an awareness of the purpose and audience of any performance work – who is it for?

She said that while sources of imagery abound, it is important to avoid cultural appropriation, and to treat any source material used to inspire new designs with sensitivity and respect.

Her comments on collaboration and appropriation triggered spirited contributions from some audience members including theatre designer/director Mervyn de Goeas, who said that Trinidadians have elevated cultural and historical appropriation to an art form. He gave the example of TT Indian masquerade as taking one people’s culture and re-presenting it on the street in a new way. How do we deal with that, if we’re trying to be sensitive, he asked, while noting that many do not even try to be sensitive.

Multimedia artist and performer Rubadiri Victor commented on the use of appropriation in adversarial power relationships as a possible form of resistance or reparation, but noted that “many design things come from sacred spaces,” and that performance artists should respect sources, and ask permissions. He pointed out that mas presentations that borrow from other sources may often transform them and make something different in the process.

Meanwhile, UTT assistant professor in scene design Edwin Erminy, spoke of his inspiration from works by the Cuban novelist Alejo Carpentier who hugely influenced Latin American literature with his Cuban invention of magical realism. Erminy said it is a revolutionary approach, because with it, “we have the potential to create our own reality, and what Europeans categorise as our madness, or our crazy dreaming, is as valid as their version of reality.”

Erminy is an architect from Caracas, Venezuela with a Masters in Art and Design from St Martin’s College in London. He has been a prolific production designer for many performing arts events, as well as corporate fashion and publicity events in Venezuela, Colombia, the US and Trinidad.

He said making theatre from magical realism involves much work with different cultural essences, including some Baroque influences in the Caribbean. He spoke of cultural appropriation in ex-colonies like ours as a kind of “cannibalism”.

“We as oppressed people have been deprived of our memories, of our own stories, so we are continually rebuilding and creating memories. Some of our memories are even made up (because they do not truly correspond to the original source)… So in evoking things, we make up stories that refer to a past that may be mythical… We even use the stories that have been imposed on us by the ruling classes, and we cannibalise them, we eat them, we transform them, we excrete them, and something that is totally different comes out of that process.”

He noted, “That’s the story of South American rhythms: slaves outside heard the waltzes from European ballrooms, then they made versions with their drums and cuatros, and that’s where joropo, samba and many South American rhythms come from, they were appropriated by the enslaved peoples and transformed into their own language. That’s the story of jazz, right?”

He said perspective sees cultural cannibalism as something to be encouraged – that colonised people do not need to respect the sacredness of the culture of the people who colonised them.

He said another perspective sees all Caribbean identities as fluid: we are people surrounded by water, and our identities are not set in stone like, say, the Germanic identity. Rather, he said, our identities were stolen from us, so our identities are constantly a project in construction. That allows us to have a cultural dialogue between different essences, and he celebrated the idea that people from different heritages can complete each other’s stories in this space – something he presumed could only happen here in the New World. He said, “That allows us a great opportunity as Caribbean people to extend bridges and open doors.”

Comments

"Design, drama & mas"