Bowen's Stories

Onb my second day in Trinidad, back in 2013, a friend took me to a party on Sydenham Avenue, St Ann's.

“It's at the artist Eddie Bowen's house,” she told me. “It'll be fun.”

It was fun, and raucous. The house/studio/gallery was full of people I would come to recognise as members of Trinidad’s arts scene. Bowen wandered around pouring drinks, entertaining guests with a permanent grin on his face, attempting to roll a cigarette in a banana leaf.

Paintings were everywhere: hanging or stacked up against walls, including the rooms upstairs that Bowen rented to writers and film-makers. Some of us drove around the corner to a rival party, ate all the food and came back to carry on drinking.

So, this is Trinidad, I thought.

In hindsight, the party marked the end of an era. Bowen sold the house soon after and dismantled it to use the wood to build another. Some artists moved away. The next generation appear somewhat reticent.

But Bowen is back. His show Stories opened last week at Y Gallery. They’re large works – mostly richly-concocted, hallucinatory landscapes.

His life hasn't been easy over the last few years. But rather than emotion in the paintings, I find ceaseless experimentation, as though he can paint away life's struggles.

“Under each of these are three or four ideas that got painted over,” he says.

Looking at the winding path, patchwork hills and spindly pastel-pink trees on a piece called North Coast Road, I wonder if he begins by painting specific objects he's looking at.

“I always start by completely emptying my mind,” he says.

The previous night, a midweek evening in semi-deserted Woodbrook, he seemed strident, less concerned with political correctness.

“I'm not a martyr to no cause,” he tells me, as we sip beers. “I'm really not that interested in very much.

“In England, I was always some kind of alien. When I came back to Trinidad I felt even more like that, and I still do. I belong here, yeah, my family's 250 years here, at a certain level of wealth and privilege, but that's never really worked for me... After art school, Brixton, riots, Mrs Thatcher, coming back was like coming back to a village.”

He tells me about his childhood as one of seven siblings and about his father, a World War II veteran who, in his 50s, married his mother, an 18-year-old maid of “Venezuelan Carib/First People ancestry.” He talks about being sent to boarding school in England, where he chose art over a promising career as an opening batsman.

“I used to play best when I had a hangover,” he says. “Because I wasn't so self-conscious and I didn't care, and this red ball coming at me was something to be put aside or hit very hard. But the rest of the time, I was thinking too much about it.”

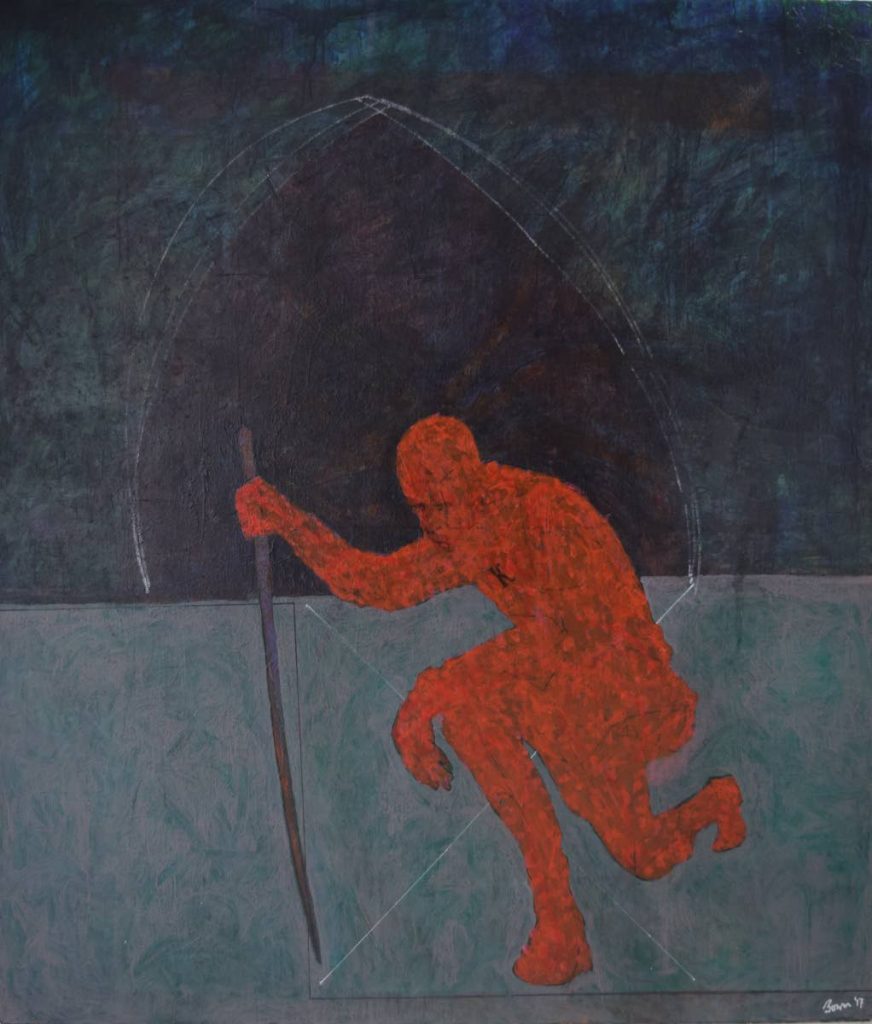

There's little in his work to suggest a love of sport but the standout piece, Kneel, is, at least in part, about a sportsman.

“It's to do with (Colin) Kaepernick. He struck a chord with me when he did that,” he says of the San Francisco 49ers quarterback who began the US anthem protests at NFL games. “But it's not just about that.”

The scarlet-red male figure, bent on one knee holding a sword to the earth, is stark against a murky background. Behind him, a shadowy, geometrically-drawn cathedral-like dome looms, exerting an imperceptible force.

“I was a heavy Catholic,” he confesses. “Which involves a lot of kneeling. I was very religious at one point.”

What got that out of you? I ask

“Yoga,” he deadpans. “One day I told my girlfriend 'I'm giving something up for Lent.' She asked what. I said, 'Catholicism.'

“But Kneel is also about 'painting' things,” he says, pointing out the “horizontal junctions” and “compositional” elements.

So, why has he gone back to painting big work?

“I went and bought five grand worth of paint and some canvases, put them in the house in Sans Souci and thought to myself, 'I'm in my late 40s, early 50s, if I don't get on with it right now and have some faith and optimism,'... I thought I'd lost that. Life and all the trippy stuff kind of erodes your confidence.

“I thought, let me go back to that and override this kind of mock politeness. I had geared down to deal with everyday matters. I had a son to look after. My discipline had been eroded by a divorce, family matters, and all of a sudden it was free because the environment I was locked into was gone… I thought about what I really love and why I came back to Trinidad in the first place.”

From 1972- 1985, Bowen attended school in Surrey, just outside London. He was headbutted in the street one day by skinheads who called him the n-word and he thought his parents were crazy for moving from a house on Lady Chancellor Road to a “semi-detached in Croydon.”

Destined to read English at university, one day Bowen asked his teacher if he could skip physics for the art room. Amazed at being granted the request, he set about becoming an artist. Day trips to London's galleries were followed by art school.

But afterwards, a lecturer told him, “Don't stay in England, get out of the North, go to the South… Go where the magic realism is, where the heat is. Celebrate your home. If you stay in London you have to be young, gay or Jewish to get into the art world.”

Whether that was true then or now, Bowen's coming home may well have made him the experimental artist that he is.

I ask if he misses London.

“Very much,” he says instantly, and repeats it.

“Here is a mental laboratory,” he says about life in Trinidad.

I wonder, silently, if he means this in a good or bad way. But, for once, Eddie Bowen gives little away.

Stories is on until December 2 at Y Gallery. Woodbrook.

Comments

"Bowen’s Stories"